Historically, it was a popular destination for elderly and working-class people and it had a particularly strong presence in the north of England, where ...

* The full article is published here...

29.11.19

28.11.19

Jonathan Miller: man with two brains who straddled the worlds of arts and science

Jonathan Miller, still from The Body in Question (1978).

BBC Pictures

Rohan McWilliam, Anglia Ruskin University

Pretty much all the tributes to Jonathan Miller, who has died aged 85, end up using the term “Renaissance Man” at some point. Miller had a mastery of arts and science that few achieve – he was, at various points, a doctor, an actor, a director, a writer, a darling of the TV chat show circuit and a sculptor.

For many, he will be remembered as one of the dazzling four performers in Beyond the Fringe (along with Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett), who launched in 1960 the satire boom which later gave us Monty Python. For others, Miller is known for his major documentary series, The Body in Question (1978), which – literally – opened up the body and – less literally – medical history in much the same way that Kenneth Clarke opened up Civilisation for a mass audience.

But Miller was also known for a remarkable number of pioneering theatre and opera productions, such as the English National Opera’s enduringly popular “mafia-style” Rigoletto, with its 1950s New York setting.

Miller clearly made a huge difference but how can we define his importance, especially as it was spread across so many fields?

Two cultures

Miller’s arts and science background enabled him to cross disciplinary boundaries and make exciting connections. He was the perfect riposte to the Two Cultures debate (1959-62) between F.R. Leavis and C.P. Snow, which focused on the lack of conversation between arts and science. If we consider how scholars now embrace interdisciplinarity, we should note that Miller blazed the trail.

Miller should also be viewed as one of the architects of liberal Britain in the post-war period. He rejoiced in being an irreverent free thinker (presenting a television series about his atheism) while saying, on one occasion in a lecture he gave, that censorship was about as ridiculous as adjusting one’s clothing when leaping out of a burning building. Miller paid no regard to traditional ways of presenting a play. His 1970 production of The Tempest broke new ground by presenting it as a drama about colonialism – now a standard interpretation.

Jonathan Miller, far right, in Beyond the Fringe, 1962, with, from left, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Peter Cook.

Friedman-Abeles, New York

Miller was the product of what Frederick Raphael called the “glittering prizes” generation of the 1950s in which Oxbridge-educated graduates, such as theatre director Peter Hall and TV presenter David Frost, moved effortlessly into major posts in the arts and the media. A star turn in the Cambridge Footlights led Miller to Beyond the Fringe, which became a huge hit.

He performed in the show while carrying on with his medical training by day, but, having become a doctor, he was soon seduced away to become the producer of the BBC arts programme, Monitor, where his focus on figures like Susan Sontag led to accusations of pretentiousness.

Private Eye frequently ridiculed him as a “pseud”. This was not helped by his 1966 film of Alice in Wonderland, which dispensed with Lewis Carroll’s wit and interpreted the story as the adolescent dream of a girl on the verge of puberty.

The popular press wrongly claimed he was deploying Freud to sexualise a children’s story (or creating an “X-certificate Alice”). The ambition of Miller’s version is a rebuke to the more conventional literary adaptations on television today.

Theatrical trailblazer

At the National Theatre Miller directed Laurence Olivier in The Merchant of Venice (1970), adopting a Victorian setting that brought out the links between capitalism and antisemitism in the play. He quickly gained a reputation for presenting classical plays in the costumes of another period so as to emphasise a particular aspect of them. In fact, most of his productions were presented in period, paying careful attention to the visual culture of which they were a part.

He was influenced by the social psychologist Erving Goffman, which is why his productions paid careful attention to manners, hand gestures, silences and the varying protocols of conversation.

When he came to direct Eugene O'Neill’s A Long Day’s Journey into Night with Jack Lemmon (1986), he notoriously made the very long play run much shorter by having the protagonists frequently speak over each other, imitating speech patterns in ordinary life.

There was a strongly anthropological feel to his productions. Miller’s ability to make intellectual connections made him unusual among modern directors. He once complained to me that Peter Hall (with whom he had a long-running feud) never bothered to read a book. Hall, for his part, felt Miller took on the task of directing in the same spirit as if he was writing for the New York Review of Books.

It was, however, in opera that Miller really made his mark, travelling the world putting on productions for many of the great opera houses. Miller brought psychological realism to the operatic stage, insisting that singers also had to act.

