"For 130 years, workers around the world celebrated May Day.They did so in times and places where that was incredibly difficult, where dicatorial regimes banned their actions, where employers and their thugs used violence against them.Nothing could stop us from having our day, the day workers everywhere can call our own.Nothing -- until COVID-19 came along.Today, hundreds of millions of us are unable to go to our regular workplaces. Our frontline workers take enormous risks every day. The global economy is in free-fall and never before were our unions needed more than they are now.May Day 2020 must go ahead, and if we can't meet in the streets, we'll meet online.Tomorrow, Friday, LabourStart in partnership with global unions is going live with a 12 hour broadcast on the net.We have everything you'd expect from a May Day celebration.The leaders of global, national and local unions will deliver their May Day addresses.Individual workers and activists will talk about their struggles.We'll show historical footage of May Day in the past in places like London and Istanbul.And we'll have music -- lots of music. In fact, we're participating in a global solidarity concert as part of the celebration.I'd like to invite you to do two things this May Day:1. Join us from 07:00 UTC (08:00 in London) until 19:00 here:2. Make sure that other members of your union -- and the general public too -- know about this historic event. Spread the word!Thank you -- and see you on May Day!Eric LeeLabourStart"

30.4.20

May Day

We might not be able to march or parade but:

29.4.20

Edwin Morgan: remembering Scotland's first poet laureate at 100

James McGonigal, University of Glasgow

Grey over Riddrie the clouds piled up,

dragged their rain through the cemetery trees.

The gates shone cold. Wind rose

flaring the hissing leaves, the branches

swung, heavy, across the lamps.

From King Billy (1963)

Why do we remember particular poems and poets – and happily forget others? The Scottish poet Edwin Morgan was born 100 years ago, and this week marks the the start of a year of celebration of the man and his work. It goes ahead in a virtual way, with public events cancelled in days of lockdown or deferred to 2021 – an advantage of a year-long celebration.

Born in Glasgow on April 27, 1920, Edwin George Morgan led a remarkable and wide-ranging creative life. He published 25 collections of his own poetry and translated hundreds of Russian, Hungarian, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French and German poems too. He also wrote plays, opera libretti, radio broadcasts, journalism, book and drama reviews and literary criticism.

His work continues to be published, produced, taught and celebrated. His poetry is memorable not only for Glasgow, his native city, and for Scotland – but for a wider audience thanks to Morgan’s lifelong concern with universal and cosmic matters.

Glasgow and Scotland

Morgan loved the city of his birth for its energy, industrial inventiveness, humour and crowded streets. He warmed to its humanity, shared its sorrows, wrote against scarring deprivation, recovered its history (real and imagined), and projected several Glasgows into the future.

He celebrated its changing cityscape in The Starlings in George Square, and its interactive street culture in Trio, where we encounter three Glaswegians bearing Christmas gifts of a guitar festooned with mistletoe, a new baby and a chihuahua, cosy in a tartan coat. He recorded the darker elements of Glasgow too, such as the city’s sectarian violence and notorious tribal gang culture in King Billy.

The directness of these interactions is carried in authentic urban speech rhythms new to Scottish poetry at the time. In the Snack-bar and Death in Duke Street vividly describe the long deprivation and the sudden death that are also part of the scene:

Only the hungry ambulance

howls for him through the staring squares.

Morgan taught English at Glasgow University all his working life, and became the city’s first poet laureate in 1999. He became Scotland’s laureate too, in 2004 – its first “makar” or national poet. He celebrated Scotland’s varied landscapes, people and places, whether humorously in Canedolia, or reflectively in Sonnets from Scotland.

For Morgan, part of a poet’s job was to remind Scots that if they want to achieve something in the world and to really be taken seriously, then they need to find words to show the world what they stand for. Poets and other writers can help them to do this. When Scotland’s ambitious new parliament building opened at Holyrood at the foot of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, he wrote:

What do the people want of the place? They want it to be filled with thinking

persons as open and adventurous as its architecture.

A nest of fearties is what they do not want.

A symposium of procrastinators is what they do not want.

A phalanx of forelock-tuggers is what they do not want.

And perhaps above all the droopy mantra of “it wizny me” is what they do not want.

