Adam Behr, Newcastle University

It seems strangely characteristic of Prince that, despite passing away five years ago, it can feel as if he never left. Apart from the sheer volume of his hits on radio playlists and streaming platforms, his performances are a staple of the flow of social media content that conflates past and present.

There’s some irony in that what is probably his most widely circulated performance – close to 100 million views on one YouTube channel alone – is on someone else’s song, where he steals the show with a barnstorming guitar solo on The Beatles’ While My Guitar Gently Weeps at an all-star tribute to George Harrison. But the moment also perfectly encapsulates why he still seems present all these years after his death, and decades since his dominance of the upper reaches of the charts.

From his sudden appearance halfway through the song, to throwing his guitar in the air and marching off-stage imperiously at its conclusion, it’s a crystallisation of technical mastery, showmanship, supreme confidence (bordering on arrogance) and humour. Pulling grimaces, falling backwards into the security staff, he simultaneously parodies the trope of the “rock guitar hero” while providing a textbook example of it in action – antithesis and apotheosis in one.

Reinventing the music game

This capacity for seemingly winning the game while refusing to play by the rules is what has allowed his persona, as well as his music, to remain salient. For despite his jaw-dropping technique and stagecraft during acts like the Harrison tribute and his 2007 Superbowl Performance, his legacy retains an air of mystery.

This is partly a factor of his musical range, as well as his distinctiveness. From the outset, Prince was an exceptional multi-instrumentalist, capable of recording entire albums himself, and a hard taskmaster. Indeed, aged 20, on his first album he played 27 instruments and clashed with experienced production crew, his creative choices sending the album three times over its budget. His individualism was reflected in a musical output that synthesised the gamut of popular forms – funk, soul, R&B, pop – and at the height of MTV’s power he crashed into mainstream rock on his own terms.

A part of his enigma, though, also resides in his prodigious talent and remarkable work rate. Few artists have matched his ability to produce such a constant stream of releases over the course of his career (Bob Dylan is a possible exception). But what marks Prince out is that the material he made public was the tip of the iceberg. He recorded constantly, taking on all-night recording sessions after gigs, and using mini-studios installed on his tour buses. The 37 studio albums he released in his lifetime are a fraction of his work, the contents of his famed “vault” running to “thousands” of unreleased songs, according to his archivist Michael Howe, including complete albums and finished videos.

Still in control

This is the context for the forthcoming release of Prince’s Welcome 2 America album in July, originally recorded in 2010-11 and the first fully realised studio album to come out after his death. Posthumous releases are, of course, nothing new. From Buddy Holly, through Hendrix to Kurt Cobain, they’re a staple of the recording industry. There’s a wide range of types, and quality, of such releases – from works in progress finished off by collaborators to rough-and-ready demos. What distinguishes the prospect of “new” studio work from Prince is his emphasis on control over his output, and frequent capacity for shelving finished pieces. The work will be his own vision, undiluted by latter-day production decisions or guesswork.

The title track, Welcome 2 America, is redolent of his blend of smooth funk, angular jazz, pop vocals and a spoken word track that looks askance at his surroundings. With echoes of his 1987 state of society address, Sign ‘O’ The Times, it takes swipes at disposable, online culture:

information overload

Welcome 2 America

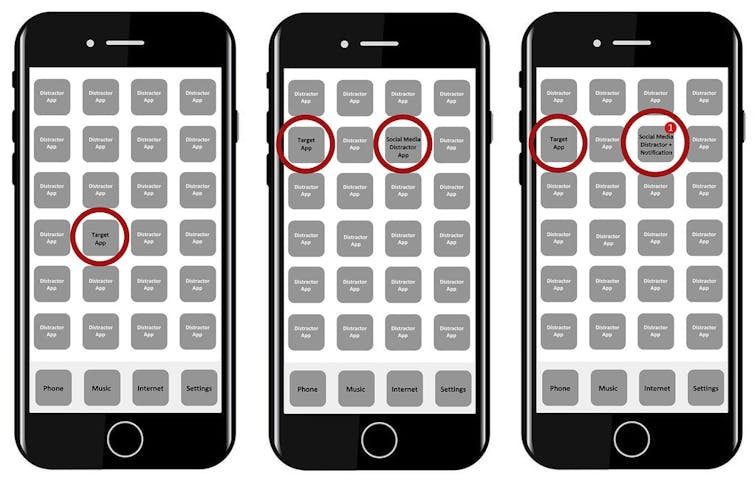

Distracted by the features of the iPhone

Go to school to become a celebrity

truth is a new minority.

Ten years on, his concerns resonate in an era of anxiety over the effects of the web on political culture.

Indeed, for all that his legacy circulates online, Prince himself was chary of the internet and had a variable and fractious relationship with it, alternatively providing exclusive online releases and withdrawing his output from Spotify (until 2017, when his music became available on most streaming services). This was all part of his lengthy battle to retain control over his music. The same struggle that saw him temporarily change his name to an unpronounceable glyph and inscribe “Slave” on his face in protest at his treatment by his label Warner in the early 1990s.

Ultimately, his steadfast refusal to compromise – even if it meant that there were some erratic releases and an awkward relationship with industry during his lifetime – lends the vast body of work in his vault an unusual authority. As well as the sense that he wasn’t finished, it’s also clear that we haven’t heard the last of him yet.![]()

Adam Behr, Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.