Although he directed productions from across the repertoire, he had a love of Mozart as a great musical dramatist. He became a major figure in opening up opera to a wider audience, stripping the form of its exclusivity.

Miller became the producer of part of the BBC Shakespeare series in the early 1980s where he developed effective ways of doing Shakespeare by using the close up for soliloquies and employing contemporary paintings for inspiration. His Taming of the Shrew enjoyed the casting coup of John Cleese as Petruchio. When he took over the Old Vic in 1988, he produced the most intellectually ambitious repertoire that London has seen in a long time. His production of George Chapman’s Bussy D'Ambois (1603) was probably the first since the 17th century.

Two minds

Kate Bassett called her 2012 biography of Miller In Two Minds, which captures the split in his life. Miller was haunted by his decision to abandon the medical profession where he had hoped to excel.

Jonathan Miller’s pop-up book, The Human Body.

Amazon

But his restless intellectual energy was, however, a key part of the arts scene over four decades and he became a major force in making scientific knowledge available (he was happy to produce a pop-up book about the body and a book about Darwin in comic book form).

Miller felt he was never truly appreciated in his own country. Yet this was not true – he was hugely admired in Britain. Few did more to excite people about the arts and the sciences or make them confront the world of ideas in an accessible way. For those who grew up with Miller, paying tribute to him is a debt of honour.

Rohan McWilliam, Professor of Modern British History, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

26.11.19

Hong Kong Museum of Art to reopen in spite of escalating violence of pro-democracy protests

The Hong Kong Museum of Art (HKMoA) will press ahead with its ... tracing the lineage of Hong Kong art and a loan show from Tate in the UK, ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

23.11.19

For the many not the few

For the many not the few

by Paul Garrard

DIGITAL DOWNLOAD + STREAMING on BandCamp

Any money I make from people downloading this track before the end of the year will all be donated to the Labour party. Please pay what you can.

by Paul Garrard

DIGITAL DOWNLOAD + STREAMING on BandCamp

Any money I make from people downloading this track before the end of the year will all be donated to the Labour party. Please pay what you can.

Art collectors turn up with 'pockets full of cash' as secret artist's lifework of 400 paintings goes on ...

ART collectors turned up with “pockets stuffed full of cash” after a retired ... Labourer Eric Tucker's love of art was only discovered in July last year .... Lawrence Stephen Lowry, born in 1887, is renowned for his artwork that captured the life of industrial districts in North West England. ... News · UK News.

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

22.11.19

Nearly 1.5 million young people have registered to vote

Nearly 1.5 million young people have registered to vote for election 2019 – and more could join them

Ben Gingell/Shutterstock

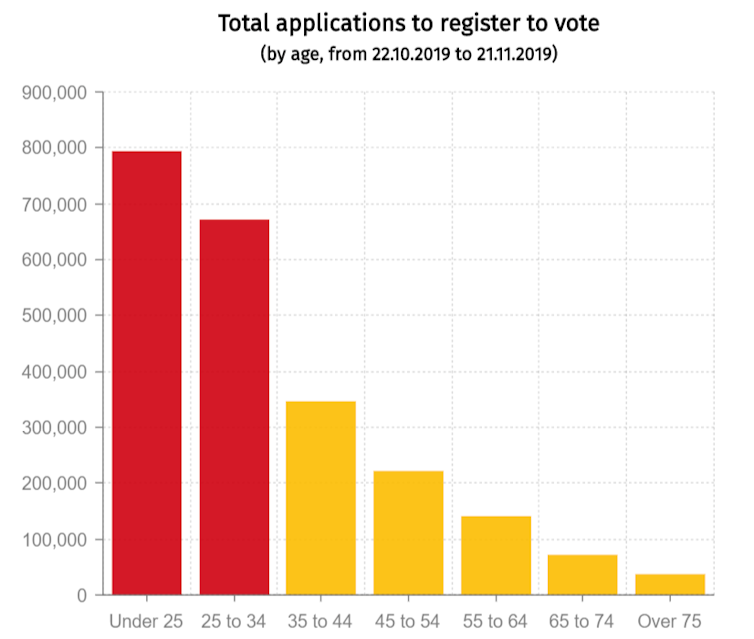

According to the gov.uk live statistics on voter registration, from the October 22 to the November 19, just under 1.5 million people aged under 34 applied to register to vote (1,465,857 to be precise). Under-34s make up the majority – 64% – of applications to vote.

