A much-loved local landmark with an ancient fort at its summit, Tap O'Noth is a gently sloping hill overlooking the lush rolling farmland around the village of Rhynie in Aberdeenshire.

Until now, the fort was widely believed to date back to the Bronze or Iron Age. But thanks to a combination of drone footage, aerial 3D laser-scanning and radiocarbon dating, our research has revealed that not only is the fort much younger than previously thought, it also potentially stands as one of the largest Pictish settlements of the late and post-Roman periods.

We discovered it had once contained 800 dwelling platforms – housing as many as 4,000 people – and if they all date to the same period this would stand as almost urban-scale settlement, which archaeologists previously did not believe existed in Scotland until the 12th century.

Uncovering the Picts

The fearsome Picts were first mentioned in Late Roman sources as a collective name for the barbaric peoples living north of the Roman frontier in northeast Scotland. The Pictish kingdoms went on to dominate a large part of Scotland until the late first millennium AD, but few sources have been left behind to help understand this important period.

The University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts project was established in 2012 to find new sites in a period with few identified locations either in written sources or the archaeological record. A key focus has been the area around the village of Rhynie, whose name includes a form of the Celtic word for “king”, rīg.

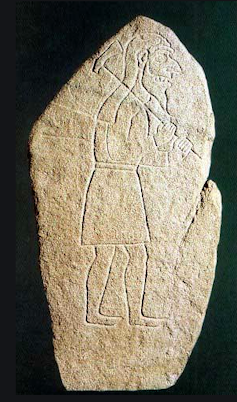

Our work at the site suggests the Rhynie valley was an elite Pictish centre from the 4th-6th centuries AD. The area has long been known for its concentration of Pictish stones carved with symbols. In March 1978, a farmer ploughed up a spectacular stone known as the “Rhynie Man” in a field on Barflat Farm just to the south of the modern village.

That summer the local council’s archaeology department took aerial photographs of a series of enclosures around the Craw Stane, below, another Pictish stone that still stands in the same field where the Rhynie Man was found.

Our excavations around the Craw Stane at Barflat farm from 2011-2017 found that this stood towards the entranceway of a settlement that included the remains of timber buildings enclosed by ditches, banks and an elaborate wooden wall made of oak posts and planks.

The excavations revealed a rich array of finds including shards of Late Roman wine amphorae (earthenware jars) imported from the eastern Mediterranean, shards of glass drinking beakers from France, and one of the largest collections of metalworking from early medieval Britain. This includes moulds and crucibles for making pins, brooches and even tiny animal figurines that match the animals carved on Pictish stones.

An iron pin shaped like the axe carried by the Rhynie Man was also discovered, a remarkable find that was one of a number of objects that could be linked directly to the iconography of these stones. The axe that the Rhynie Man carries appears to be a form associated with animal sacrifice and the fearsome figure on the stone may be a pagan deity associated with cult practices.

Our excavations on the outskirts of the village, a few hundred metres north of the Barflat site, also found traces of a contemporary cemetery and uncovered the remains of Pictish burial mounds including the partially preserved remains of an adult female.

A stunning discovery

We have been investigating the wider area of the Rhynie valley since 2017, targeting a number of hillforts found overlooking the Barflat complex. But Tap O'Noth is the most compelling site and one of the most spectacular hillforts in Scotland. The second highest in the country, it is one of the best examples of a vitrified fort – vitrification being the result of the destruction of timber-laced ramparts by fire.

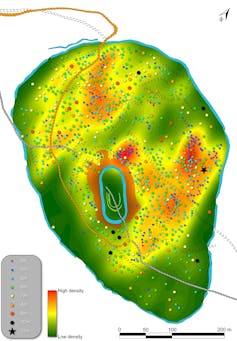

The summit fort is surrounded by a massive 16-hectare enclosure, which itself represents the second largest hillfort in northern Britain. Within the larger fort hundreds of house platforms had been recorded in earlier surveys.

Our excavation of the oblong fort was an exercise in extreme archaeology with the vitrified walls and areas of the interior tackled over two gruelling seasons. It revealed the buckled and heavily burnt wall-faces of the vitrified fort and radiocarbon sampling showed it dated to the period 400-100 BC in the Iron Age.

The results from the larger fort then were all the more surprising and exciting. Due to its size and elevation scholars have suggested its construction and occupation dated from a time when the climate was warmer, possibly during the Bronze Age.

But our most recent excavations in 2019 turned that notion on its head – with radiocarbon dating from two platforms and the rampart spanning the 3rd to 6th century AD period, dates broadly contemporary with the Barflat complex. LiDAR scanning (essentially 3D laser scanning from a plane) and our drone photogrammetry survey also suggests that many more house platforms are contained within the lower fort – perhaps as many as 800 – making Tap O’ Noth potentially one of the most densely occupied hillforts in Britain.

The rampart belongs to the latter part of that span of radiocarbon dates, making it the largest hillfort of that date we know in Britain. The number of house platforms on the site suggest a very large population, though we need to test more platforms to assess if they are contemporary, but there is little in an early medieval context to compare the site to.

Our work in the Rhynie valley gives us an unexpected and unparalleled insight into a possibly early royal landscape of the Picts of the 4th-7th century AD. The exciting Tap O’Noth discovery in particular has the potential to shake the narrative of this whole time period.![]()

Gordon Noble, Professor of Archaeology, University of Aberdeen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments