28.11.21

26.11.21

R.B. Kitaj's painting of The Wedding

View on YouTube

24.11.21

An artist and a writer visited the English seaside during the pandemic

– this is what they found

Unfurling along the sandy border between town and beach, the English seaside is a place of contradictions – rich and poor, old and new, fun and desperate. Although many of us have a sugary vision of coastal England as tacky entertainment and a bygone refuge from working life, the reality is that many seaside towns are on the front line of contemporary social, economic and political challenges.

Indeed, despite the recent boost to British seaside resorts provided by pandemic-related travel restrictions, since the 1970s there has been a steady decline in the number of people heading to England’s beaches for their holidays – instead favouring cheap deals overseas.

Austerity policies have also hit a lot of coastal towns hard. And many seaside resorts often have a low life expectancy and high concentrations of chronic disease.

In many places, disgruntlement about such problems may have helped to fuel Brexit. Analysis of the EU referendum by Chris Hanretty, professor of politics, at Royal Holloway, University of London, shows that around 100 of the 120 or so constituencies with a coastline voted to leave. While a poll carried out just ahead of the vote by researchers at the University of Aberdeen suggested that 92% of the fishing industry would be voting to leave the EU.

And for all the increases in visitors once restrictions lifted, many seaside towns have really suffered during the pandemic – with many coastal resorts experiencing surging unemployment rates.

The coast must also contend with the grim consequences of the climate breakdown. With rising sea levels comes the increased risk of flooding and in some instances cliff erosion has led to entire buildings falling into the sea.

