20.12.21

Who was Elsie Inglis?

View on YouTube

16.12.21

Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Rooms at Tate Modern

View on YouTube

5.12.21

Dennis the Menace lives on

Dennis the Menace lives on: the influence of this 70-year-old on everything from darts to raves

The current Somerset House exhibition in London, Beano: The Art of Breaking the Rules, revels in the joyful impudence of the 83-year-old comic magazine’s characters. A tribute to the publication’s impact seems long overdue; as curator Andy Holden says: “Beano’s irreverent sensibility is something that appeals to you as a child, but also, for some, never leaves you.”

The Beano plays an important role in children’s lives because, along with other Beano readers, you become part of a community, through the readers’ letters page, fan art and fan club.

Beano’s longevity can be attributed to what educator Carol Tilley calls the “participatory culture” of comics and its diversity of characters.

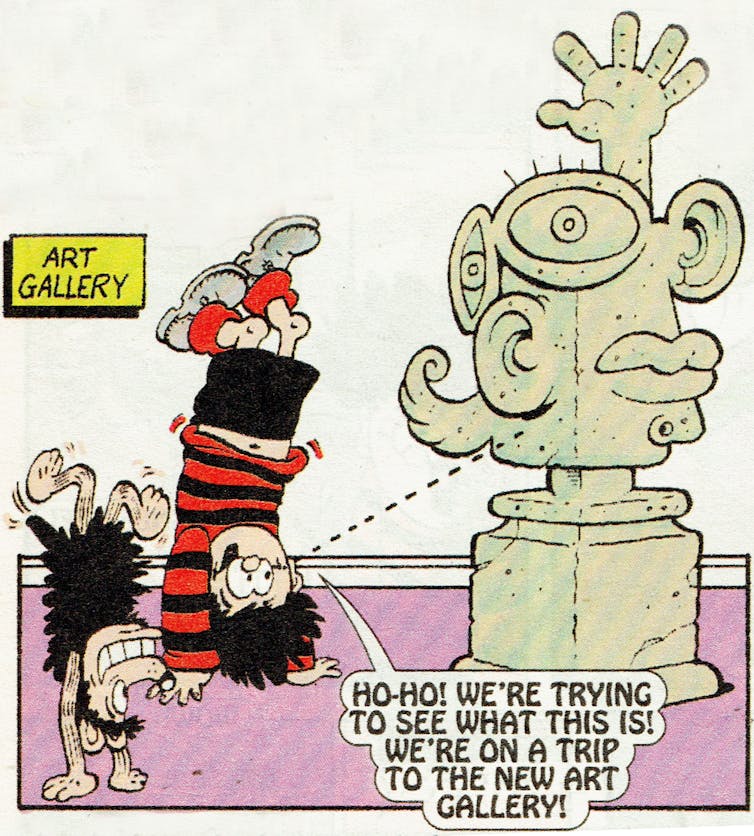

Of all the Beano’s characters, no one better exemplifies the essence of sheer impertinence and anarchic subversiveness - as represented in the exhibition’s title - than Dennis the Menace himself.

Indeed, the 70-year-old character has helped maintain the Beano as a long-running publication. Dennis debuted in a black-and-white half-pager tucked inside the issue of March 17 1951. From that pivotal moment, growing demand for Dennis’s adventures “led him to the colour back cover in 1954 … and then to the cover replacing Biffo the Bear”.

I first discovered Dennis when he was 20 years old, and I was all of eight. In December 1971, I was growing up in Quebec, Canada, and my UK grandparents sent me the 1972 Beano Book as a Christmas present. Dennis was introduced as a large red and black drawing that depicted him shaving his name into his dog Gnasher’s fur. As Beano characters often do, Dennis broke the fourth wall, gazing beyond the page. I immediately identified with this cheeky chap.

Cultural impact

Journalist David Mapstone observes that, until recently, the UK’s weekly printed comics, such as Beano and Dandy (among others), were “a massive influence on the lives of children for decades … and then they were gone. All apart from the best - the Beano - still read weekly by thousands”.

Dennis the Menace’s influence on culture in the past is undeniable, from raves to professional darts, to RuPaul’s Drag Race.

However, today’s Dennis (formerly the Menace) appears more influenced by society rather than the other way around. For instance, he wears new trainers instead of old boots, and he’s addicted to the internet rather than bent on disturbing lines of communication.

Those original themes of subversion appealed to young readers; Dennis would try to fight the law, but the law would generally win – a timeless lesson that can almost be considered a sort of delinquent rite of passage. Dennis’s charm lay in being “an anarchic figure” who expressed others’ feelings of rebellion vicariously through him.

Cartoonist David Law was the artist behind the character’s adventures from 1951 until 1970.

I don’t think the two Dennis stories in my 1972 Beano Book were drawn by Law, but the team that took over from him when he died. Law’s original Dennis the Menace, on the other hand, presented a comparatively raw, crude, and proto-punk aesthetic: irreverance, nihilism and amateurism.

There are visual links between this chaotic Dennis the Menace and the UK’s Viz comic, which began as a do-it-yourself fanzine in 1979.

In researching this article, I rang up Viz co-editor Graham Dury and we talked about the influence that Beano, and Dennis the Menace specifically, had on the comics scene in the UK, and Viz in particular. Beano and Dandy were a major influence on the wonderfully rude and crude Viz, which even satirised some of its characters, Dury told me.

Tumbling into the 21st century

Dennis’s anarchist appeal is not what it used to be; in fact, he is not even featured on the cover of a recent issue of Beano (week of November 27 2021). He does appear in a two-page story, but he is an ally (rather than a menace) to his family, who all work together to escape to a world “unspoiled by internet and mobile phones”. Contrast this with Dennis’s first adventure in 1951, where we are introduced to a very different relationship: Dennis wants to be free to play on the grass and climb trees. Dennis’s dad, meanwhile, decides to control the cheeky chap by tying a dog’s leash around his neck.

The art of breaking the rules is, apparently, knowing what the limits are.

![]()

Julian Lawrence, Senior Lecturer in Comics and Graphic Novels, Teesside University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

3.12.21

Ray Harryhausen | Titan of Cinema (with Natalie Haynes)

View on YouTube

28.11.21

26.11.21

R.B. Kitaj's painting of The Wedding

View on YouTube

24.11.21

An artist and a writer visited the English seaside during the pandemic

– this is what they found

Unfurling along the sandy border between town and beach, the English seaside is a place of contradictions – rich and poor, old and new, fun and desperate. Although many of us have a sugary vision of coastal England as tacky entertainment and a bygone refuge from working life, the reality is that many seaside towns are on the front line of contemporary social, economic and political challenges.

Indeed, despite the recent boost to British seaside resorts provided by pandemic-related travel restrictions, since the 1970s there has been a steady decline in the number of people heading to England’s beaches for their holidays – instead favouring cheap deals overseas.

Austerity policies have also hit a lot of coastal towns hard. And many seaside resorts often have a low life expectancy and high concentrations of chronic disease.

In many places, disgruntlement about such problems may have helped to fuel Brexit. Analysis of the EU referendum by Chris Hanretty, professor of politics, at Royal Holloway, University of London, shows that around 100 of the 120 or so constituencies with a coastline voted to leave. While a poll carried out just ahead of the vote by researchers at the University of Aberdeen suggested that 92% of the fishing industry would be voting to leave the EU.

And for all the increases in visitors once restrictions lifted, many seaside towns have really suffered during the pandemic – with many coastal resorts experiencing surging unemployment rates.

The coast must also contend with the grim consequences of the climate breakdown. With rising sea levels comes the increased risk of flooding and in some instances cliff erosion has led to entire buildings falling into the sea.