Lines from For the Opening of the Scottish Parliament, October 9 2004

The world, the universe and love

Morgan travelled widely – to Africa and the Middle East during the second world war, to Russia and Eastern Europe during the Cold War, to the US, New Zealand and the North Pole. These are the places he writes of in his poetry. The New Divan is his mysterious war poem in which he records in 100 sharp filmic stanzas, memories from the second world war desert campaign that shift like characters in an Arabian Nights tale – and yet are modern soldiers and lovers too.

Space and time travel fascinated him. A supersonic flight by Concorde to Lapland was the nearest he could actually get to outer space, where he had often journeyed in his imagination. The First Men on Mercury dramatises a linguistic encounter between Western astronauts and Mercurian beings that ends in a complete and hilarious transposition of language and power. Morgan believed that humanity would ultimately endeavour to create “A Home in Space”, which is the title of another poem that follows “a band of tranquil defiers” who decide to cut off all connection with the Earth.

This was a poet who could speak as a space module or a Mercurian, and also as an apple, a computer, an Egyptian mummy. He was an acrobat of words and identities. Perhaps his own identity as a gay man, risking censure or imprisonment through most of his life, encouraged that ability to shape-shift. His love poems are haunting. Some deal with loss or transience, as in One Cigarette, or Absence, or Dear man, my love goes out in waves, or with the physical risks of a forbidden lifestyle, as in Glasgow Green or Christmas Eve, which tells of a fleeting encounter with another man on a bus.

But his poems also celebrate ways in which all lovers share the tender details of everyday life together, as in Strawberries. His writing of gay and queer experience had a significant impact on social attitudes and political change in Scotland. His voice spoke for many young or isolated gay people, with an advocacy that was subtle but powerful in effect.

Collaboration

Morgan was an individualist, in some senses a loner. And yet he was also an inspirer of creative partnerships – in art, photography, opera, music and drama, cultural journalism and poetry in performance. His early support was invaluable to an array of groundbreaking poets and artists such as Ian Hamilton Finlay, Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead and Jackie Kay, and he enjoyed collaborations with Scots musicians such as jazz saxophonist Tommy Smith and indie band Idlewild.

Such lists could be extended. They continue to grow through the Edwin Morgan Trust, set up to administer his cultural legacy by supporting new poets and poetry in Scotland and Europe as well as wider artistic responses to Morgan’s work. There are centenary publications too with new collections of selected poems and prose. For those who loved this quiet man of Scottish poetry it promises to be a memorable year.

James McGonigal, Emeritus Professor of English in Education, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

24.4.20

Artist Timothy Leeson's rabbit for Madison

WEIRD UK NEWS: A red squirrel is pictured panic buying. 9. Warning not to use 'dangerous' sky lanterns to support NHS. 10. MoneySavingExpert ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

23.4.20

Shakespeare on Zoom

Shakespeare on Zoom: how a theatre group in isolation conjured up a Tempest

Madeleine MacMahon as ‘Sebastianne’ in a live production of The Tempest by Creation Theatre from 2019.

Creation Theatre/ Big Telly Theatre Company

While theatres remain closed, the way we watch Shakespeare is changing. When I picture the audiences Shakespeare would have written for, I think of the groundlings in Shakespeare in Love(1998). They stand, arms on the edges of the stage, staring upwards, eyes filled with tears – laughing, clapping, gasping. They are part of the show – and they show that they’re there. In the bright afternoon sun, the actors can see and hear every reaction.

Right now, of course, it’s not possible to take a trip to the playhouse. Still, with the National Theatre, the Globe, and the Really Useful Group moving quickly to put past performances online, the theatre can come to us via YouTube. We can see and hear the actors (and, having watched Hamlet, Jane Eyre and The Phantom of the Opera, I’ve been very grateful for it). But even though we can tweet our reactions, the actors can’t see or hear us.

The possibility of live performances during lockdown might change that. Over the Easter weekend, I watched an Oxford-based theatre company, Creation Theatre, and their co-producers at Big Telly Theatre Company from Portstewart in Northern Ireland, put on a production of The Tempest via video conferencing platform Zoom.

It seemed a tricky challenge under lockdown, with each cast member performing (and rehearsing) from home. Indeed, as chief executive and creative producer Lucy Askew warned before the play began, the night’s events were at the mercy of the technological gods.