These numbers are remarkable. For comparison, in the same period in the 2017 general election campaign (so from the announcement of a snap election on April 18 to May 16, 1,118,534 under-34s applied for their vote. That’s a rise of 31% on 2017.

However, millions of people – especially young people and minority ethnic groups – are still unregistered. With one week to go before the registration deadline of November 26, the Electoral Commission published research that said one in three eligible teenagers still hadn’t registered to vote.

Add that to 32% of 20 to 24-year-olds and 26% of 25 to 34-year-olds, and you will realise there is still a long way to go. Compare that with 6% of pensioners and 17% of the whole population to see the problem. Young people are motivated by a wide range of issues that may differ from what older voters want – as we’ve seen with Brexit. Their party preferences are also often different from older voters. Make no mistake, though, young people will lose their vote if they don’t register.

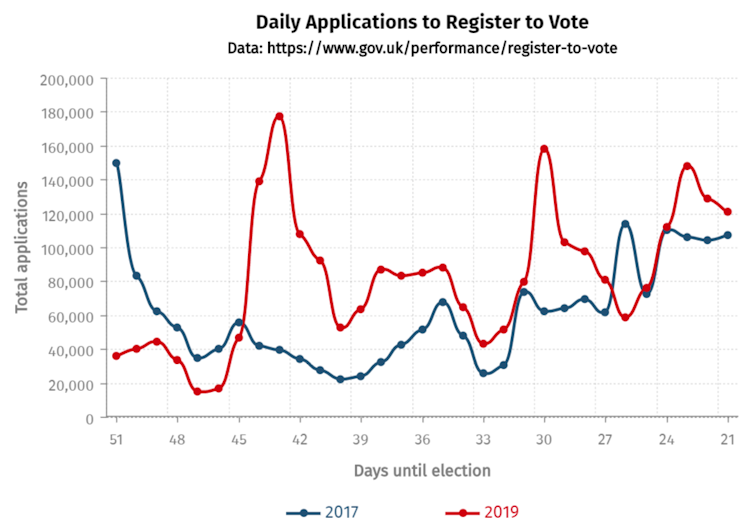

Daily applications to register to vote.

UK Government

The Electoral Commission also points out that one in four people from a black or Asian ethnic background are still unregistered to vote. They will also lose their vote unless they register by the November 26 deadline.

Government reforms to the election rules in 2014 made it more difficult for young people – especially students – to vote. Now, every person has to register themselves before a given deadline – one person can’t do it on behalf of their household. According to research, this had the worst effect on students, young adults and private renters. Campaigns to change the registration rules continue, but, for now, voters are stuck: register to vote, or lose your vote.

It’s also true that lots of people don’t know they have the right to register to vote. For instance, it’s not always known, even among Commonwealth and Irish citizens in the UK that qualifying Commonwealth citizens and Irish citizens in the UK have the right to vote in general elections, and can register to vote just the same way: https://www.gov.uk/register-to-vote

Deadline day surge?

In 2017, the single biggest day for voter registration was deadline day, and it’s probably going to be the case in 2019 too. Deadline day is November 26. Voters can register online at any point before then.

Total applications to register to vote, by age.

UK Government

The big question for young voters may be where they decide to vote. Students can register twice if they have a home and term-time address – although they can only vote once. Lots of websites are offering tools to help students pick where they vote, like this comparison app from the Guardian, which will compare your home constituency to your university constituency. Let’s say your home address is in a very “safe” constituency, where the current MP’s majority is really high. Let’s also say your university address was very close in the 2015 election. In this case, you might fancy voting in your university constituency, because it’s a closer fought thing. If lots of students organised to do this, it could really shake up university cities like Bath, Bristol and Sheffield.

Young people have been taking to the streets this year for climate change, but will they vote, too?

Kevin J.Frost/ Shutterstock

In 2017, postal voters were 16% more likely to vote and lots of students, who may be moving home from university for the Christmas holidays, might choose a postal vote so they can pop their ballot in the post before they move.

Getting a postal vote requires filling in a form) and sending it to your local electoral registration office by the deadline at 5pm on November 26. You can find the address to send it online, or use this tool: https://www.gov.uk/get-on-electoral-register.

