28.8.22

Lost painting by Britain’s leading female abstract artist rediscovered

26.8.22

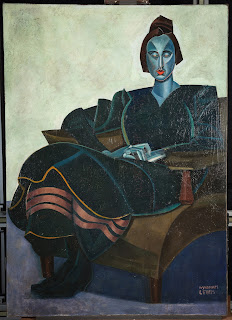

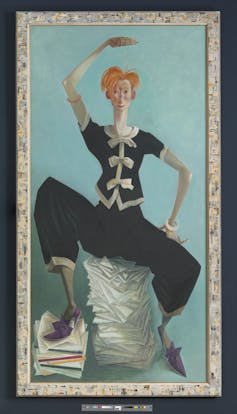

Why John Byrne is one of Scotland’s greatest artists

A Big Adventure, John Byrne’s retrospective at Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery, offers a fascinating insight into the breadth of skills of one of Scotland’s best-known creative forces.

During an illustrious career he has traversed a number of cultural genres with success as an artist, playwright and scriptwriter with many stage and TV hits. Over the last 60 years he has built up an impressive catalogue of outstanding creative works that have become part of the Scottish cultural landscape, gaining him international recognition. Now in his eighties, Byrne is still painting and writing plays, his desire to create still burning fiercely.

The exhibition includes portraits of actors and musicians including many self portraits, figurative works, illustrations, cartoons, album covers, films and promotional material. He has worked in all sizes and mediums from thumbnail storyboarding to full gable-end murals on tenement buildings.

As a researcher looking into the lives of contemporary artists in a culturally dynamic Scotland, the show has given me unique insights into the distinctly Scottishness of Byrne’s work, approach and dedication to his craft.

Humble beginnings

Growing up in Ferguslie Park, Paisley, in one of the most deprived areas in Scotland, you would expect Byrne’s work to be deeply marked and influenced by that experience. However, there is rarely any sign of darkness or trauma in his artworks; in fact, his art is often joyful, displaying a gentle playfulness.

Byrne struggled to make a living as an artist after leaving Glasgow School of Art in 1963, and after a few years he decided to create an alter-ego called “Patrick”. Under this name he submitted some primitive-style artwork to the Portal Gallery in London which he pretended was painted by his father. It was accepted and exhibited in 1967, kicking off Byrne’s professional artistic career down south.

He progressively developed his writing skills in the 1970s to the point his artistic output declined and he became fully immersed in the world of scriptwriting and theatre. In this transitional period, he worked with both visual images and written dialogue as part of a fascinating creative process where his character ideas were visually illustrated and then allowed to mature and take form, before developing their own authentic voices.

The play and scriptwriting successes of Writer’s Cramp (1976), Slab Boys (1978) – based on his own experiences working in a carpet factory in the 1950s – Tutti Frutti (1987) and Your Cheating Heart (1990) interrupted a developing artistic career which was sidelined for 20 years. But he continued to produce powerful graphics and illustrative work supporting and promoting his plays and works for television.

A polymath talent

How can this extraordinary talent be summed up? Byrne is a figurative artist whose work is grounded in his exploration of the human experience which can be seen at the centre of both his scripts and his visual artworks.

In the early 1980s, a group of young painters called the New Glasgow Boys (referencing the influential late-19th century modern painters the Glasgow Boys) also achieved international success as figurative painters, building upon Byrne’s own artistic output exploring the Scottish working-class psyche.

He is an architect and creator of narratives exploring deeply human characters and their complex relationships, capturing specific periods in time from a very Scottish perspective, as in the working-class characters in the Slab Boys and the rough and ready Majestics band in Tutti Frutti.

Even in his portraits, where he wrestles to understand both himself and the personalities who sit for him, we are given insight into a deeply personal journey. His portraiture is often comedic, and full of playfulness and irreverence, particularly when it comes to his own image.

The 40 self-portraits which dominate the show are larger than life, often set within city and seascapes, using a variety of mediums and nearly always showing him holding his trademark roll-up, a curl of smoke hanging in the air. In his earlier works, such as Self-portrait with Red Palette (1975), they can be serious and melancholic, and later on, full of humour where he does not take himself too seriously. But in more recent works, such as Big Selfie (2014), for example, darker traits reveal themselves, as Byrne muses on mortality and his image as the ageing artist.