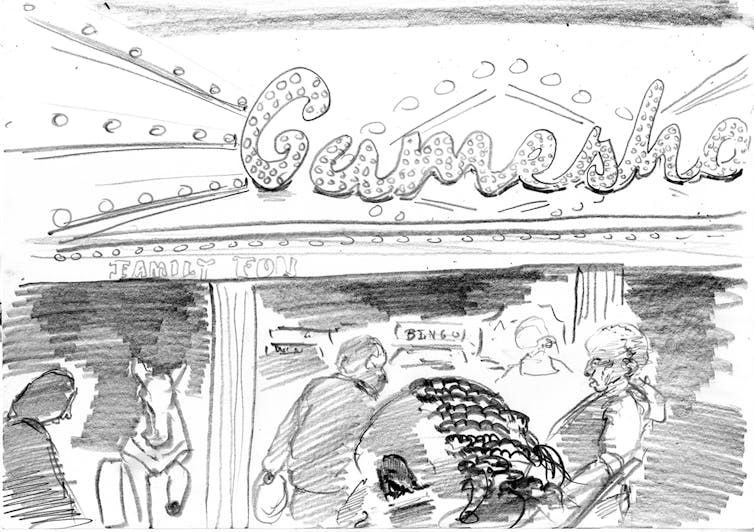

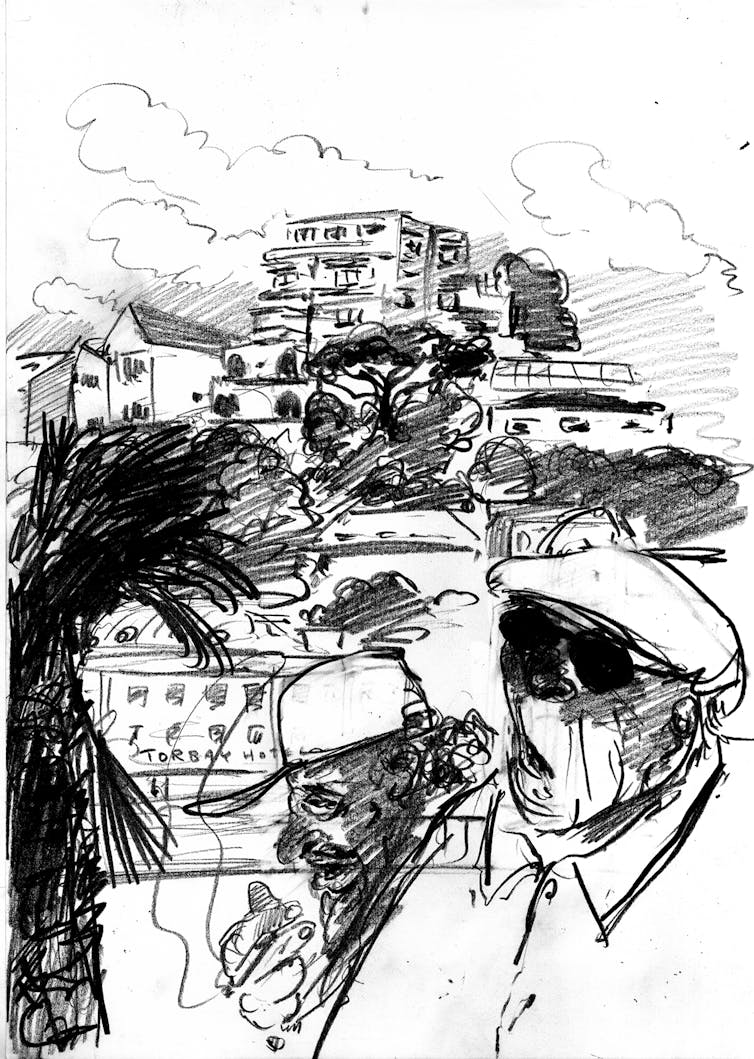

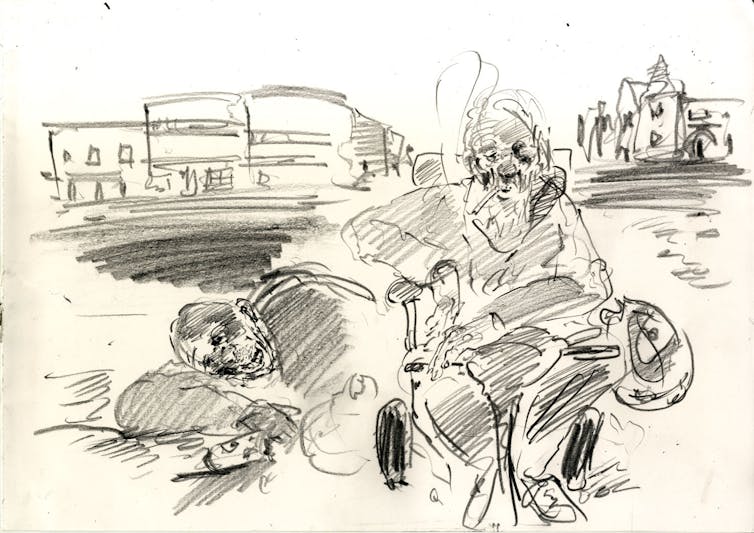

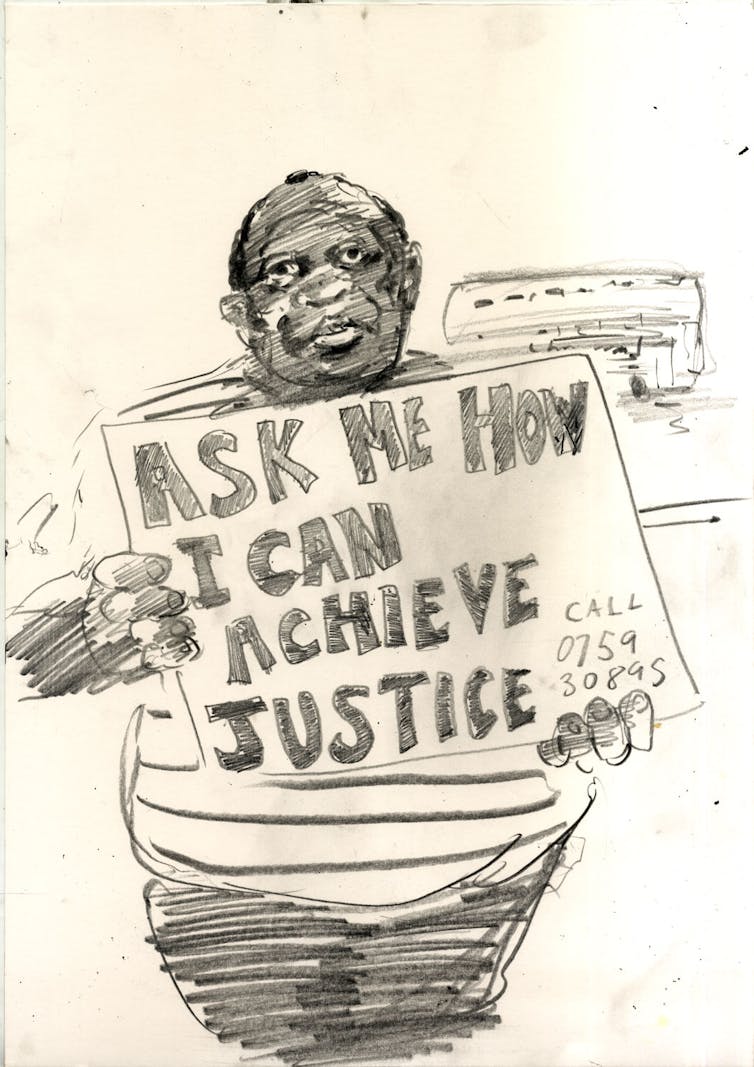

As a travel writer and illustrator, our recent project has involved us documenting and sketching our experiences of visiting seaside towns across England. On our visits, we’ve encountered people living without mains gas or electricity in southern Essex, post-lockdown beach parties turned violent in Bournemouth and COVID-19 conspiracy theories in Torbay and Tynemouth.

We’ve also witnessed the slow death of the high street from the north east down to Weston-super-Mare – along with the growing environmental threat of plastic pollution to the entire English coast. On a brighter note, we’ve appreciated the quirky appeal of these places with their arcade games, fish and chips, full English breakfasts, sticks of rock and endless cups of tea.

Our project has revealed that the bricks and mortar of England’s seaside towns – the retro, elaborate piers and arcades – are just one part of the picture. Party animals on the promenades, families taking selfies in the calm water and many other human stories are what the drawings aim to capture.

