27.7.23

Why haven't I heard of the artist Hilma af Klint? | Tate

View on YouTube

25.7.23

Actors are really worried about the use of AI by movie studios – they may have a point

Film and television actors in the US came out on strike on July 14, causing Hollywood productions to shut down. The action has also had an impact on US films shooting in the UK: director Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice 2 has “paused” and the production of Deadpool 3, filming at Pinewood Studios with stars Ryan Reynolds and Hugh Jackman, has been stood down.

The dispute is about remuneration for actors, very few of whom enjoy the high income of Hollywood stars. But an additional argument between the union, SAG-AFTRA, and film producers is about the use of artificial intelligence (AI). Actors are fearful of the impact of AI on their careers.

When they perform on film sets, their image and voice are digitally recorded at extremely high resolution, providing producers with huge amounts of data. Actors are concerned the data can be reused with AI. New processes such as machine learning – AI systems that improve with time – could turn an actor’s performance in one movie into a new character for another production, or for a video game.

Actors feel an urgent need to control how AI manipulates their image. The union president, Fran Drescher, says: “We are all in jeopardy of being replaced by machines.” But how realistic are these fears?

‘Synthetic media’

When we talk about the use of AI in film and television, there are multiple techniques under development. We categorise these as “synthetic media”. This covers processes such as deepfakes, voice cloning, visual effects (VFX) created using AI, and completely synthetic image and video generation.

I have written before about deepfakes for The Conversation, pointing out the benefits as well as dangers. For screen actors, deepfakes are one of the most vivid threats.

This is because, since machine learning took off, Hollywood stars including Scarlett Johansson and Gal Gadot have found their faces deepfaked into porn movies. This is a major gender-based issue: it’s almost always female actors whose images are manipulated and used in this way.

We tend to think of artifical intelligence as omnipotent. But my research has found that integrating deepfakes into the language of cinema and TV drama is difficult. Certain shot types are easy, such as front-on long shots, but asking the AI to produce a profile shot tests the algorithm to its limit.

Industry research and development (R&D) programmes such as Disney Research have invested a huge amount of effort into perfecting deepfake techniques. But no one has yet produced an easy way to swap an actor’s face into any shot size or angle that the director chooses, with convincing, high-definition results.

Background actors

The actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA, is particularly concerned about background actors – or “extras” – being exploited by producers using AI manipulation. In the union’s special agreement for background actors, which lists the additional payments that they should receive, there is currently nothing stated about the AI use of recorded footage – the arrival of new technology necessitates a negotiated deal with the producers.

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) claims to have made a “groundbreaking AI proposal which protects performers’ digital likenesses, including a requirement for (a) performer’s consent for the creation and use of digital replicas or for digital alterations of a performance”.

However, the actors’ union boss Duncan Crabtree-Ireland retorted: “They proposed that our background performers should be able to be scanned, get paid for one day’s pay, and their companies should own that scan – their image, their likeness – and should be able to use it for the rest of eternity in any project they want, with no consent and no compensation.”

Ethical dimension

This month, I convened a meeting at the University of Reading, in which academics, stakeholders and creative producers came together to discuss the issues of AI in screen production. We have formed the Synthetic Media Research Network, a group that wants to see strong ethics built into the exciting new opportunities that AI brings to the screen industries.

Philosophers, lawyers, ethicists and trade unionists joined the discussion, because establishing a values-based system for how AI can change performers’ images and identities is a fundamental issue for the film and TV industries.

When I talked to Liam Budd, national officer for the UK actors union, Equity, he said: “If you’re going to exploit our members’ work using AI tech, you have to get consent from them and many members won’t want to.” Currently, there is no nationally agreed system regulating how performers give consent for the use of AI on their image.

Actors will want to be persuaded that the extra pay they receive makes it worthwhile – or they want the right to opt out on a job-by-job basis. The current situation is that actors feel obliged to sign away their rights “in all media” and “in perpetuity”.

Dr Mathilde Pavis, an expert on AI rights and intellectual property, says: “You can’t ask all of this from people without either remuneration or something in return, and at the moment that’s being added on to their contracts without more given in return.” The lack of agreed terms has led to Equity launching a campaign called Stop AI Stealing the Show.

Last week, the union also held rallies in Manchester and London in support of their striking counterparts in the US. When they began a similar scale of dispute in 1980, actors stopped work for three months. Brian Cox, star of Succession, thinks that the strike may last until the end of the year.

Actors are angry that their system of payment has not caught up with the streaming era, with Netflix, Amazon and Disney repeat screening their work while paying little in the way of royalties.

But fear is the stronger emotion here: AI is a new technology that sparks deep and legitimate fears for screen actors. Will they be “replaced by machines” as the union president has said? Unless they can be reassured about their future, American actors will not be returning to the studios soon.![]()

Dominic Lees, Associate Professor in Filmmaking, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

24.7.23

Virginia Woolf’s copy of her first novel was found...

Virginia Woolf’s copy of her first novel was found in a University of Sydney library. What do her newly digitised notes reveal?