In Byrne’s portraits, he treats his sitters with varying levels of respect, from the comic and affectionate, to the deeply serious and more reverent. This is expressed in his varied use of media such as flat oil paint, scraperboard, pastel, water colour and prints. To me his Conté crayon drawings of his daughters, Celia Asleep (1973) and Rebecca (2010), resemble the sketches of Leonardo.

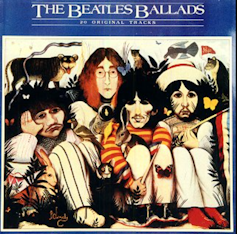

His love of R'n'B and rock'n'roll, together with his close friendships with musicians and actors drove his early artworks through album cover designs, paintings, portraits and caricatures.

His covers include the Beatles Ballads album as well as work for Gerry Rafferty, Stealer’s Wheel and Billy Connolly, whom Byrne has painted several times. His visit to Los Angeles with the singer Donovan had a significant impact, inspiring watercolour studies such as the gentle Burnt Orange LA (1971), and larger scale paintings of black musicians which were exhibited in Glasgow on his return.

His fascination with black musicians has seeped into his artistic fantasy lands including Messiah (2015), a tryptic of musical figures in a fictional American city. And his ongoing relationship with teddy boy and rockabilly culture is reflected in the quiffed Fegs of Underwood Lane, his most recent and current play. It tells a story of a young skiffle band trying to make it big, and involves the big issues of love, religion, sex and death, written in memory of Gerry Rafferty, a close friend who also grew up in Paisley.

This retrospective highlights the quintessential Scottishness of Byrne’s work, in his resilience, his enduring humour and his focus on the frailty of human experience often lived on the edge of working-class communities. It is a richly rewarding show which underscores John Byrne’s rightful place as one of Scotland’s finest and most prolific artists.![]()

Blane Savage, Lecturer in Creative Media Practice and New Media Art, University of the West of Scotland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

25.8.22

The Story of Paula Rego’s Painting ‘The Dance’ | Tate

View on YouTube

17.8.22

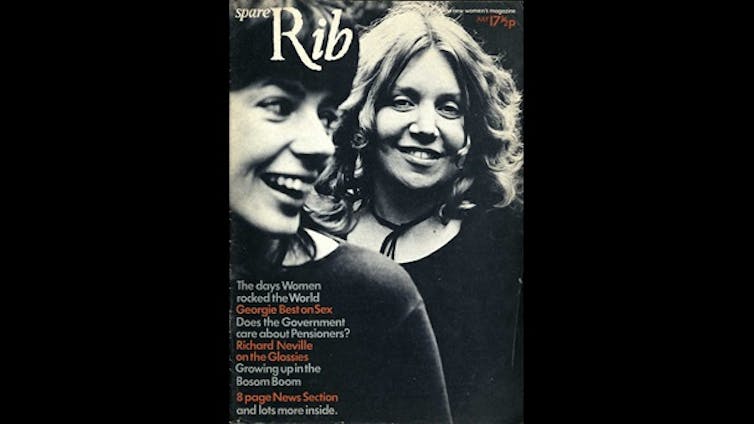

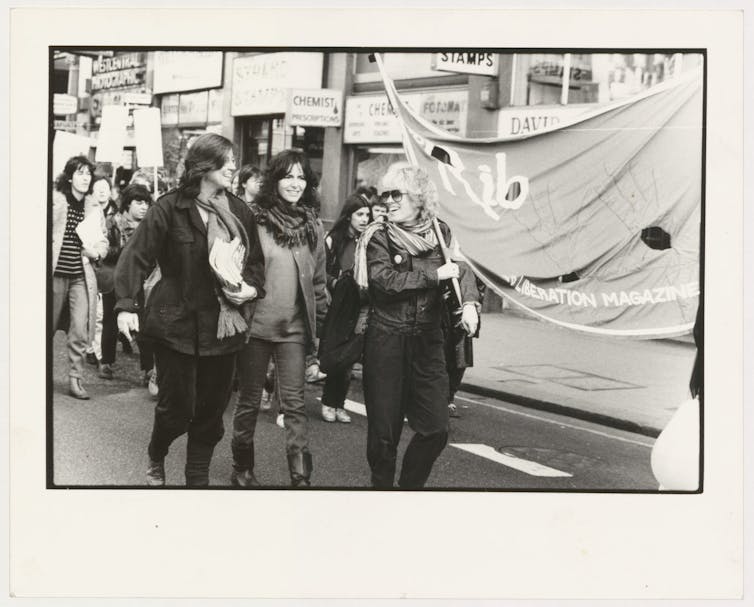

Spare Rib: 50 years

Spare Rib: 50 years since the groundbreaking feminist magazine first hit the streets – its legacy still inspires women