There’s a long history of writers and artists collaborating on travel narratives. It was common in the heyday of post-war print with illustrators such as Ben Shahn, Ronald Searle, Paul Hogarth, Linda Kitson and Robert Weaver weaving visual essays into text.

The most famous duo was US journalist Hunter S. Thompson and the British illustrator, Ralph Steadman, who matched one another’s mania in words and images. They produced searing portraits of people and places, magnifying their observations of the real world into caricatures with heightened emotion.

Some of the places we visited are poverty-stricken and marginalised. Clacton-on-Sea in Essex and Torbay in Devon, for example, were recently named in a government report as having some of the “poorest health outcomes” in England. So we wanted to ensure we were reporting on these places fairly, accurately and empathetically and not just fetishising communities as subjects of “poverty porn” – as so often can be the dominant media take.

This is a common risk in travel writing, as highlighted by the US academic Mary-Louise Pratt. Indeed, there is a long and shameful tradition of relatively privileged writers and artists patronising, belittling and misunderstanding those less fortunate than themselves.

This is why it felt important for us to understand the proper social and political contexts of the areas we were visiting. In the case of Jaywick, for example, we learned that the town’s woes were related to years of public underfunding and flaws in the universal credit system. While the closure of the Butlin’s holiday camp nearby in 1983 condemned subsequent generations to irrevocable joblessness.

The use of illustrations also played into this ethical question about representation. Arguably, drawing occupies less fraught terrain than photography – which, as the US writer, filmmaker, philosopher and teacher, Susan Sontag, notes is “context determined”. In other words, photography as a medium can confirm and sustain power dynamics as the subject will often lack access to and control over their own representation.

Unlike a photograph though, a drawing, although capable of capturing a likeness, is inherently subjective and is a creative, impressionistic view of reality. Photography captures people in places, while drawings are about people in places.

As the Australian anthropologist Michael Taussig describes in his book, I Swear I Saw This, a drawing is an articulation of the experience of seeing and witnessing. The drawings reflect the people they depict in more than likeness. They are built line by line, mark by mark and they reflect the struggle and make-up of their subjects bit by bit.

Together we have seen how the English seaside town is many different things: a nostalgia-induced dance with the past, a leisure zone where people forget their daily drudgery, and a fortress in the firing line of ecological and social danger.

Equally varied were the people we met. These include the Essex artists, historians and community members making art to draw attention to flooding, and their counterparts on an anti-plastic pollution project in Southsea.

And then of course there were the publicans, shopkeepers and cafe and snack bar owners who told us about their struggles in the current economic climate. Here’s hoping then that their lockdown woes will be remedied by the new boom in British people spending more time at their own seaside rather than the beaches abroad.![]()

Tom Sykes, Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Portsmouth and Louis Netter, Senior Lecturer in Illustration, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

23.11.21

21.11.21

3.11.21

Five plays about enslavement by Black British women playwrights

“There’s a sidestep that Europe does where it takes itself out of the triangle … I’m never quite sure how that sleight of hand is achieved, but it’s like, slavery, it’s that American thing, we don’t have to worry about it,” said playwright Selina Thompson when talking about Britain’s role in the transatlantic trade of humans from Africa. She’s not wrong. The narrative of slavery in the UK has long been shaped by the celebration of white abolitionists, while the violent part is often obscured.

Most plays, television shows and films about slavery are set in the US. They tend to repeat the same traumatic images of violence against Black people as if there is no other way of getting the horror across than in such visceral and gruesome scenes, particularly those involving Black women.

Speaking about Black British director Steve McQueen’s film 12 Years a Slave, and many films like it, Black feminist cultural critic bell hooks said:

If I don’t see another Black woman naked, raped and beaten as long as I live, I will be just fine.

hooks challenges storytellers to think about how enslavement is represented and to think about how these histories can be explored without re-traumatising Black performers and spectators.

Five recent plays by Black British women have taken this on as they tackle Britain’s missing history, rewriting the record of it as “the country that ended slavery”. They do not resort to violence to show the seriousness of their stories but do so through thoughtful writing and by drawing connections between real stories from our past and our present.

debbie tucker green’s ear for eye

A play in three parts, tucker green’s ear for eye, which has recently been adapted into a film for the BBC, is about the different ways that racism plays out in the UK and USA. While part two explores the power of language and how it can be weaponised to create dangerous stereotypes in the media and in conversation, parts one and three show clear threads that connect contemporary police brutality against Black people to legacies of colonial violence.

Part one portrays African American and Black British parents having “the talk” with their sons about how to conduct themselves when they’re stopped by the police. Many Black parents will know this talk; it stresses how the onus is placed upon young Black men to behave in ways that avoid appearing “threatening”, “aggressive”, “belligerent”, or “provocative”. Yet, the play suggests that any gesture he adopts can be misinterpreted.

Intergenerational conversations about civil rights and contemporary activism are interspersed with scenes describing police officers teargassing Black protesters and using aggressive and humiliating arrest techniques. These are similar to scenes that played out across the world in 2020 as many protested against racial injustice and police violence.

Part three features excerpts from the US Jim Crow segregation laws and the British (Jamaican) and French slave codes, which are read aloud on camera by white actors and non-white actors. While US laws focused on keeping Black people and white people separate, British slave codes legislated the brutal punishments of runaways. Hamstrings were cut following a second attempt to escape and death was the punishment for a third. These infringements of Black human rights show how contemporary violence against Black people stems from much longer histories of racism.

Janice Okoh’s The Gift

The Gift also uses a three-part narrative structure that moves from Brighton in 1862 to the present day rural English countryside.

A story about the adopted African goddaughter of Queen Victoria, Sarah (Forbes) Bonetta are paralleled with present-day Sarah – “a black middle-class woman staying in a Cheshire village with her husband and [white adopted] small child”.

Okoh implies that colonial ideas about race continue to shape understandings in the present. This is clear when well-meaning white neighbours drop by for a cup of tea and microaggressions start to slip out in comments about it being unusual for Black parents to adopt a white child.

Juliet Gilkes Romero’s The Whip

Contemporary resonances are also evident in Juliet Gilkes Romero’s The Whip, which focuses on the abolition of slavery in 1833. This play moves the narrative away from the celebration of white abolitionists by providing a backroom view of British politicians wrangling about abolition in parliament.

Gilkes Romero focuses on the much-obscured part of this legacy – the £20 million borrowed to pay to “compensate” owners of enslaved people for the “loss of property.” This was such a large debt (the modern equivalent of £17 billion) that it was only fully paid off in 2015 using taxpayer’s money. While enslavers were paid off, reparations to those descended from enslaved people have been denied – many of whom have unwittingly paid towards this “compensation” through taxes.

Selina Thompson’s salt.

A one-woman show, salt., part of which has also been adapted for the BBC, narrates a journey that Thompson took on a cargo ship in 2016 to retrace the transatlantic triangular route from Europe to Africa and the Caribbean. Thompson explores African-American scholar Saidiya Hartman’s notion of the “afterlife of slavery”, which is the idea that a racial logic that was established during slavery continues to disadvantage Black people through “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration and impoverishment”.

Thompson shows how colonial dynamics are reproduced in racist and sexist assertions of power on the ship and on the surveillance of her Black female body as she passes through border security controls. She experiences contradictory feelings as a Black woman visiting the dungeons of the notorious Elmina’s Castle in Ghana, where enslaved people were held before being transported, and in Jamaica, where she recognises the implicit racial dynamics of the tourist industry.

Winsome Pinnock’s Rockets and Blue Lights

Rockets and Blue Lights uses a dual narrative framework that is set in the present and the past. One strand portrays the making of a film about JMW. Turner’s 1840 painting, The Slave Ship in the present day. The other strand is set in 1840 as “Londoners Lucy and Thomas try to come to terms with the meaning of freedom” and Turner boards a ship to research the sea for his paintings.

Turner’s painting is believed to be a response to the Zong massacre of 1781, when the captain of a ship ordered the crew to throw 133 enslaved people overboard so that he could make an insurance claim for the loss of cargo.

Pinnock’s use of past and present questions the responsibility of storytellers when exploring enslavement. The Black actress in the fictional film challenges the director’s decision to cut aspects of her story to give more space to Turner’s. This draws attention to how certain stories are written out of historical narratives while others are foreground.![]()

Lynette Goddard, Professor of Black Theatre and Performance, Royal Holloway University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

22.10.21

21.10.21

French Dispatch: four artists whose work was shaped by mental illness

Wes Anderson’s new film The French Dispatch is about the final issue of a magazine that specialises in long-form articles about the goings-on in the fictional town of Ennui-sur-Blasé. The film is an anthology of shorts representing three of the articles.

A piece by the magazine’s art critic (Tilda Swinton) explores the life and late success of the abstract artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro). Talented from a young age, Rosenthaler pursued art with a dogged determination that drove him to slowly lose his mind. In a fit of rage he commits a triple homicide that lands him in jail, where, after a long time away from art, he creates his best work aided by his prison guard and muse Simone (Léa Seydoux).

Artists, like Rosenthaler, burdened with too great a lust for life, or a tragic taste for alcohol, or even intense and murderous desires, are familiar figures in film and fiction. In some films art itself is demonic.

Like everything else, mental illness is understood within the context of its time. In their study of melancholy and genius Born Under Saturn, the art historians Margot and Rudolf Wittkower show how Renaissance artists embraced mental alienation. This was shown by a withdrawn, slothful gloom. Such heavy sadness was considered both the symptom and the price of divine inspiration. It was a means to distinguish their inspiration from the mere “know-how” of craft. A brush with madness was good PR.

So well established did this association become, that if you look up “artist” in the index of writer Robert Burton’s 1620 compendium The Anatomy of Melancholy, you will find one entry. It reads: “ARTISTS: madmen”.

Today, the association of creativity and mental illness often implies regression from an adult and orderly state of mind to one that is primal, impulsive, or infantile. The artist in Anderson’s film is such an example: he is noisy, impetuous, and extravagantly mad. And it is while he is at his “maddest” that he paints his best work.

Here I explore the work of four painters whose work has been shaped by various mental illnesses, highlighting how the idea of the “mad artist” need not be tied up with a loss of control but rather a bid to gain it. It is not always loud. It can be quiet, highly detailed or restrained – as the work of these artists shows.

Richard Dadd

One parallel to Rosenthaler is the Victorian painter Richard Dadd. The career of this brilliant young artist was destroyed by a mental breakdown that today would probably be diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia.

Dadd killed his father, imagining him to be the devil incarnate. He was incarcerated in the criminal lunatic department of Bethlem Hospital. It was as a patient that he painted many of his obsessively detailed masterpieces, such as The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke, (1855-64). The painting contains hidden details that not everyone can see. For instance, in the middle of the painting, I see a figure with a pallid face, wearing a purple cloak, and standing at right angles to the rest of the painting.