There are even campaigns like Votey McVoteface, run by folks who live on canal boats, to help people without a fixed address register to vote. As the charity Crisis points out, you still have the right to vote if you don’t know where you’ll be living on December 12, and there are ways to register and people to support you.

Why are more young people registering to vote?

It’s hard to say at this point why there’s a surge in electoral registration. What we do know is that every day but one of the 2019 campaign, more people have applied to vote than at the corresponding day in 2017. It’s not a flash in the pan.

Some caveats apply. Going on the website and applying to register is not exactly the same as registering, because it’s possible to apply when you’re already registered. It’s so easy to apply that many people may be re-applying, just to be safe, even though they’re already registered. And young people are more likely to need to register, as first-time voters, or as people who have recently moved home and changed address.

However, the rise in registration is still fairly remarkable for an election that many pundits thought would leave voters feeling “poll fatigue”. Quite the opposite: if voter registration is anything to go by, it seems like people out there are fired up for the election.

And, with 64% of applications to vote coming from under-34s, raises the question: will young people vote in December, and for whom? Will students get smart about where they choose to vote? Will we see young people using postal votes to avoid the December cold?

Only one thing is for sure. To vote, young people have to register.

Click here to subscribe to our newsletter if you believe this election should be all about the facts.

Benjamin Bowman, Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

20.11.19

Plymouth students stage protest at Tate Britain in London

Students from Plymouth College of Art descended on Tate Britain in London to hold a protest for the gallery's Late at Tate Britain: Social Justice event.

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

19.11.19

17.11.19

On my radar: Sarah Hall's cultural highlights

The English novelist on an ideal fusion of art and retail, the inspiring verse of Kathleen ... Hall now divides her time between the UK and North Carolina. .... Guardian reporting is based in fact, and as a news organisation, we are ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

3 LGBTQ+ Icons Visit Tate Britain – Sasha Velour, Munroe Bergdorf and Leo Kalyan

Three LGTBQ+ advocates visit Tate Britain to interpret and make sense of artworks on the basis of their own identities and experiences. Discover them reveal LGBTQ+ histories and identities of works in the collection.

16.11.19

Is Boris Going To Sell The NHS To Trump?

The Labour Party say he will, the Tories deny it. But what’s the truth?

15.11.19

From Africa to Peckham: how we decolonise culture by rehumanising people

[Re]Engtanglements, Author provided

It’s an extraordinary collection of portraits from Nigeria and Sierra Leone taken between 1909 and 1915, when Britain was at the height of its empire. The archive shows a vast array of faces – of women, children and men – some distant, some suspicious, some proud, some confused, some joyous. Most are photographed against a canvas backdrop, some with number boards above their heads, all of them silent.

Many of our museums and archives are filled with such traces of Britain’s colonial past, and exist as troubling presences in our public institutions. Many of these collections illustrate the way academic subjects such as anthropology, geography, linguistics and botany are entangled with Britain’s colonial history.

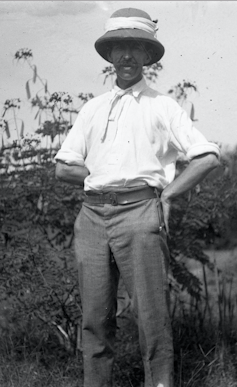

British anthropologist Northcote Thomas.

Royal Anthropological Institute, Author provided

For decades, much of this material has remained hidden, its access largely restricted to academic researchers. There has been a reluctance to confront these relics of outmoded and objectionable ideologies. Now, amid renewed calls to “decolonise” our cultural institutions, there is a desire to open up the colonial archive to new forms of scrutiny.

I have been leading a collaborative project called [Re:]Entanglements, which exemplifies this new spirit of openness through art, film and community engagement.

The project explores this remarkable photographic archive of people’s faces, as well as recordings, artefacts, botanical specimens and fieldnotes – the legacy of a series of anthropological surveys funded by the colonial governments of Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone in the first two decades of the 20th century. These surveys were led by Northcote Thomas (1868-1936), the first government anthropologist to be appointed by Britain’s Colonial Office.

Reframing the past: art, outreach and fieldwork

On the one hand, [Re:]Entanglements seeks to better understand the historical relationship between anthropology and colonialism in the early 20th century. On the other, crucially, it is exploring the significance of these archives for different communities in West Africa and the UK today.