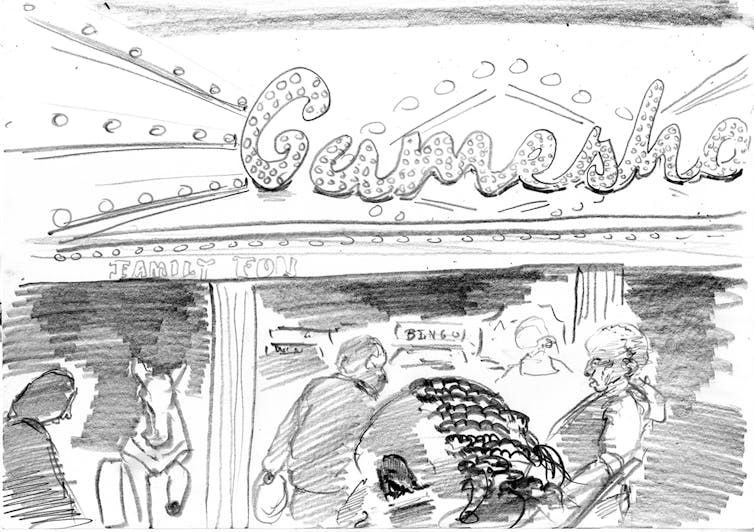

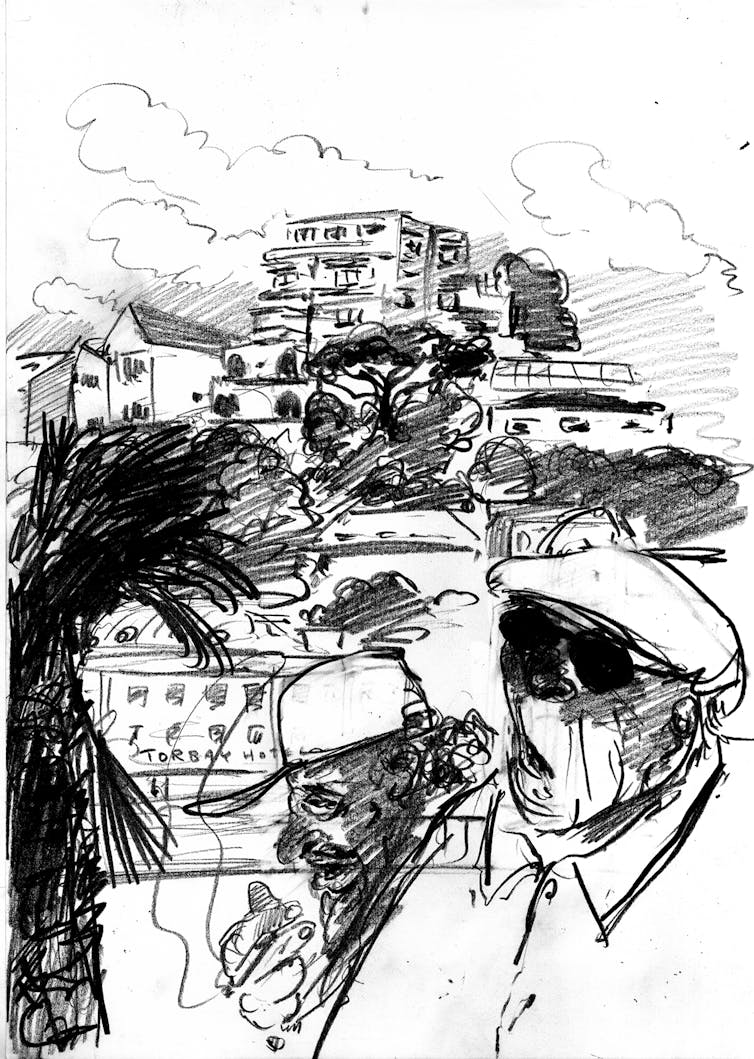

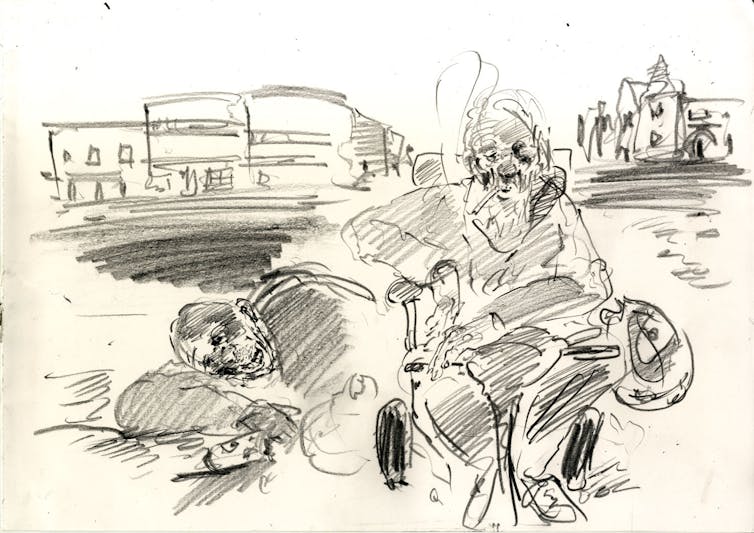

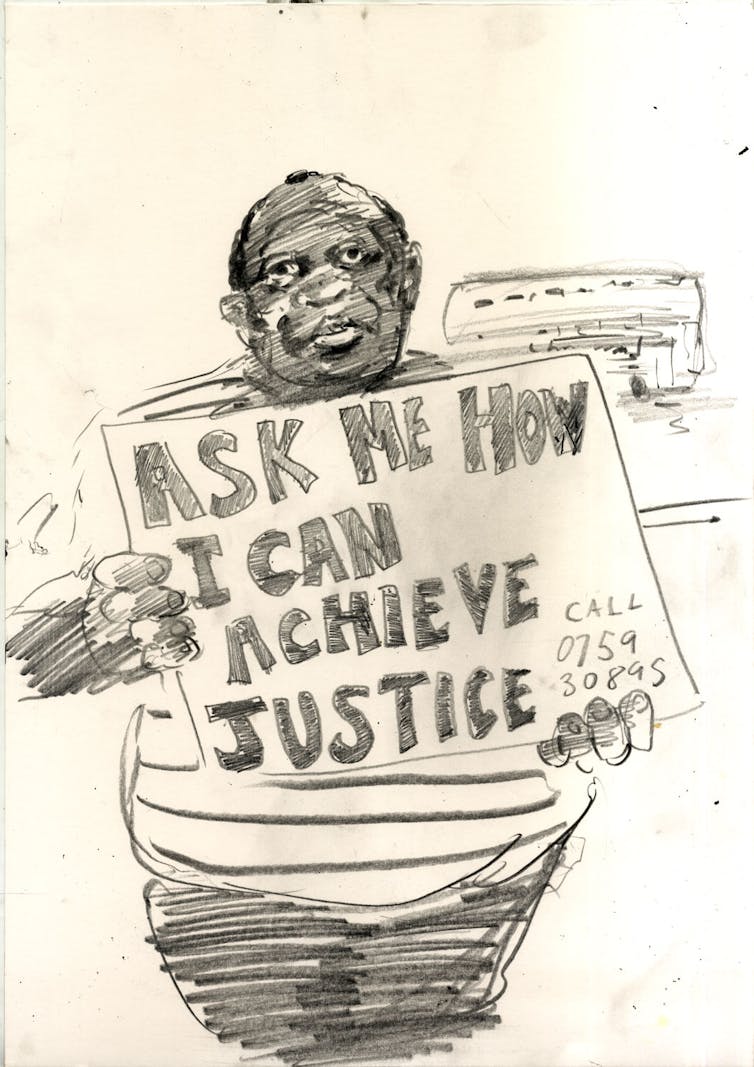

As a travel writer and illustrator, our recent project has involved us documenting and sketching our experiences of visiting seaside towns across England. On our visits, we’ve encountered people living without mains gas or electricity in southern Essex, post-lockdown beach parties turned violent in Bournemouth and COVID-19 conspiracy theories in Torbay and Tynemouth.

