The author in Nairobi as part of a research project in 2019 into art and community health.

Photo by Georges Mboya, Author provided

Louis Netter, University of Portsmouth

People are dying, critical resources are stretched, the very essence of our freedom is shrinking – and yet we are moved inward, to the vast inner space of our thoughts and imagination, a place we have perhaps neglected. Of all the necessities we now feel so keenly aware of, the arts and their contribution to our wellbeing is evident and, in some ways, central to coronavirus confinement for those of us locked in at home. For some, there are more pressing needs. But momentary joys, even in dire circumstances, often come through the arts and collective expression.

As a lecturer in illustration, I am constantly encouraging students to find an artistic voice and identify, in this crowded world of images, some touchstones to develop their own aesthetic. Art critic and theorist John Berger identified, in the act of drawing, something that is inherently autobiographical – a continual process of refining vision which moves us towards new understandings about ourselves and the world around us.

In this time of crisis and isolation, the role of art becomes more central to our lives, whether we realise it or not. We can easily take for granted the grand buffet of media that is available to us – and I can be guilty of a lack patience when students find it difficult discerning quality amid a sea of memes and amateur artistic indulgence which, to the unsuspecting, can appear to be worthy. The lack of curation on the internet frustrates people like me who value culture and its contribution and equally, are quickly becoming grumpy old men and women.

Whether we like it or not our consumption habits – including media – form who we are, our values, our inclinations. They are a patchwork of beliefs that are also tested in these difficult times.

Art can set you free

I was a high school teacher in Sleepy Hollow, New York, 20 miles away from ground zero when the 9/11 attacks happened. It was a time like now that tested our collective ability to make sense of a new normal and to mourn for the time before that would never come back. A schism in the collective consciousness that everyone struggled to frame, even artists.

Art Speigelman’s graphic novel In The Shadow of No Towers was less of a coherent narrative about 9/11 than an attempt to reassemble his own psyche through the comfort of his own creations and the medium of the comic itself.

A graphic artist’s way of making sense of 9/11.

Amazon

People on social media are sharing favourite Netflix playlists, songs, videos and even artwork to reach out beyond isolation and share what they love. It is naive to think that such lists are mere casual swaps of entertainment enjoyed and recommended. They are an externalisation of the personality of the list maker: the romance enthusiast, the lover of comedies, the thrill seeker, the horror fan, and the aficionado of obscure documentaries.

Read more:

Coronavirus: five musicals chosen by a musicologist to keep you going during lockdown

In this time of restriction, TV, film, books and video games offer us a chance to be mobile. To move around freely in a fictional world in a way that is now impossible in reality. Art connects us to the foreign, the exotic and the impossible – but in our current context, it also connects us to a world where anything is possible. A world out of our grasp for now.

The world we wake up in is a counterfeit reality. Things look the same. Unlike those now familiar films, the descent of humanity is not apparent in the slow shuffle of moaning, glassy-eyed zombies. The threat we face feels like those clever horror movies like The Blair Witch Project, Paranormal Activity and more recent films like The Quiet Place where we rarely see the source of horror. The current moment is best understood as a kind of low hum of anxiety, like the buzzing of a pylon in a field.