The research team has retraced Thomas’s survey itineraries in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, bringing back copies of photographs and sound recordings to the descendants of those surveyed over a century ago. It has been a privilege to witness people listening to the voices of their ancestors and seeing the faces of their great-grandparents, often for the first time.

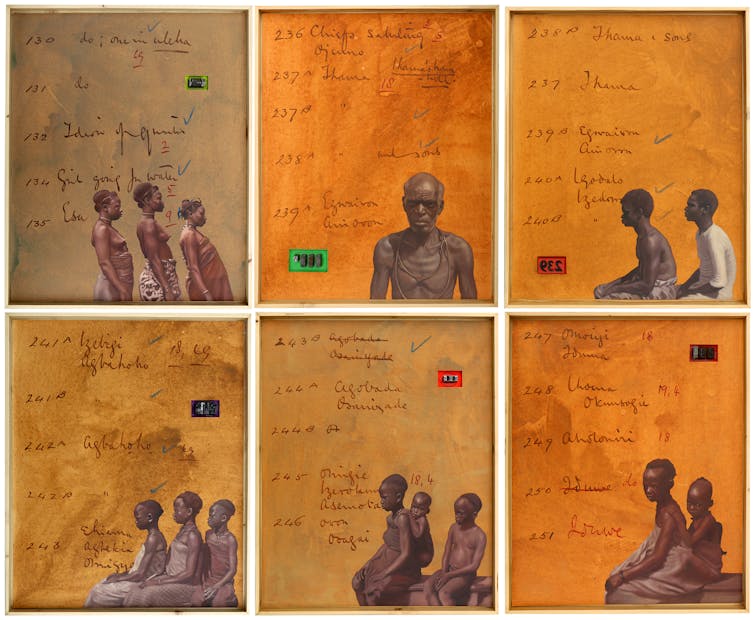

Nigerian artist Kelani Abass’s mixed media work that uses Northcote Thomas’s survey material.

Kelani Abass, Author provided

The project has also established collaborations with contemporary artists in West Africa, inviting them to respond to the archive and illuminate its underlying politics through their work. The Igbo artist, Chukwunonso Uzoagba, for example, has restaged one of Thomas’s photographs of a traditional wrestling festival as a contest between an indigenous wrestler and Thomas himself, representing the struggle between colonised and coloniser.

Another artist, Kelani Abass, has produced a series of 17 mixed-media works called Colonial Indexicality based on the albums of Thomas’s photographs that we discovered in the National Museum in Lagos. These are the only surviving records of Thomas’s surveys in Nigeria.

Abass’s work captures the fading textures of the archive and the bureaucracy involved in documentation, and stands as a visually arresting comment on the fragility of memory. It also lays bare the paradox of colonialism as a force that both destroyed traditional ways of life and preserved them.

The view from London

Other forms of public engagement with this project have been taking place in the UK as well. A young people’s initiative at the South London Gallery, for example, includes an exploration of Peckham’s many connections with Nigeria and Sierra Leone across the generations.

Another initiative resulted in the film I made with Chris Allen of production company The Light Surgeons. Called Faces|Voices, the film has just won the best research film prize for 2019 at the Research in Film Awards (RIFA).

Although researchers have written a great deal about the politics of representation of African people, in Faces|Voices we wanted to explore a wider range of responses to Northcote Thomas’s photographs – particularly among British people with an African heritage.

A British woman looks at an image of a Nigerian woman from a 1911 colonial survey in the film Faces|Voices.

[Re]Entanglements, Author provided

We invited a number of people from across London – some with direct links to the places in which Thomas worked, and some engaged in community education, activism or the reparations debate – to confront some of the more problematic images produced by the English anthropologist. These colonial-era portraits sought to document the physical characteristics of people belonging to different ethnic groups.

For many, these epitomise the violence of colonial science, treating individuals as specimens to be collected, sorted and categorised into racial or tribal types. They make up about half of around 7,500 photographs that Northcote Thomas took in West Africa.

Woman and child photographed in Southern Nigeria in 1911.

NW Thomas, Author provided

Since the many West African faces photographed for Thomas’s archive have no voice, we can only guess what the experience of being photographed by this pith-helmeted anthropologist may have been like. Was it violent or humiliating? Was it an amusing distraction from everyday chores? Was it empowering? What can we read in the mute expressions of those photographed?