We’ve also witnessed the slow death of the high street from the north east down to Weston-super-Mare – along with the growing environmental threat of plastic pollution to the entire English coast. On a brighter note, we’ve appreciated the quirky appeal of these places with their arcade games, fish and chips, full English breakfasts, sticks of rock and endless cups of tea.

Our project has revealed that the bricks and mortar of England’s seaside towns – the retro, elaborate piers and arcades – are just one part of the picture. Party animals on the promenades, families taking selfies in the calm water and many other human stories are what the drawings aim to capture.

There’s a long history of writers and artists collaborating on travel narratives. It was common in the heyday of post-war print with illustrators such as Ben Shahn, Ronald Searle, Paul Hogarth, Linda Kitson and Robert Weaver weaving visual essays into text.

The most famous duo was US journalist Hunter S. Thompson and the British illustrator, Ralph Steadman, who matched one another’s mania in words and images. They produced searing portraits of people and places, magnifying their observations of the real world into caricatures with heightened emotion.

Some of the places we visited are poverty-stricken and marginalised. Clacton-on-Sea in Essex and Torbay in Devon, for example, were recently named in a government report as having some of the “poorest health outcomes” in England. So we wanted to ensure we were reporting on these places fairly, accurately and empathetically and not just fetishising communities as subjects of “poverty porn” – as so often can be the dominant media take.

This is a common risk in travel writing, as highlighted by the US academic Mary-Louise Pratt. Indeed, there is a long and shameful tradition of relatively privileged writers and artists patronising, belittling and misunderstanding those less fortunate than themselves.

This is why it felt important for us to understand the proper social and political contexts of the areas we were visiting. In the case of Jaywick, for example, we learned that the town’s woes were related to years of public underfunding and flaws in the universal credit system. While the closure of the Butlin’s holiday camp nearby in 1983 condemned subsequent generations to irrevocable joblessness.

The use of illustrations also played into this ethical question about representation. Arguably, drawing occupies less fraught terrain than photography – which, as the US writer, filmmaker, philosopher and teacher, Susan Sontag, notes is “context determined”. In other words, photography as a medium can confirm and sustain power dynamics as the subject will often lack access to and control over their own representation.

Unlike a photograph though, a drawing, although capable of capturing a likeness, is inherently subjective and is a creative, impressionistic view of reality. Photography captures people in places, while drawings are about people in places.

As the Australian anthropologist Michael Taussig describes in his book, I Swear I Saw This, a drawing is an articulation of the experience of seeing and witnessing. The drawings reflect the people they depict in more than likeness. They are built line by line, mark by mark and they reflect the struggle and make-up of their subjects bit by bit.

Together we have seen how the English seaside town is many different things: a nostalgia-induced dance with the past, a leisure zone where people forget their daily drudgery, and a fortress in the firing line of ecological and social danger.

Equally varied were the people we met. These include the Essex artists, historians and community members making art to draw attention to flooding, and their counterparts on an anti-plastic pollution project in Southsea.

And then of course there were the publicans, shopkeepers and cafe and snack bar owners who told us about their struggles in the current economic climate. Here’s hoping then that their lockdown woes will be remedied by the new boom in British people spending more time at their own seaside rather than the beaches abroad.![]()

Tom Sykes, Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Portsmouth and Louis Netter, Senior Lecturer in Illustration, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

23.11.21

21.11.21

3.11.21

Five plays about enslavement by Black British women playwrights

“There’s a sidestep that Europe does where it takes itself out of the triangle … I’m never quite sure how that sleight of hand is achieved, but it’s like, slavery, it’s that American thing, we don’t have to worry about it,” said playwright Selina Thompson when talking about Britain’s role in the transatlantic trade of humans from Africa. She’s not wrong. The narrative of slavery in the UK has long been shaped by the celebration of white abolitionists, while the violent part is often obscured.

Most plays, television shows and films about slavery are set in the US. They tend to repeat the same traumatic images of violence against Black people as if there is no other way of getting the horror across than in such visceral and gruesome scenes, particularly those involving Black women.

Speaking about Black British director Steve McQueen’s film 12 Years a Slave, and many films like it, Black feminist cultural critic bell hooks said:

If I don’t see another Black woman naked, raped and beaten as long as I live, I will be just fine.

hooks challenges storytellers to think about how enslavement is represented and to think about how these histories can be explored without re-traumatising Black performers and spectators.