It is the work of this period that Dadd is remembered for.

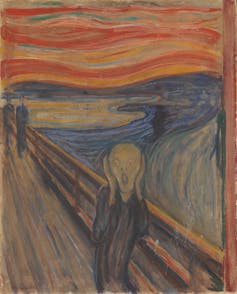

Edvard Munch

A less painful example can be found in the Norwegian painter, Edvard Munch.

Munch’s famous work The Scream (1893) depicts a vision the artist had of “blood and tongues of fire” rising over a fjord. In the foreground, a cadaverous figure clasps his cheeks in agonised shock. A handwritten message on the top left-hand corner of this painting was recently shown to be in the artist’s hand. It reads: “Can only have been painted by a madman.”

Munch saw it as a sign of health that he could express sickness and anxiety in art, and he embraced the idea that madness was a gift that granted him insights denied to others.

Mary Barnes

A striking example of “creative regression” can be found in the artist and poet Mary Barnes. Diagnosed with schizophrenia and refusing to take basic care of herself, Barnes was the first resident of Kingsley Hall, an experimental therapeutic community founded by the psychiatrist RD Laing. She started making images when she was there, initially using her excrement. As one of her psychotherapists described:

Mary smeared shit with the skill of a Zen calligrapher. She liberated more energies in one of her many natural, spontaneous and unself-conscious strokes than most artists express in a lifetime of work. I marvelled at the elegance and eloquence of her imagery, while others saw only her smells.

Barnes went on to have a successful career as an artist.

The phrase “natural, spontaneous and unself-conscious” is a window into the belief that expressive creativity lies in primal regression. As the last example shows, this is certainly not necessarily the case.

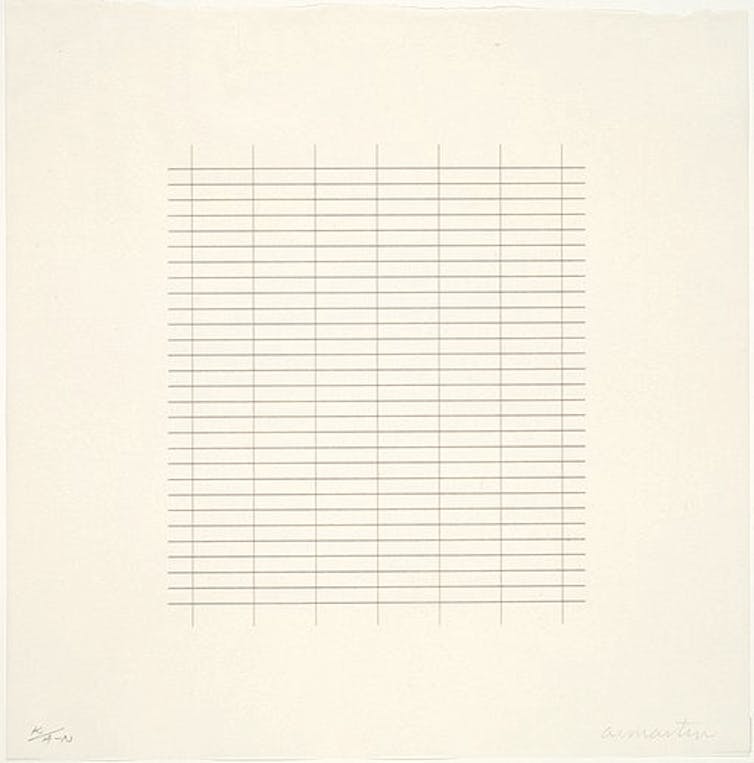

Agnes Martin

The American painter Agnes Martin went through two decades of experimentation to achieve the lucid abstraction that she is known for. In her notes for a talk at the University of Pennsylvania in 1973, she wrote:

The work is so far from perfection because we ourselves are so far from perfection. The oftener we glimpse perfection or the more conscious we are in our awareness of it the farther away it seems to be.

Martin suffered from auditory hallucinations and was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Her calm and methodical paintings, such as Faraway Love (1999), depict abstract states of existence: innocence, happiness, and the sublime. They are as much meditations as visual experiences.

“Sometimes”, she continued, “through hard work the dragon is weakened.”

The example of Martin’s thoughtful and devoted life is in stark contrast to the noisy stereotype of the impulsive and primal genius.

While the paintings of the fictional Rosenthaler and the real Martin are both highly abstract, they sit in stark contrast to each other. Martin’s has a reserved, ordered quality while Rosenthaler’s is bold and unrestrained, splashing across whatever he is using as his canvas. Away from the romantic notions of the great artist expounded in film, as these artists show, most art is about gaining rather than losing control.![]()

Benedict Carpenter van Barthold, Pricipal Lecturer, School of Art & Design, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

14.10.21

Ask the Artist - Bob & Roberta Smith

1.8.21

How could an Italian gallery sue over use of its public domain art?