In Faces|Voices, we find that the same photograph seen through different eyes can elicit quite different responses. Where one person sees coercion, another detects merely boredom. The crushing experience of colonial oppression is discerned in one subject’s expression. Optimism and resilience is read in another’s.

It is clear, then, that the “meaning” of these photographs has as much to do with what the viewer brings to the image as what the image presents. Perhaps most surprising is the sympathetic view of the face of Northcote Thomas himself. While for one viewer the image of Thomas exemplifies the “stiff upper lip” of a British colonial, others remark on what they see as kindness, integrity and humanity.

Young woman photographed by Northcote Thomas in Southern Nigeria in 1911.

NW Thomas, Author provided

As the legacy of a colonial project, the capacity of these photographs to unsettle us is beyond question. But our film Faces|Voices also complicates any simple reading of these images beyond the idea of “colonised” and “coloniser”. There is laughter too in the colonial archive, and the voices of the black British people in the film articulate a need for us to re-humanise the subjects of Thomas’s photographic portraits.

While it is crucial that we confront the difficult histories embodied in such archives, it is important that we do so attentively, mindful of their complexities and contradictions.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

14.11.19

Street art brightens up village bus shelters

Colourful street art designs have been created by youths in a bid to brighten up bus shelters across a West Cumbrian village. Youngsters who attend ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

12.11.19

Berlin Wall: how techno music united Germany on the dance floor

When the Wall came down: Berlin 1989.

Raphaël Thiémard, CC BY-SA

In the wake of the demolition of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, something strange and wonderful happened. Youth from both East and West Germany converged on the space cleared by the wall’s demolition to party – and their preferred soundtrack was techno music.

Much has been written about the role of techno in Berlin and music’s power to create or enhance social cohesion. Three conditions had to be met in 1989 Berlin for music to take on this role: young people were needed who were eager to dance and unafraid of new experiences, social entrepreneurs to organise these raves and available space to set up the decks and dance floors.

In the mid 1980s, with perestroika and glasnost reverberating in East Germany, churches started playing an increasingly important role in East Berlin. Although churches had continued to operate in the GDR, it took conviction and courage for people to show their opposition to a communist regime. Churches continued to provide safe spaces for people to peacefully congregate. But they were also explored as alternative venues for concerts.

Bluesmessen (church services with music for young people) became increasingly popular, as these events were not governed by the GDR law (Veranstaltungsgesetz) and escaped state censorship. After years of artistic censorship through the Lektoratskommission (a state assessment panel for lyrics and music) and the need for the permits to play pop music live (Spielerlaubnis), what young people in East Germany wanted was to be authentic and immediate.

The West German punk band Die Toten Hosen, for example, played two illegal gigs in 1983 and again in 1988 at churches in East Berlin. The need to produce and consume nonconformist music was evident long before the wall came down.

West German punk band, die Toten Hosen, playing the Hoffnungskirche in East Berlin, 1988.

Mark Reeder, Author provided

But what was perhaps needed was a new kind of music – something not as culturally or politically loaded as punk, for example, which meant different things in the two parts of the city (not least because punks did not officially exist in the GDR). And then techno happened.

Unification through dance

In 1989, two different youth cultures met on the dance floor. West Berlin was known as a place in which young men from West Germany could avoid military service because of its demilitarisation after World War II. This lack of compulsory military service tended to attract a particular kind of young person, one that helped define a very alternative, creative and artistic scene in West Berlin.

Out of this scene came entrepreneurs who were used to organising parties and continued to do so in parts of the city that had become available when the Wall was demolished. Abandoned buildings on the former death strip that had previously divided the city were soon appropriated as dance spaces. The newly elected Berlin Senate condoned this, even though many of these spaces were being used illegally.

It is in here that the social entrepreneurs of West Berlin met young people from East Berlin who wanted to express themselves authentically and without state surveillance. The act of dancing helped to connect people in a way that politics in Germany still to this day struggles to achieve. Many East Germans continue to feel inferior and see German unification as an annexation of their former state, losing their currency (and for many, their savings), their educational system, employment protection and even their street names. Nobody ever told them what a free market economy means and how you compete successfully for jobs, pay raises or promotions.

Dancing became a way for young people to connect through bodies rather than words – and techno in Berlin provided a clean canvas for young people to feel part of society in a way that perhaps politics did not.