But, when the play began and Ariel conjured a storm, suddenly it became clear that – despite our isolation – we too were part of the action. The audience’s microphones (muted while the actors spoke) were suddenly raised and we were asked to click our fingers to make it rain. The screen was full of audience members – and their pets, and their glasses of wine, and their pyjamas – and the storm was, even if I say so myself, convincing.

Within the space of an hour, the audience asked Antonio for answers via the chat function as he boasted of his usurpation of Prospero, we blew wind into the path of his ship and – in lieu of a banquet – all held up an offering of snacks (chocolate biscuits, from me). Each time other audience members appeared on screen, there was a rush of excitement as we got to see one another.

Listening to the island.

Shakespeare knew the importance of his audience’s reaction. At the end of The Tempest, Prospero relinquishes his magic and asks for something in return:

But release me from my bandsWith the help of your good hands.Gentle breath of yours my sailsMust fill, or else my project fails.

It’s a moment when we are asked to make some noise – to clap with our “good hands”, to cheer (or whistle, or shout) with our “gentle breath”. Prospero’s redemption, if we allow him that possibility, comes from finally turning outwards, it comes from him seeing the necessity of his connection to others – to his daughter, to his once-forgotten subjects in Milan, and, perhaps, to us.

Yet, for all of the noise we made, this new medium exposed the myriad kinds of loneliness in The Tempest. Prospero sat in front of a backdrop of television screens, reminding us that we were all at one remove from one another. When Caliban described the noises of the island, the “Sounds, and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not”, it was painfully apparent that he was alone and that there was nothing real to hear. When Ferdinand proposed to Miranda and reached from his screen to hers in an impressive feat of Zoom technology, that brief moment of “contact” was bittersweet.

After all, the despair of being alone is a fear which Prospero seeks to create. As ordered, Ariel deliberately scatters the shipwrecked courtiers across the island. Yet, as John Donne, a contemporary of Shakespeare, wrote:

No man is an island entire of itself;every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

The dispersed groups come back together – Prospero leaves his island exile, and returns home. It’s not a perfect resolution, and it’s not a happy ending, but it is, nonetheless, a reunion.

Somewhere new?

As site-specific, conference call plays go, The Tempest lends itself to such a production. It’s a play about isolation and exile, about characters moving around a small island without ever meeting one another. Creation’s performance did nothing to disguise its new medium. In fact, the most powerful part of the performance came as Prospero spoke the famous epilogue which begins: “Now my charms are all o’erthrown”.

The cast slowly and methodically packed up their bedsheet green screens and wiped off their makeup. They changed their onscreen identities from their character’s names back to their own. By the time we were invited to stay on Zoom for a moment or two, to catch up with friends, thank the actors, and wave goodbye, the spell was broken.

But the magic may not be entirely over, not least as the popularity of their performances have led to Creation extending its run. Moreover, The Tempest is not the only play offered in this new genre of “Zoom Shakespeare”. Another group of actors recently collaborated to create A Midsummer Night’s Stream, which they advertise not simply as a reading but a live performance, “adapted for our stage”. And there is no reason to think that “Zoom Theatre” will stick to Shakespeare.

While we will (to entirely misuse one of Prospero’s lines) return to a time when we “have no screen between this part he play’d/And him he play’d it for”, Zoom Theatre may not be a temporary measure. Perhaps new plays will be written with the possibilities of Zoom and YouTube in mind. For many, watching theatre from home will allow for greater access and comfort. And, for now, speaking back, making noise, and waving at strangers, could inject a bit of silliness into our own isolated worlds.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

21.4.20

Open Call | Thamesmead Open Art Commission, UK

The Thamesmead Open invites artists to react to the unique setting of Thamesmead with proposals that directly respond to the location and encourage ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

19.4.20

The age of stability is over, and coronavirus is just the beginning

Troutnut / shutterstock

Humanity has only recently become accustomed to a stable climate. For most of its history, long ice ages punctuated with hot spells alternated with short warm periods. Transitions from cold to warm climates were especially chaotic.

Then, about 10,000 years ago, the Earth suddenly entered into a period of climate stability modern humans had never seen before. But thanks to ever accelerating emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, humanity is now bringing this period to an end.

This loss of stability could be disastrous. If the coronavirus pandemic can teach us anything about the climate crisis it is this: our modern interconnected global economy is much more vulnerable than we thought, and we must urgently become more resilient and better prepared for the unknown.