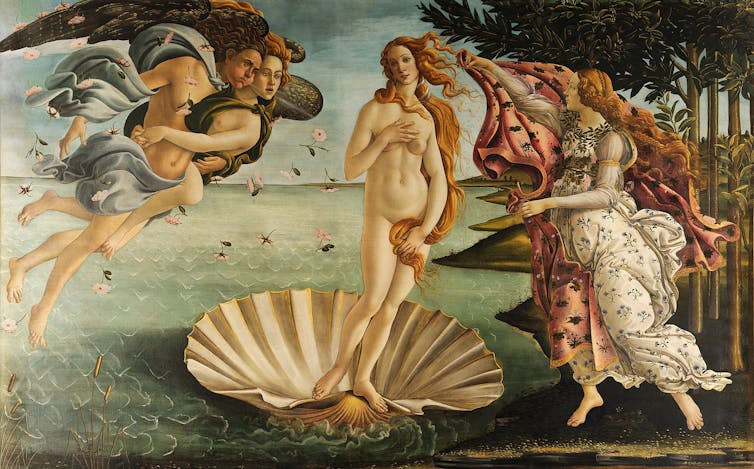

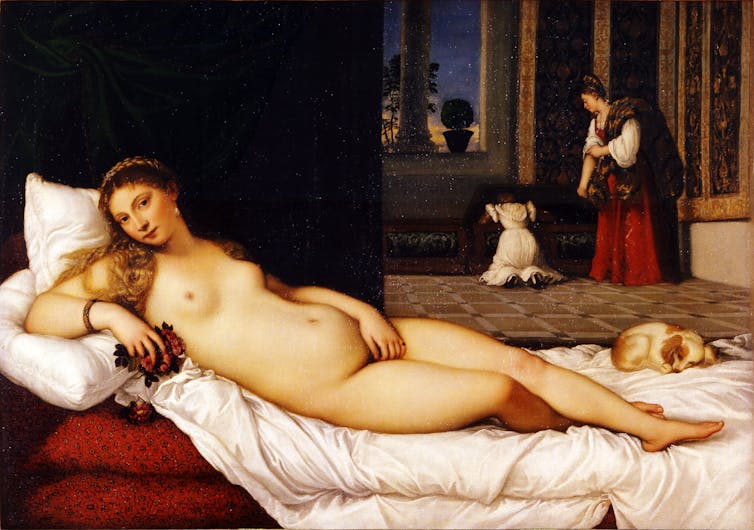

Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus resides within the Uffizi gallery in Florence, Italy. It is believed to have been painted in the mid-1480s and as such is classed as being in the public domain, free from copyright around the world. However, in early July the Uffizi set its lawyers on the website Pornhub, sending the company a strongly worded letter threatening legal action over the unwelcome use of The Birth of Venus along with several of Uffizi’s other masterpieces.

This came in response to the pornography platform’s launch of an online guide to the nude or erotic aspects of artworks in well-known galleries and museums around the world, such as the National Gallery in London, the Museo del Prado in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris and the Uffizi Gallery. Particularly controversial has been Pornhub’s turning of classic artworks into pornographic videos.

It seems the letter has produced its desired effect as Pornhub has subsequently removed any references and artworks pertaining to the Uffizi. But how was it able to create this legal pressure over something in the public domain?

Protection of cultural heritage

The Uffizi has likely invoked rules within the Italian Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code. This law empowers possessors of cultural heritage artefacts to prohibit their commercial exploitation, even where the latter have been created centuries ago.

Italian law strongly protects its heritage. The definition of cultural heritage itself under Italian law is broad: any works which “are of artistic, historical, archaeological and ethno-anthropological interest”. So, if you want to use the image of the Colosseum in your pizza delivery commercial, you may need to pay (at central or local level) a licence fee. An action can be taken to stop any unwelcome or controversial use of the image, for example in a context like porn websites.

In 2017, a court in Florence ordered a ticket agency to stop using the image of Michelangelo’s David on its brochures and website. In the same year, another court in Palermo condemned a bank that had used pictures of the local Teatro Massimo in their advertising campaign. Indeed, in Italy entities which own cultural artefacts can oppose any commercial use of such artefacts. Yet, whether this may happen in other countries remains doubtful.

The issue is not only legal. It also political. In 2014, the Italian culture secretary, Dario Franceschini, strongly protested against US arms engineering company ArmaLite which disseminated ads depicting the David carrying a rifle. Franceschini claimed that the Armed David jeopardised the honour and artistic value of Buonarotti’s work.

Copyright and the public domain

Museum and galleries can also rely on copyright to restrict the use of pictures of public domain pieces within their collection, or anyway charge for such use. Several of them actually do that – for example by declaring that their photographs of old paintings are subject to copyright and cannot be used without paying a fee.

But is that fair? One may note that giving custodians of old artefacts a monopoly over those pictures means to artificially monopolise the underlying works, which should instead belong to the public and be available for anyone to use or reuse it.

There is also an issue of originality. Copyright law only protects original works of authorship. While the originality requirement is interpreted generously in most countries, a threshold does exist. In a US case in the late 90s, Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp, it was held that exact photographic copies of public domain images could not be protected by copyright because the copies weren’t original enough.

Yet, it could be counter-argued that these photographs are not iPhone pics taken by holidaymakers.

Time, labour and skills are needed to move a painting from the gallery or museum to the studio. The photographer must be skilled, good cameras need to be used which avoid glare, and ensure careful light meter readings and faithful colours.

This is an investment – the argument goes - that must be legally protected, for example via a no-photo policy. Indeed, there are economic interests at stake. Take the Uffizi again. It is one of the most visited museums in Italy, and in 2019 around €1 million (£850,000) in revenue came from the sale of photographs of its collection.

While pictures of public domain works are not the focus in the case involving Pornhub, the Uffizi regularly relies on copyright to extract economic profits out of those pictures.

Access to culture

There is also an access to culture angle. Laws which consider pictures of paintings created centuries ago as deserving copyright protection frustrates the most important principle of copyright regimes themselves: namely, that after a specific period of time everyone should be able to use, and build upon, artworks that have fallen into the public domain.