In the summer of 1972, the Women’s Liberation Movement was fighting hard, through rallies and marches, for social, sexual and reproductive liberation. The “second wave” of feminism was at its peak, gaining notoriety after a group threw flour bombs at the Miss World beauty pageant in 1970, highlighting the objectification of women. It hit the news once again in the UK in 1972 when a group of women night cleaners went on strike in London for better working conditions.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone at the time was on board with these women’s claims for equality and the British and American presses often caricatured them as humourless, hairy-legged, bra-burning, unsexed harpies who were set against marriage, families and femininity. To counter the noise of this sort of coverage came the groundbreaking feminist magazine Spare Rib.

With witty coverage and incisive features, the magazine echoed the demands of the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM). The magazine supported campaigns and generally exposed women’s social and cultural experiences of sexism. Spare Rib did all this with captivating journalism and a great sense of humour. The magazine closed in 1993 due to commercial pressures. This year, we celebrate 50 years since its first issue and look back at the legacy it has left behind for feminist media.

A new kind of feminist magazine

The magazine’s founding editors, Rosie Boycott and Marsha Rowe, railed against the sexism and chauvinism of the underground, alternative press, where women were restricted to mundane tasks and excluded from editorial decision-making.

Spare Rib and women’s presses, such as Virago, forged a radically different approach to publishing. Female-led editorial boards enabled open debate of previously taboo subjects such as female orgasm and lesbianism long before these became mainstream concerns. Many feminist magazines operated as collectives and encouraged women to develop publishing skills in the male-dominated profession.

In format and content, Spare Rib crossed boundaries between magazines that focused on home, beauty and lifestyle, such as Woman’s Own, and more overtly political, grass-roots movement media, such as Shrew or Red Rag. In this way, it emphasised both the personal and the political sides of the feminist movement.

In its early days, Spare Rib partially emulated conventional women’s magazines by including articles about cookery, handcrafts and DIY – albeit with a feminist twist and a “can-do” attitude. But it was never conventional in its topics and opinion pieces.

Like Cosmopolitan, which launched the same year in the UK, Spare Rib never shied away from bringing women’s sexuality to the fore. But unlike Cosmopolitan, it also directly addressed sexism in Britain. Spare Rib’s “news pages” kept feminists informed and involved with current protests, updates and achievements. Its lively letter pages also encouraged heartfelt reader involvement.

Over two decades, Spare Rib worked relentlessly for social change, investigating and promoting awareness of serious topics concerning women’s mental and physical health. These ranged from women’s diverse sexuality, home life, domestic abuse, equal pay, sexism in the workplace, female genital mutilation and the refuge movement (which provided safe shelter for battered women) and more. Heightened awareness today of these issues owes much to the campaigning work of those second-wave feminist magazines.

The magazine had a complex relationship with consumerism, navigating an uneasy path between needing advertising revenue but rejecting the sexism of the industry at the time. They did this by trying to advertise ethical products only alongside subscription ads and its own-brand products, such as the Spare Rib diary.

But it struggled to sustain itself with diminishing ad sales and subscriptions. Alongside this, distribution problems and arguments over the direction of the magazine led to its demise and eventual closure in 1993.

The difficulties of representing a movement

From as early as 1982, Spare Rib faced criticism that it was too white, middle-class and London-centric. In 1984, a crisis within the editorial collective revealed that many – including women of colour, Jewish women, Irish women, lesbians and more – felt that Spare Rib, alongside much British feminism, didn’t speak for them or address their particular concerns.

While Spare Rib grappled with diverse identity politics, other feminist magazines spoke directly to different groups. Women’s Voice, founded through the Socialist Workers Party, focused on working-class women.

Mukti: Asian Women’s Magazine, was published by the Mukti collective in six languages and funded by London Camden Council. FOWAAD was a national newsletter for women of African and Asian descent. There were also local feminist publications, such as the Leeds Women’s Liberation Newsletter, which highlighted regional feminist concerns around the UK.