After all, a stable climate underpins much of modern civilisation. About half of humanity depends on stable monsoon rains for food production. Many agricultural plants need certain temperature variations within a year to produce a stable crop, and heat stress can damage them greatly. We rely on intact glaciers or healthy forest soils to store water for the dry season. Heavy rains and storms can wipe out the infrastructure of whole regions.

These are the sorts of climate impacts that we know about, and have been extensively studied by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). But the biggest risk may yet come from climate-related chaos that we did not expect.

Impossible heatwaves – in consecutive years

In 2018, a prolonged heat wave and drought hit much of western and northern Europe and decimated much of the potato harvest in the region. Temperatures in my native Germany reached record highs in a summer that was drier and hotter than in many parts of the Mediterranean. Climate models had predicted Europe’s most extreme heat increases would occur in Greece, Turkey and Ukraine, so the odds of such a heatwave seemed impossibly low.

Only one year on, in 2019, western Europe was struck by another “impossible” heat wave. In Germany, with temperatures topping 40°C, the record of the previous year was broken twice. Even in the Netherlands, known for its cool sea breeze even at peak summer, peak temperatures exceeded a searing 39°C.

Huge wildfires arrived decades early

A large part of Australia’s forests are concentrated in the south-east of the country. This valuable ecosystem evolved with fire and thus is supposed to burn frequently. In these natural fires, typically 1-2% of the area is consumed by flames.

Wildfire and climate models – including one I worked on myself – did predict a large increase in bushfire activity in the forests of south-east Australia. But they predicted this would happen towards the end of this century. The models certainly did not foresee that megafires wiping out as much as 20% of these forests would strike as early as 2020.

Locusts are a climate crisis

In the long term, the IPCC predicts crop yields will decrease by around 10% or more, but to date it has ignored the possibility of large-scale pest outbreaks, which can wipe out entire harvests.

At the end of 2019 and beginning of 2020, the Arabian peninsula experienced much wetter weather than normal, likely owed to ocean warming. This created conditions that enabled numbers of desert locusts to explode.

This unusual event was followed by another, a storm that shifted most of this locust army, now several hundred billion strong, to East Africa. In Kenya, it became the worst such outbreak for more than 70 years. With the rainy season just arrived and seeds sown for the next cropping season, it is now feared that continued breeding of the locusts will create a second wave that will be far worse than the first one.

Read more:

Climate scientists tend to focus on slow changes with their climate predictions. But how much the weather becomes more chaotic is notoriously difficult to predict with climate models. We also have only a very superficial understanding of how vulnerable our modern society is to climate chaos and unexpected climate-related events.

Instead of seeing the climate problem as one felt by the next generations, we need to start focusing on what could happen tomorrow, or next year. To do that, we must better understand, appreciate and acknowledge the vulnerability of modern society – and address this vulnerability at its core.

Wolfgang Knorr, Senior Research Scientist, Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, Lund University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

16.4.20

GET OFF YER ARSE

Lockdown is producing some great ways to show art and an ARTZINE called GET OFF YER ARSE is one of them.

Available online to download for FREE, Get Off Yer Arse is a well designed zine in pdf format that’s been put together by the artist Greta Sharp, and she says:

“GET OFF YER ARSE is a DIY online publication sharing artists’ work that explore issues around mental health during a period of self-isolation and social distancing during the 2020 lockdown...

...I’ve always had ideas of creating a zine, and when a few weeks ago the entire world went into a state of emergency, (and what has unfolded since is something that was unimaginable to all of us) it seemed like an apt time to bring many creatives together on a digital platform.”

15.4.20

Banksy reveals new graffiti as he 'works from home' during coronavirus lockdown

Due to the UK being in lockdown amid the coronavirus pandemic, the artist has been forced, like many others, to work from home. Ad. His latest graffiti, ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

12.4.20

Artist creates colouring pages for Easter to thank key workers

... Loudwater Mill, Station Road, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire. HP10 9TY | 01676637 | Registered in England & Wales. Worcester News. News.

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

9.4.20

Families across Leicester helping researchers discover the difference art can make to children

Funded by Arts Council England, it teams academic researchers from De Montfort University Leicester (DMU) with families with a child under one and ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

6.4.20

A Tate Retrospective Tamed the Radicalism of William Blake

³ Here is where Blake's Britain most closely resembles the UK today, and the ... A brief synopsis of his activism and art will be instructive here. ... 16, 2017, ft.com; Will Hutton, “The bad news is we're dying early in Britain—and it's all ...