Five recent plays by Black British women have taken this on as they tackle Britain’s missing history, rewriting the record of it as “the country that ended slavery”. They do not resort to violence to show the seriousness of their stories but do so through thoughtful writing and by drawing connections between real stories from our past and our present.

debbie tucker green’s ear for eye

A play in three parts, tucker green’s ear for eye, which has recently been adapted into a film for the BBC, is about the different ways that racism plays out in the UK and USA. While part two explores the power of language and how it can be weaponised to create dangerous stereotypes in the media and in conversation, parts one and three show clear threads that connect contemporary police brutality against Black people to legacies of colonial violence.

Part one portrays African American and Black British parents having “the talk” with their sons about how to conduct themselves when they’re stopped by the police. Many Black parents will know this talk; it stresses how the onus is placed upon young Black men to behave in ways that avoid appearing “threatening”, “aggressive”, “belligerent”, or “provocative”. Yet, the play suggests that any gesture he adopts can be misinterpreted.

Intergenerational conversations about civil rights and contemporary activism are interspersed with scenes describing police officers teargassing Black protesters and using aggressive and humiliating arrest techniques. These are similar to scenes that played out across the world in 2020 as many protested against racial injustice and police violence.

Part three features excerpts from the US Jim Crow segregation laws and the British (Jamaican) and French slave codes, which are read aloud on camera by white actors and non-white actors. While US laws focused on keeping Black people and white people separate, British slave codes legislated the brutal punishments of runaways. Hamstrings were cut following a second attempt to escape and death was the punishment for a third. These infringements of Black human rights show how contemporary violence against Black people stems from much longer histories of racism.

Janice Okoh’s The Gift

The Gift also uses a three-part narrative structure that moves from Brighton in 1862 to the present day rural English countryside.

A story about the adopted African goddaughter of Queen Victoria, Sarah (Forbes) Bonetta are paralleled with present-day Sarah – “a black middle-class woman staying in a Cheshire village with her husband and [white adopted] small child”.

Okoh implies that colonial ideas about race continue to shape understandings in the present. This is clear when well-meaning white neighbours drop by for a cup of tea and microaggressions start to slip out in comments about it being unusual for Black parents to adopt a white child.

Juliet Gilkes Romero’s The Whip

Contemporary resonances are also evident in Juliet Gilkes Romero’s The Whip, which focuses on the abolition of slavery in 1833. This play moves the narrative away from the celebration of white abolitionists by providing a backroom view of British politicians wrangling about abolition in parliament.

Gilkes Romero focuses on the much-obscured part of this legacy – the £20 million borrowed to pay to “compensate” owners of enslaved people for the “loss of property.” This was such a large debt (the modern equivalent of £17 billion) that it was only fully paid off in 2015 using taxpayer’s money. While enslavers were paid off, reparations to those descended from enslaved people have been denied – many of whom have unwittingly paid towards this “compensation” through taxes.

Selina Thompson’s salt.

A one-woman show, salt., part of which has also been adapted for the BBC, narrates a journey that Thompson took on a cargo ship in 2016 to retrace the transatlantic triangular route from Europe to Africa and the Caribbean. Thompson explores African-American scholar Saidiya Hartman’s notion of the “afterlife of slavery”, which is the idea that a racial logic that was established during slavery continues to disadvantage Black people through “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration and impoverishment”.

Thompson shows how colonial dynamics are reproduced in racist and sexist assertions of power on the ship and on the surveillance of her Black female body as she passes through border security controls. She experiences contradictory feelings as a Black woman visiting the dungeons of the notorious Elmina’s Castle in Ghana, where enslaved people were held before being transported, and in Jamaica, where she recognises the implicit racial dynamics of the tourist industry.

Winsome Pinnock’s Rockets and Blue Lights

Rockets and Blue Lights uses a dual narrative framework that is set in the present and the past. One strand portrays the making of a film about JMW. Turner’s 1840 painting, The Slave Ship in the present day. The other strand is set in 1840 as “Londoners Lucy and Thomas try to come to terms with the meaning of freedom” and Turner boards a ship to research the sea for his paintings.

Turner’s painting is believed to be a response to the Zong massacre of 1781, when the captain of a ship ordered the crew to throw 133 enslaved people overboard so that he could make an insurance claim for the loss of cargo.

Pinnock’s use of past and present questions the responsibility of storytellers when exploring enslavement. The Black actress in the fictional film challenges the director’s decision to cut aspects of her story to give more space to Turner’s. This draws attention to how certain stories are written out of historical narratives while others are foreground.![]()

Lynette Goddard, Professor of Black Theatre and Performance, Royal Holloway University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kids React to Art - Cildo Meireles's Babel | Tate #kidsreact #funnyvideo

📻 We asked kids to react to Cildo Meireles's Babel, one of 25 artworks celebrating Tate Modern's 25th birthday, and this is what th...