The world that was, the world that is

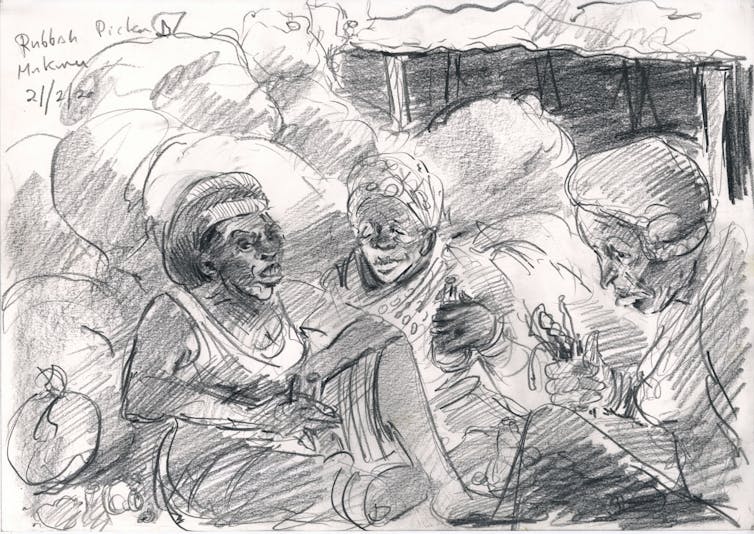

In my travels to Kenya in 2019 and more specifically Nairobi, I drew regularly. I was working on the Tupumue research project, measuring the lung capacity of 2,600 children aged between five and 18 from two areas in Nairobi: the informal settlement Mukuru and the adjacent affluent area Buruburu.

Woman in Mukuru, Nairobi.

Louis Netter

The research team was collaborating with local artists, teachers and community members to develop participatory creative methods to engage with the two communities in the study. The drawings capture my impressions of the vibrant streets of Nairobi and specifically of Mukuru, a large informal settlement, is a visceral flood to the senses.

Women picking through rubbish, Mukuru, Nairobi.

Louis Netter

During an event in which we moved through Mukuru in procession, testing our creative methods for sensitisation which included puppetry, art making (including graffiti), song and dance, a colleague, surveying the crowds of children and people in the narrow, dusty roads, said: “I wouldn’t want to see what a virus would do to this population.”

Man burning electrical wire, Mukuru, Nairobi.

Louis Netter

We are now seeing this unfold and I worry for all of those people living in such close proximity. Self-isolation and the sharing of Netflix lists is an absurd luxury to the people here who live confined in small, steel shacks. Life was hard before COVID-19. After, it could be unbearable.

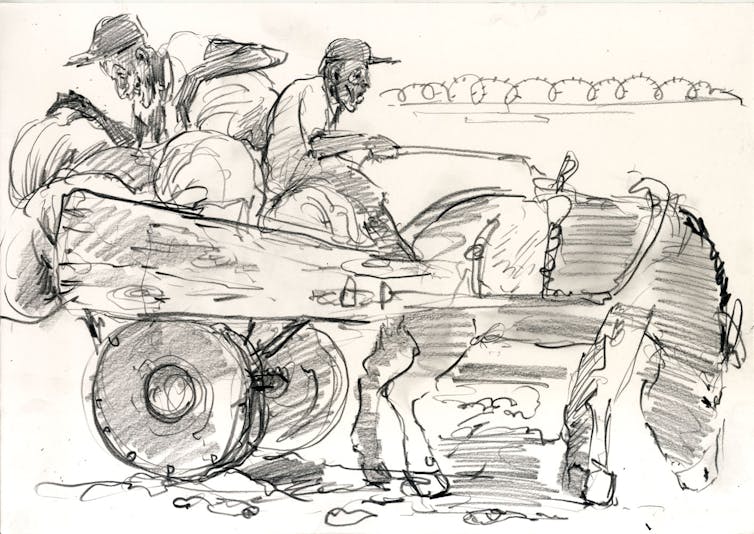

Donkey cart, Buru Buru, Nairobi .

Louis Netter

A life in isolation is nothing new, communities like this have been isolated and invisible to the vast majority of the world for a long time. It is capitalism’s dustbin. When capitalism coughs, these communities perish.

Read more:

Why Africa's journalists aren't doing a good job on COVID-19

So what of the arts in isolation? It might be too early to write that book and paint that picture that captures the buzz of anxiety we all feel. We probably need more time and artists need more sunrises and sunsets to rise and fall on the full, nervous houses. They need more time to listen to the sounds of life interrupted and to mourn for the “world that was”, watching it drift further into the shadows.

Louis Netter, Senior Lecturer in Illustration, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.