* The full article is published here...

You may also be interested in this article.

* The full article is published here...

You may also be interested in this article.

3.4.20

Local historian unearths valuable Georgian painting by matching it to single-line description in old ...

Mr Mould, an acclaimed British art expert, is known for his skill in unearthing 'sleeper' paintings - works whose real value has been overlooked. He ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

1.4.20

The importance of art in the time of coronavirus

The author in Nairobi as part of a research project in 2019 into art and community health.

Photo by Georges Mboya, Author provided

Louis Netter, University of Portsmouth

People are dying, critical resources are stretched, the very essence of our freedom is shrinking – and yet we are moved inward, to the vast inner space of our thoughts and imagination, a place we have perhaps neglected. Of all the necessities we now feel so keenly aware of, the arts and their contribution to our wellbeing is evident and, in some ways, central to coronavirus confinement for those of us locked in at home. For some, there are more pressing needs. But momentary joys, even in dire circumstances, often come through the arts and collective expression.

As a lecturer in illustration, I am constantly encouraging students to find an artistic voice and identify, in this crowded world of images, some touchstones to develop their own aesthetic. Art critic and theorist John Berger identified, in the act of drawing, something that is inherently autobiographical – a continual process of refining vision which moves us towards new understandings about ourselves and the world around us.

In this time of crisis and isolation, the role of art becomes more central to our lives, whether we realise it or not. We can easily take for granted the grand buffet of media that is available to us – and I can be guilty of a lack patience when students find it difficult discerning quality amid a sea of memes and amateur artistic indulgence which, to the unsuspecting, can appear to be worthy. The lack of curation on the internet frustrates people like me who value culture and its contribution and equally, are quickly becoming grumpy old men and women.

Whether we like it or not our consumption habits – including media – form who we are, our values, our inclinations. They are a patchwork of beliefs that are also tested in these difficult times.

Art can set you free

I was a high school teacher in Sleepy Hollow, New York, 20 miles away from ground zero when the 9/11 attacks happened. It was a time like now that tested our collective ability to make sense of a new normal and to mourn for the time before that would never come back. A schism in the collective consciousness that everyone struggled to frame, even artists.

Art Speigelman’s graphic novel In The Shadow of No Towers was less of a coherent narrative about 9/11 than an attempt to reassemble his own psyche through the comfort of his own creations and the medium of the comic itself.

A graphic artist’s way of making sense of 9/11.

Amazon

People on social media are sharing favourite Netflix playlists, songs, videos and even artwork to reach out beyond isolation and share what they love. It is naive to think that such lists are mere casual swaps of entertainment enjoyed and recommended. They are an externalisation of the personality of the list maker: the romance enthusiast, the lover of comedies, the thrill seeker, the horror fan, and the aficionado of obscure documentaries.

Read more:

Coronavirus: five musicals chosen by a musicologist to keep you going during lockdown

In this time of restriction, TV, film, books and video games offer us a chance to be mobile. To move around freely in a fictional world in a way that is now impossible in reality. Art connects us to the foreign, the exotic and the impossible – but in our current context, it also connects us to a world where anything is possible. A world out of our grasp for now.

The world we wake up in is a counterfeit reality. Things look the same. Unlike those now familiar films, the descent of humanity is not apparent in the slow shuffle of moaning, glassy-eyed zombies. The threat we face feels like those clever horror movies like The Blair Witch Project, Paranormal Activity and more recent films like The Quiet Place where we rarely see the source of horror. The current moment is best understood as a kind of low hum of anxiety, like the buzzing of a pylon in a field.

The world that was, the world that is

In my travels to Kenya in 2019 and more specifically Nairobi, I drew regularly. I was working on the Tupumue research project, measuring the lung capacity of 2,600 children aged between five and 18 from two areas in Nairobi: the informal settlement Mukuru and the adjacent affluent area Buruburu.