Spare Rib itself became much more international in its feminism too. Recent research on women’s activism around Britain has found that regional feminism and Spare Rib were more far-reaching in their perspective than previously thought.

Innovative, informative, contemporary and political, Spare Rib educated and politicised its readers, galvanising and encouraging feminism in Britain. More than this, it gave women a voice and forum to tell their life stories, enabling them to raise awareness of a myriad of issues.

The self-expression and persuasive writing of Spare Rib have their legacy in feminist media today such as the F-Word, feminist websites such as Everyday Sexism, and online blogs like The Vagenda. Because of its standing in feminist history, Spare Rib has become a touchstone for later feminist magazines, and there was even an attempt in 2013 by Guardian journalist Charlotte Raven to revive Spare Rib itself. Sadly this came to nothing, but the legacy of Spare Rib continues to this day.![]()

Laurel Forster, Reader in Cultural History, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

12.8.22

Afterlives of Slavery in Contemporary Art – The Black Atlantic: Episode 4 | Tate

View on YouTube

11.8.22

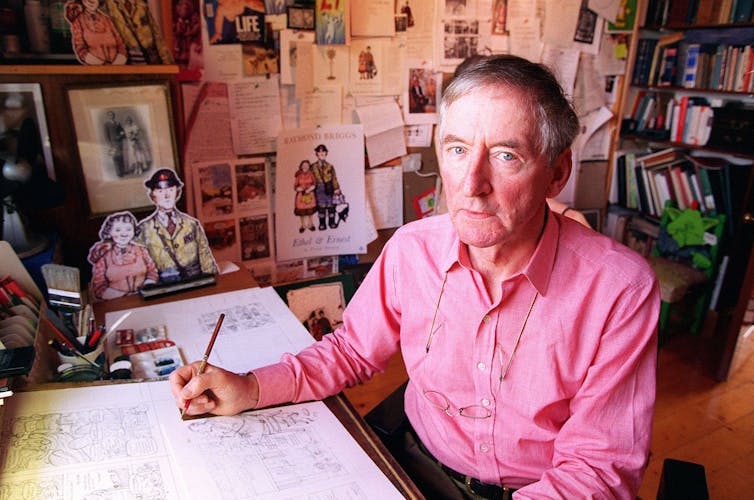

Three Raymond Briggs books that helped make the graphic novel respectable

Raymond Briggs, who died on August 9 aged 88, transformed the way we see and value of the strip cartoon and graphic novel in this country. Briggs’ great achievement was to make the form intellectually respectable through telling stories about seemingly ordinary characters, which were rendered skilfully in the egalitarian medium of coloured pencil.

Born in suburban London in 1939, Briggs had an early ambition to become a cartoonist but this was met with disappointment from his parents, who didn’t see it as a respectable or financially secure choice. After experiencing more snobbery from his teachers at both Wimbledon and Slade art schools, Briggs began his career as a professional illustrator working on conventional children’s books.

The default at the time was to treat words and pictures as separate entities. It wasn’t until the 1960s that he explored his talent and skill to combine both words and pictures, utilising the form of the strip cartoon that defined his future work.

Briggs is best known for his wordless masterpiece The Snowman, published in 1978, essentially a sweet children’s tale. But the loss of his parents Ethel Bowyer and Ernest Briggs in 1971, and his wife Jean Taprell Clark in 1973, imbued an unsentimental directness in his work.

As we mark his passing, it seems fitting that we look at back at three books that each say something quite sweet and poignant about the human condition and elevated the form of graphic novels.

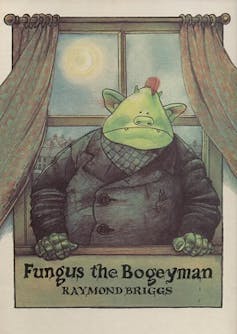

1. Fungus the Bogeyman (1977)

The success of the curmudgeonly Father Christmas and its sequel Father Christmas Goes on Holiday in 1975 established a loyal readership that enabled Briggs time and space to explore more experimental territory, like the wonderfully melancholic nihilism of the children’s book Fungus the Bogeyman published in 1977.

It follows a day (night) in the life of Fungus, a working class bogeyman whose job is to scare humans, as he begins to question the point of his work.