There is the need for a wide category of people to access high quality and faithful representations of public domain works. This is the case of an art university professor showing the pic of an old artwork in class or an art historian publishing the photo in her book. Creators who want to incorporate, build on and reinterpret public domain works should be able to do so on free speech grounds.

Restricting the ability to use these pictures by tampering with copyright law is risky. Yet, it is one thing to rely on criminal law to stop crimes and another to turn copyright upside down so as to indirectly be able to monopolise artistic works, which are simply too old to be protected.![]()

Enrico Bonadio, Reader in Intellectual Property Law, City, University of London and Magali Contardi, PhD Candidate, Intellectual Property Law, Universidad de Alicante

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

23.6.21

13.6.21

Four tips to make the most of your next gallery visit

Going to a gallery can be an escape from the everyday – an opportunity to fall into a moment of reverie in front of an artwork that you know cannot be replicated in print or online. Then there are the spaces themselves: old stately homes, converted power stations and even in carparks. There is nothing quite like a visit to a gallery and now, with COVID restrictions lifting, we can once again go to them. But where to begin and how to make the most of that first trip back?

I have spent the last 20 years working in museums and galleries. In that time, I’ve observed how different people come to these spaces looking for different things.

Whether you’re ready to embrace the world with the full force of a pent-up socialite in need of a culture fix, want to take the children for a day out, or whether you seek solace from solitude, these four tips will help you make the best decisions about when, where and how you bounce back into art and culture.

1. Alone together

Art and cultural spaces are great for a solo visit. At the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA), where I am director, almost 20% of our visitors come alone. Elders, vulnerable adults, refugees and asylum seekers all report feeling safe in the galleries and are often confident to come on their own.

Floating around an exhibition, just taking in the vibe and then reading a novel in the cafe is a perfectly lovely way to spend an afternoon. No one will blink an eyelid that you’re a lone wanderer. Buy the exhibition catalogue and do a deep dive, or skim the surface and zone in and out of art, ideas and people watching.

If you’re seeking quiet time, try arriving early in the morning or a little later in the afternoon to miss the hustle and bustle of midday. We’ve all spent a fair amount of time with ourselves over the past year but this doesn’t mean we have to do everything in one big social dash.

Museum and gallery visits are being prescribed by some GPs as part of an approach to build mental wellbeing and resilience. Art galleries and cultural spaces are great ways to see things anew, to invest in your imagination and build up to other social encounters.

2. A good place for a ‘thunk’

If you’re bringing a clan of any kind, it’s worth remembering that boredom thresholds vary. Keeping different age groups happy can make for a much more enjoyable experience and building activities into your visit can help.

At MIMA, the team have been using artworks to pose “thunks”. A “thunk” is a question that doesn’t have a right or wrong answer. “Where does the sky start?”, “Is soup a food or a drink?”, “What colour is a Tuesday?”.

Also, don’t be afraid to get in contact with the gallery or museum in advance as they may have special resources that you can access.

3. Augment your visit

One of my favourite experiences in a gallery was following a lovely elderly chap give a guided tour to his family. They were captivated. Retired, he would make an advance trip to a museum, read up online and then delight his family with a fascinating tour.

The digital world is filled with all sorts of wonders that can enhance your experience in a similar way. From unique documentary footage, contextual narrative and interviews with artists and curators, this material can bring your visit to life.

Apps such as Smartify, for example, provide behind-the-scenes information about artworks in public collections throughout the UK. This can be a fun way to augment your IRL experience on the day or to bone up in advance.

4. Just one new thing

It can be difficult for museums and galleries to provide sanctuary, the quiet needed for contemplation while also being a fun and engaging family activity at the same time.

Whether you’re looking for the former or latter, with the restrictions we’ve all experienced it can be tempting to overload a visit with expectation and risk feelings of disappointment if, in the event, the reality is somewhat different.

A good approach is to aim to leave the gallery or museum with just one new thing. This could be seeing an entirely new artwork in the permanent collection, having learned one new fact about an artist or a period in time, or simply that brightly coloured pencil you bought in the gift shop.

This will be the first of many visits so enjoy it for what it is and leave feedback – great places really want to know what you enjoyed and what you’d like to see more (or less) of. And if you loved something, tell the world!![]()

Laura Sillars, Dean of the MIMA School of Art and Design, Teesside University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

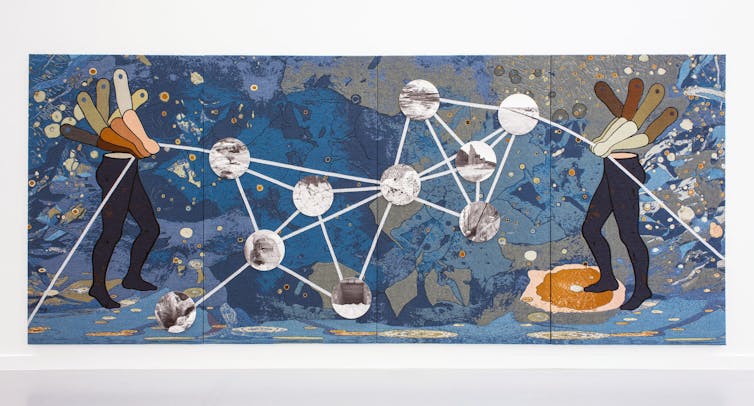

How do artists imagine the world in 2050?| Tate

A Year in Art: 2050 is a two-room exhibition at Tate Modern exploring how visions of the future have taken shape in art across time. It brin...