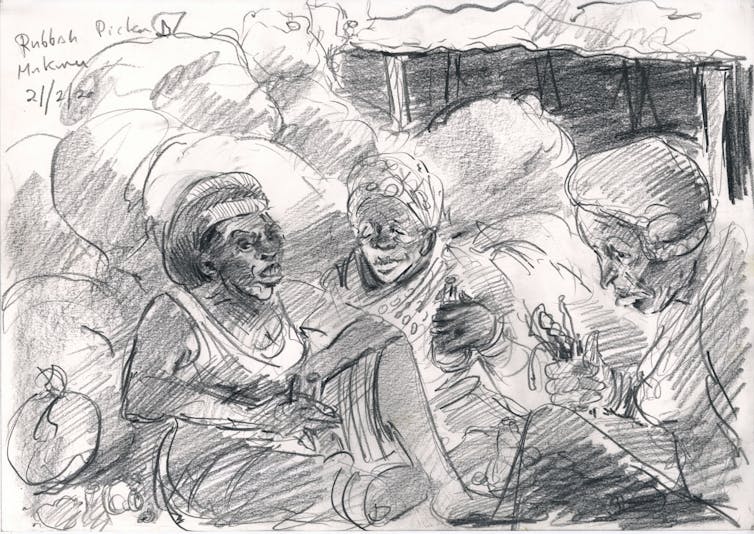

Woman in Mukuru, Nairobi.

Louis Netter

The research team was collaborating with local artists, teachers and community members to develop participatory creative methods to engage with the two communities in the study. The drawings capture my impressions of the vibrant streets of Nairobi and specifically of Mukuru, a large informal settlement, is a visceral flood to the senses.

Women picking through rubbish, Mukuru, Nairobi.

Louis Netter

During an event in which we moved through Mukuru in procession, testing our creative methods for sensitisation which included puppetry, art making (including graffiti), song and dance, a colleague, surveying the crowds of children and people in the narrow, dusty roads, said: “I wouldn’t want to see what a virus would do to this population.”

Man burning electrical wire, Mukuru, Nairobi.

Louis Netter

We are now seeing this unfold and I worry for all of those people living in such close proximity. Self-isolation and the sharing of Netflix lists is an absurd luxury to the people here who live confined in small, steel shacks. Life was hard before COVID-19. After, it could be unbearable.

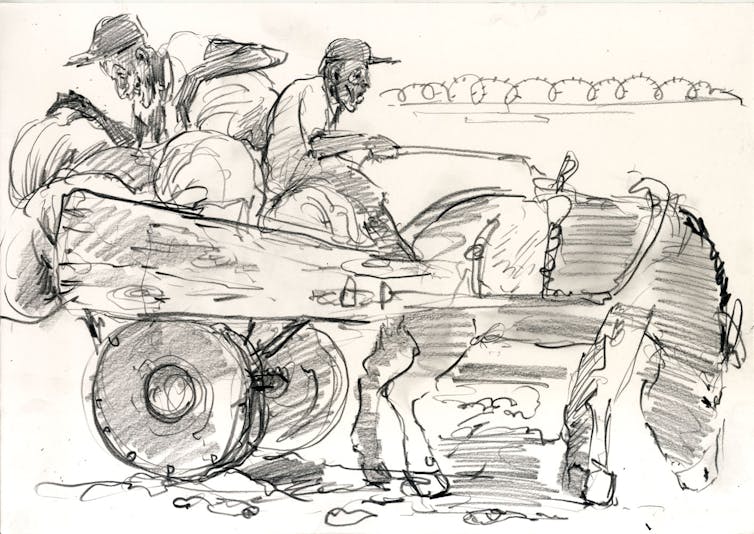

Donkey cart, Buru Buru, Nairobi .

Louis Netter

A life in isolation is nothing new, communities like this have been isolated and invisible to the vast majority of the world for a long time. It is capitalism’s dustbin. When capitalism coughs, these communities perish.

Read more:

Why Africa's journalists aren't doing a good job on COVID-19

So what of the arts in isolation? It might be too early to write that book and paint that picture that captures the buzz of anxiety we all feel. We probably need more time and artists need more sunrises and sunsets to rise and fall on the full, nervous houses. They need more time to listen to the sounds of life interrupted and to mourn for the “world that was”, watching it drift further into the shadows.

Louis Netter, Senior Lecturer in Illustration, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

"Art should be for everyone" – Mari Katayama | Tate

Artist Mari Katayama creates hand-sewn sculptures and photographs that prompt conversations and challenge misconceptions about our bodies. B...