A little reminder

27.10.20

25.10.20

Daylight saving time: five tips to help you better adjust to the clock change

Daylight saving time was first implemented during the first world war to take advantage of longer daylight hours and save energy. While this made a difference when we heavily relied on coal power, today the benefits are disputed. In fact, emerging research suggests that moving the clocks twice a year has negative impacts, particularly on our health.

During the first days after the clocks change, many people suffer from symptoms such as irritability, less sleep, daytime fatigue, and decreased immune function. More worryingly, heart attacks, strokes and workplace injuries are higher during the first weeks after a clock change compared with other weeks. There’s also a 6% increase in fatal car crashes the week we “spring forward”.

The reason time changes affect us so much is because of our body’s internal biological “clock”. This clock controls our basic physiological functions, such as when we feel hungry, and when we feel tired. This rhythm is known as our circadian rhythm, and is roughly 24 hours long.

The body can’t do everything at once, so every function in the body has a specific time when it works best. For example, even before we wake up in the morning, our internal clock prepares our body for waking. It shuts down the pineal gland’s production of the sleep hormone melatonin and starts releasing cortisol, a hormone that regulates metabolism.

Our breathing also becomes faster, our blood pressure rises, our heart beats quicker, and our body temperature increases slightly. All of this is governed by our internal biological clock.

Our master clock is located in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. While all tissues and organs in the body have their own clock (known as a peripheral clocks), the brain’s master clock synchronises the peripheral clocks, making sure all tissues work together in harmony at the right time of the day. But twice a year, this rhythm is disrupted when the time changes, meaning the master clock and all the peripheral clocks become out of sync.

Since our rhythm is not precisely 24 hours, it resets daily using rhythmic cues from the environment. The most consistent environmental cue is light. Light naturally controls these circadian rhythms, and every morning our master clock is fine-tuned to the outside world.

The master clock then tells the peripheral clocks in organs and tissues the time via hormone secretion and nerve cell activity. When we artificially and abruptly change our daily rhythms, the master clock shifts faster than the peripheral clocks and this is why we feel unwell. Our peripheral clocks are still working on the old time and we are experiencing jetlag.

It may take several days or weeks for our body to adjust to the time change and for our tissues and organs to work in harmony again. And, depending on whether you are a natural morning person or a night owl, the spring and autumn clock change might affect you differently.

Night owls tend to find it more difficult to adjust to the spring clock change, whereas morning larks tend to be more affected by the autumn clock change. Some people are even entirely unable to adjust to the time change.

While any disruption to our circadian rhythm can affect our wellbeing, there are still things we can do to help our body better adjust to the new time:

Keep your sleeping pattern regular before and after the clocks change. It’s particularly important to keep the time you wake up in the morning regular. This is because the body releases cortisol in the morning to make you more alert. Throughout the day you will become increasingly tired as cortisol levels decrease and this will limit the time change’s impact on your sleep.

Gradually transition your body to the new time by changing your sleep schedule slowly over a week or so. Changing your bedtime 10-15 min earlier or later each day helps your body to gently adjust to the new schedule and eases the jetlag.

Get some morning sunlight. Morning light helps your body adjust quicker and synchronises your body clock faster – whereas evening light delays your clock. Morning light will also increase your mood and alertness during the day and helps you sleep better at night.

Avoid bright light in the evening. This includes blue light from mobile phones, tablets, and other electronics. Blue light can delay the release of the sleep hormone melatonin, and reset the internal clock to an even later schedule. A dark environment is best at bedtime.

5) Keep your eating pattern regular. Other environmental cues, such as food, can also synchronise your body clock. Research shows light exposure and food at the correct time, can help your master and peripheral clocks shift at the same speed. Keep mealtimes consistent and avoid late-night meals.