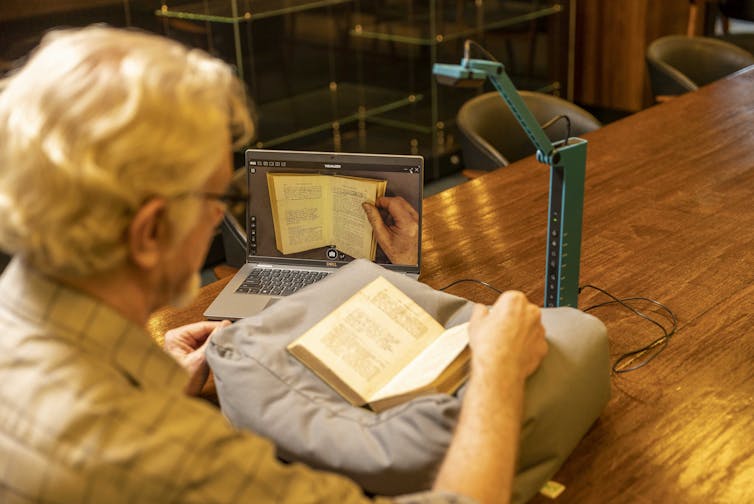

One of just two copies of Virginia Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out (1915), annotated with her handwriting and preparations to revise it for a US edition, was recently rediscovered in the Fisher Library Rare Books Collection at the University of Sydney.

Purchased in the late 1970s, it had been misfiled with the science books in the Rare Books collection. Simon Cooper, a metadata services officer, found it in 2021 and immediately understood the value of his discovery.

The Sydney copy, which is the only one available for the public to view, has now been digitised. It’s available online – allowing scholars and readers to study and consider Woolf’s editorial interventions.

The Voyage Out follows Rachel Vinrace and a mismatched collection of characters embarking on her father’s ship to South America. Woolf’s story grapples with self-discovery and satirises Edwardian life.

It almost finished her writing career. She struggled through years of drafts, eventually abandoning the first version in 1912: it was titled Melymbrosia, named after the food of the Greek gods. Woolf’s ideas on colonialism, women’s suffrage and gender relations were considered too dangerous for a first-time novelist.

Over the next three years, she composed the (retitled) novel we have today, published by her half-brother Gerald Duckworth in London in 1915. At this pivotal moment, she began her diary and suffered a significant mental breakdown, losing the rest of the year to illness.

In preparation for the novel’s first US edition, published by George H. Doran in New York in 1920, Woolf carried out a series of revisions to her text. Two copies of the first UK edition of the novel contain the evidence of this process, with Woolf’s handwritten annotations and typed page fragments pasted into each book.

Why revise?

What motivated Woolf to revise her text? She made revisions in the aftermath of her breakdown, and after her literary career was revived with her second novel, Night and Day, published in 1919.

Scholars have suggested she wished to place some distance between her own psychological stresses and the anguish of her primary character, Rachel Vinrace. Both Woolf and her chief protagonist had domineering father figures, had lost their mothers at a relatively young age, and were denied a formal education – instead being schooled at home. Laying out her character’s mental life so starkly caused Woolf some discomfort. A new edition may have provided an opportunity to reconsider.

This is a plausible theory. But does the evidence in Woolf’s corrections bear it out? There are two main places in the text where the majority of changes are indicated: both are pivotal moments in the narrative.

The first set of changes occurs in Chapter XVI, where the conversation between Vinrace and Terence Hewet – the pair occupying the romantic plotline of the novel – is altered to reduce access to Rachel’s inner thoughts. Entire paragraphs are replaced by typed text pasted directly onto the page, where the narrator studies Rachel without the guarantee of understanding her.

This has the effect of diluting some uncomfortable autobiographical elements in the text, but also marks a significant shift in the way narration accesses the minds of characters.

The narrator is bounded by the limits of character itself: the depths of Rachel’s subjectivity are unknown even to her. This bears the mark of modern psychology and Freud’s theory of the unconscious, in the years before and during the composition of the novel.

A modernist revolution

This innovation signals a profound shift in modernist fiction, which began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and is characterised by a self-conscious break with traditional ways of writing.

The unknowability of Woolf’s characters begins with the dark regions of the mind. No longer in the realm of realism, where thoughts and actions are knowable (and often transmitted by an omniscient narrator), instead the narrator provides a portrait of the complex modern person, who responds to the world in ways not fully accountable by reason.

The other significant set of revisions in the Sydney text arise in Chapter XXV, in which Rachel and Terence attempt to navigate the future of their nascent relationship – which also marks Rachel’s descent into fever and her decline, ending in death.

Long passages are marked for deletion (although none were actually deleted in the first US edition). They are largely concerned with Rachel’s fevered consciousness and Terence’s attitudes towards romantic love and its effects on an artistic life.

Woolf again may have wished to put distance between the narrator and the intimate thoughts of her characters, invoking instead a space of ambiguity, where words and gestures are to be interpreted by readers rather than analysed in full light by a knowing narrative consciousness.

Woolf’s first novel straddles the conventions of realism inherited from the 19th century and the new, experimental fiction of the 20th. The Sydney text tells an important part of this story.

It shines a light on Woolf’s developing technique and its evolution into the free indirect style for which she became famous in later novels such as Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse and The Waves.

Woolf was at the centre of the revolution in the novel form during the time of modernism. The evidence is there in her annotated copy of The Voyage Out.![]()

Mark Byron, Professor, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

10.7.23

Discover the work of artist and fisherman Alfred Wallis | Tate

"Art should be for everyone" – Mari Katayama | Tate

Artist Mari Katayama creates hand-sewn sculptures and photographs that prompt conversations and challenge misconceptions about our bodies. B...