Rise of the ‘Easyjetset’

The enthusiasm and dedication of some of the social entrepreneurs from the 1980s and 1990s has resulted in a vibrant music scene in Berlin today. In fact, Berlin’s techno scene has become so famous that tourists visit Berlin to not necessarily satisfy their historical interests but to go clubbing – the Easyjetset.

Read more:

This development has allowed Berlin to market itself as the “capital of techno”, showing the value that both tourists and the Senate of Berlin assign to electronic music in the city. It is further evidenced in the way that the city tries to save some of its unique (sub)cultural spaces through subsidies, something that London is failing to do.

Many of the people who organised parties and concerts back then have become important social and cultural commentators and contributors to the culture of the city and beyond. For example, Mark Reeder, who organised the illegal concerts of Die Toten Hosen in the 1980s, which created opportunities for young people in East Berlin to congregate and express themselves, continues to work in the city as label owner (MfS) and cultural commentator.

Dimitri Hegemann gave us the famous Tresor nightclub. The techno music that Tresor championed, is now considered to have provided the soundtrack for German unification. Hegemann is an influencial international cultural commentator and entrepreneur who continues to develop interesting projects that benefit the city as well as rural Germany.

Unification is complete on the Berlin dance floors. Berliners and tourists benefit from this coming together of creative energy, enthusiasm and dedication. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if music managed to unite the rest of the country in a similar way?

Beate Peter, Senior Lecturer, German, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

11.11.19

War is ignorance

If you can't bear to watch the video you might like to listen to the original tune that inspired the making of the video and is its soundtrack:

Meet the artist turning seafront rubbish into art for Portsmouth exhibitions

Now, one woman has vowed to do her bit for the environment by turning rubbish into works of art. Candy uses plastics found on the seafront to create ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

8.11.19

New play from the writer of Rocketman explores the power of art

New play from the writer of Rocketman explores the power of art ... the prejudice they faced to eventually take the British art establishment by storm.

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

6.11.19

5.11.19

British Museum is world's largest receiver of stolen property, leading human rights lawyer claims

Robertson criticises the British Museum in particular for allowing an unofficial ”stolen goods tour” that “stops at the Elgin marbles, Hoa Kakananai'a, ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

4.11.19

3.11.19

Ken Loach's new film on the gig economy tells exactly the same story as our research

Ricky, from Sorry We Missed You.

Joss Barratt/Sixteen Films

Robert MacDonald, University of Huddersfield

Ken Loach’s film, Sorry We Missed You, tells the harrowing tale of Ricky, Abby and their family’s attempts to get by in a precarious world of low paid jobs and the so-called “gig economy”.

But how realistic is it? Can Loach’s film be accused of undue pessimism? After all, UK government ministers have applauded the gig economy and the freedom and flexibility of being an “everyday entrepreneur”.

A new study by myself and employment expert Andreas Giazitzoglu investigates what we know about the gig economy, in order to get a clearer picture of what is really going on in the contemporary world of work in the UK.

Narrowly conceived, the gig economy means workers (as independent contractors) doing discrete, short-term tasks – or “gigs” – for companies via digital platforms such as Deliveroo, Amazon or Uber. As one study describes them, these are “labour contracts that are as temporary as is possible for them to be”.

We argue that it is better to see the gig economy as part of a wider shift towards insecure forms of work. Long-term unemployment is no longer a serious social policy problem, but standard, full time, long-term employment is also much less common.

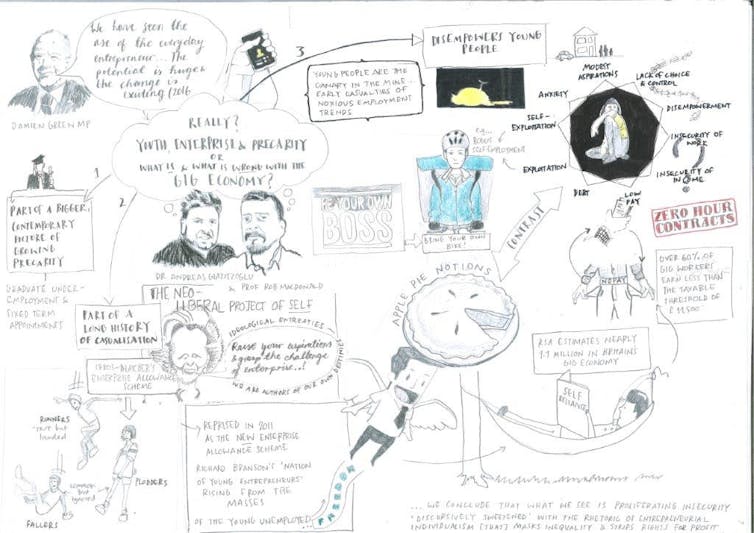

Our study in illustrated form, by Dr Cheryl Reynolds, University of Huddersfield.