Following a Europe-wide consultation, in March 2019 the European Parliament voted in favour of removing daylight saving time – so this might be one of the last times many European readers have to worry about adjusting their internal clocks after a time change. While member states will decide whether to adopt standard time (from autumn to spring) or daylight saving time (from spring to autumn) permanently, scientists are in favour of keeping to standard time, as this is when the sun’s light most closely matches when we go to work, school, and socialise.![]()

Gisela Helfer, Senior Lecturer in Physiology and Metabolism, University of Bradford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

21.10.20

Dylan Thomas: ‘lost’ fifth notebook reveals how the great Welsh poet changed his style

It’s the dream of every researcher to get their hands on a hitherto-unknown manuscript by the author in whose work they specialise. As you’d imagine, most never realise that dream. But on December 9 2014 at Sotheby’s auction house in London, I was lucky enough for it to happen to me. A school exercise book that had once belonged to Dylan Thomas, filled with 16 of his poems in his handwriting, was bought by my then-employers, Swansea University, for £85,000 and given to me to edit.

A PhD student, Adrian Osbourne, was funded to help me in my labours. A greater honour, and a more daunting, more thrilling task, would have been hard for either of us to imagine.

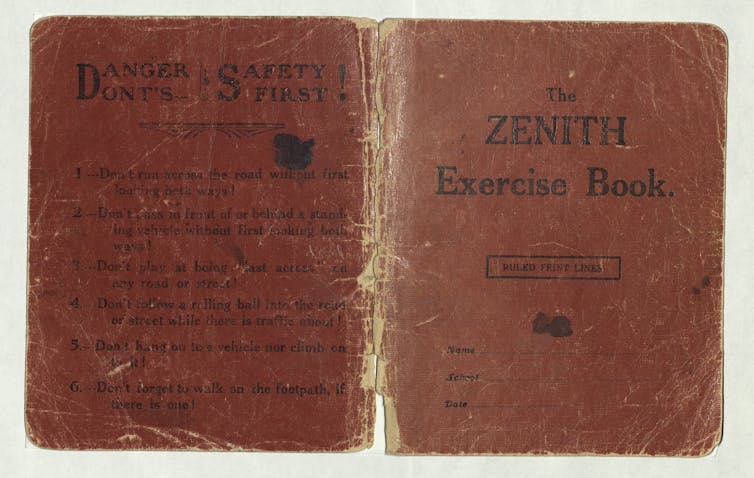

To begin at the beginning, however, some context. From April 1930, aged 15, Thomas began copying his completed poems into a series of school exercise books. In his short story, The Fight, the “D. Thomas” character notes how: “In the evening, before calling on my new friend, I sat in my bedroom by the boiler and read through my exercise-books full of poems. There were Danger Don’ts on the backs.”

In a letter of 1933, Thomas referred to an “innumerable” number of such notebooks. And, unlike most poets, he hung onto his juvenilia, carrying them around with him and raiding them for material until 1941. At that point, in the darkest days of the second world war, hard up and with a family to support, he sold the first four, which run from April 1930 to April 1934, to the library of the State University of New York at Buffalo. Scholars were given access to them and they were published in 1967 as Poet in the Making: The Notebooks of Dylan Thomas.

No more notebooks emerged during Thomas’s lifetime, nor – despite much speculation – did any appear after his death in 1953. Thus, the Sotheby’s notebook is the only one to have appeared, and it covers the period summer 1934 to August 1935 – making it a direct continuation of the first four.

Scrap paper?

The fifth notebook’s extraordinary nature as an object is matched by the story of its survival. Two notes contained in the Tesco’s bag in which the notebook was found allowed us to establish this. The first, a brief description by Thomas himself, shows that the last time he was in possession of it was early 1938.

After marrying in summer 1937, he and Caitlin Macnamara lived with Caitlin’s mother at her home in Hampshire until early 1938. The second note – by Mrs Macnamara’s maid, Louie King – revealed that after Dylan and Caitlin’s departure she was given the notebook, with other “scrap paper” they left behind, to burn in the kitchen boiler. King, however, withheld the notebook from its fiery fate – out of curiosity, sentiment, or for some other reason we know nothing about. When she died in 1984 the notebook passed to her family, who kept it, still a secret to the outside world, until 2014.