In Fungus, we see Briggs capture the mood of 1970s England through a slimy fairytale. The lights are out. The familiar domestic settings Briggs employs in many of his books is there from the start. Fungus’s wife Mildew rousing her husband in the marital bed: “Time to get up, Fungus my dreary. It’s nearly dark.”

The world-weary introspective musings of Fungus play to young and old readers alike. I recommend reading in slow voice to really get a sense of the wonderful sluggish and downtrodden nature of Fungus: “Oh well, here we go … Off to work again … Onwards always onwards, In Silence and in Gloom.”

It pre-empts both the wave of strikes that would result in Britain’s “winter of discontent” of 1978-79 and the “upside-down” world of the Netflix science fiction series Stranger Things. Briggs flips us, far underground, to the slow, damp, slime of Bogeydom. The world is drawn is exquisite detail employing a cold colour palette of grey greens, muted blues and browns that create its alluring bleakness.

Briggs playfully subverts the graphic convention of the comic strip, drawing in blacked out panels that have apparently been censored by the publisher in the interests of decorum. One such panel declares: “The Publishers wish to state that this picture has been deleted in the interests of good taste and public decency.”

Diagrams, footnotes and an array of asides are “pinned” throughout the story, adding detail and depth to the culture of Bogeydom. One aside, for example, reads: “Bogey umbrellas are upside down. They are designed to catch water and shower it onto the user.” The story is carefully structured, richly detailed and beautifully drawn, unsurprisingly taking Briggs two years to complete.

2. When the Wind Blows (1982)

Briggs resurfaced in 1982 with the politically charged, cold war graphic novel When the Wind Blows, further developing the characters of Jim and Hilda Bloggs from his 1980 book Gentleman Jim.

Briggs was inspired by the absurd and outdated Protect and Survive public information pamphlet, which had been published by the British government in 1980 to advise the public what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. He used the advice within the book to show how shockingly inadequate it was.

The story sets the horror of a nuclear apocalypse against the domestic backdrop of Jim and Hilda’s retired life in rural England. The warmth and geniality of the old couple’s interactions are punctuated by ominous double page spreads of the impending attacks.

Scale is used to brilliant effect, contrasting the tightly ordered panels framing the couple’s organised home life against spreads of military hardware that break the boundary of the page. The inevitable nuclear explosion obliterates the structure of successive pages, and their lives.

It is graphically stunning, with the following frames bent all out of shape until they return to a stable rectangle punctuated with a Briggsian “Blimey!”. The remainder of the book is bleak and achingly sad, a testament to Briggs’ skill with his pencils, empathetic dialogue and willingness to face finitude head on.

3. Ethel and Ernest (1998)

In the 1990s Briggs turned his attention to his own parents in his graphic memoir Ethel and Ernest. It unflinchingly tells the story of how his working-class parents met, and then raised their only child, Raymond.

Their lives are played out against the social and political upheavals taking place through the middle of the 20th century, including the depression, second world war, the birth of the welfare state, television and the Moon landings.

It is both deeply personal yet typically universal, a loving and unsentimental social history document. The British class system is played out through Ethel’s respectable conservatism and Ernest’s ideological socialism.

Though politically polarised, they are kind and stoic, wanting the best for their son. They died in 1971 within months of each other, their son rendering their end with characteristic directness. How proud and amazed they would undoubtedly have been to see what he achieved. Blimey!

The contemporary American cartoonist Chris Ware, much admired by Briggs, said of comics, “There is a magic when you read an image that you know doesn’t move but you have a sense that something is moving, if not on the page, then in your mind.”

While there are many much loved film and television adaptations of Briggs’ work, it is sitting quietly and patiently with his books where that humane magic can be found.![]()

Matthew Edgar, Lecturer in Visual Communication, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

9.8.22

Toppled Monuments and Hidden Histories – The Black Atlantic: Episode 3 | Tate

View on YouTube

5.8.22

Identity and Nationhood – The Black Atlantic: Episode 2 | Tate

View on YouTube

2.8.22

A Taste for Impressionism | Modern French Art from Millet to Matisse

View on YouTube

1.8.22

What is the Black Atlantic? – The Black Atlantic: Episode 1 | Tate

View on YouTube

Raqib Shaw’s bonsai tips - ‘not a good idea to have an active social life' 🌳 | Tate

Watch the full video of Raqib Shaw's studio tour: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtKLOWxXV6U View on YouTube