Dr Cheryl Reynolds, Author provided

More and more people are churning from “one shit job to another shit job”, as Ricky puts it in Loach’s film, punctuated with periods of unemployment. And as Loach observed (in a Q&A session following a preview), Sorry We Missed You is a sequel to the 2016 film I, Daniel Blake, which explores the degradations of the UK’s benefit system.

These are two sides of the same coin, as research on “the low-pay, no-pay cycle” has shown. Many of these jobs are on zero-hours contracts, which although illegal across much of the EU, have boomed in the UK.

Read more:

We showed I, Daniel Blake to people living with the benefits system: here's how they reacted

There were fewer than 200,000 of these contracts in 2007. Ten years later, in 2017, there were over 1.8m.

Employers insist that workers want this “flexibility”. But two-thirds would prefer a fixed-hours contract.

Degraded work conditions

The government celebrates high levels of employment but two-thirds of employment growth since the 2008 financial crash has been in self-employment or other forms of “atypical work”. Much of this self-employment appears to be bogus. Just like in Sorry We Missed You, employers designate workers as “independent contractors” to cut wage costs and employment rights

Investigative journalism has exposed the degraded work conditions of “self-employed” delivery drivers like Ricky: intense pressure to meet delivery schedules, breaking speed limits, snatching meals on the run, urinating into plastic bottles rather than stopping, barely making the national minimum wage.

Even a government inquiry found that “some companies are using self-employed workforces as cheap labour”, damaging workers’ well-being in order to “increase profits”.

If not bogus, then much self-employment is likely to be “forced”, perceived as the only alternative to being unemployed. This was typical of the “young entrepreneurs” I interviewed in the 1980s.

Held up as role models for Margaret Thatcher’s “enterprise culture”, their ambitions were, in fact, much more prosaic. Rather than go on the dole, they used the (recently re-launched) Enterprise Allowance Scheme to set up “micro-businesses” – knitting jumpers, repairing bicycles, freelance photography – keeping going by undercutting other businesses and by gross self-exploitation. Very few succeeded over the long term.

Most plodded along until, exhausted, demoralised and in debt, they closed down their businesses. Low pay is also typical of more recent forced self-employment and has been a key factor in the UK’s shift towards low paid work.

Across the research, we found ten things that were common to workers’ experiences of this new, insecure labour market:

- Modest aspirations (people were not looking to get rich quick but wanted regular work and to be able to pay the bills)

- Lack of choice

- Disempowerment (employers now have “disciplinary discretion” to withhold offers of work to people on zero-hours contracts)

- Insecurity of work

- Insecurity of income

- Low pay

- Debt

- Exploitation

- Self-exploitation

- Anxiety

One of the duties of critical social science is to question fashionable ideas. We should be particularly alert when comfortably placed, middle-aged politicians exhort younger people to “take up opportunities” that they themselves would never dream of going near.

Would government ministers be quite so “excited” about the gig economy if they had to surrender their fixed salaries, paid holidays and pension schemes in favour of working a daily schedule so gruelling that toilet stops are impossible and the minimum wage cannot be earned?

All of us – the public who rely on the services of the gig economy just as much as the politicians who proclaim its virtues – need to wake up to the reality that, in this instance, “flexibility” is just another word for exploitation.

Robert MacDonald, Professor of Education and Social Justice, University of Huddersfield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

2.11.19

Remembrance poppy art at the VC Gallery

THE VC Gallery in Haverfordwest is currently home to some spectacular Remembrance-themed art. The art has been created by the Haverfordwest ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Raqib Shaw’s bonsai tips - ‘not a good idea to have an active social life' 🌳 | Tate

Watch the full video of Raqib Shaw's studio tour: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtKLOWxXV6U View on YouTube