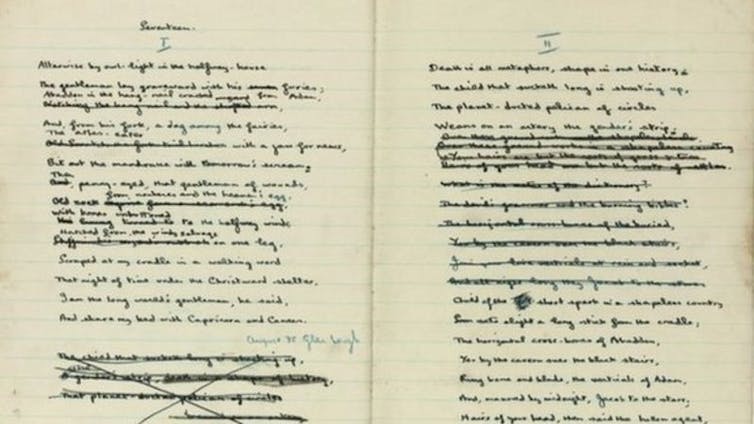

We now had three tasks – to transcribe the notebook poems, deciphering, if possible, Thomas’s many corrections and deletions. We then set out to compare them with the published versions and to work out what light – if any – they shed on Thomas’s poetic development.

It should be said that the fifth notebook poems are all published ones. Unlike its predecessors it contains no unpublished items (this may be why Thomas does not seem to have minded losing it). Where it differed was in the number of corrections it contained. The poems in the first four notebooks are almost always clean copies. In the fifth, many poems undergo radical revision, allowing us to trace Thomas’s creative processes at first hand.

Luckily, we were able to realise most of our aims. Thomas’s handwriting is clear, so most poems and corrections were easy to read. Some problems arose as the notebook progressed, and the poems grew more complex and worked-over. Usually, educated guesswork (not to mention my colleague’s keen eyesight) carried us through – although in a handful of cases we called in a technician armed with a super-photocopier. In the end only five words were unresolved.

Changing style

Among the deleted passages were many of great beauty and originality, some of which Thomas reworked elsewhere. There were also three stanzas, in two of the poems, which had never been seen before.

Everywhere his incredibly rapid development as a poet was evident. Sometimes, even the tiniest item could alter our understanding of a poem; in I Dreamed My Genesis, the notebook confirmed that a comma should replace a full stop found in three print editions, making better sense of eight lines of the poem.

At the other end of the scale of significance, after poem eight, When, Like a Running Grave, we noted that Thomas had, unusually, written out the date in full: “26th October 1934” – the eve of his 20th birthday – with an emphatic line in the centre of the page. We know from the number of poems he wrote about birthdays (they include Poem on His Birthday and Poem in October) that they held great significance for Thomas. So we feel it is no coincidence that the poems that follow this point, beginning with Now and culminating in Altarwise By Owl-Light, the final poem, differ from these before it, and are the most experimental he ever wrote. Agonisingly aware of human mortality, of the end of youth, this emphatic dating marks the exact moment of Thomas’s momentous decision to adopt a more daring style.

The notebook, then, represents a kind of hinge in his early career, and this is something we could only have learned from the notebook itself, since the stylistic shift is completely obscured by the non-chronological order in which When, Like a Running Grave and Now were published. It grants us the privilege of witnessing, for the first time, the young Dylan Thomas at the height of his powers, seizing and reshaping his poetic destiny.![]()

John Goodby, Professor of Arts and Culture, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kids React to Art - Cildo Meireles's Babel | Tate #kidsreact #funnyvideo

📻 We asked kids to react to Cildo Meireles's Babel, one of 25 artworks celebrating Tate Modern's 25th birthday, and this is what th...