Plus, we talk to the Canadian First Nations artist Kent Monkman about his monumental paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; and ...

* The full article is published here...

31.1.20

28.1.20

Show Don't Tell at The Horse Hospital

A 'queer group show' including works by Soft Cell singer Marc Almond could be the last exhibition at Bloomsbury's not for profit Grade II listed arts ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

25.1.20

Free exhibition and workshops in East London celebrate the art of drawing

Led by its founding Director, Professor Anita Taylor, Dean of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design at the University of Dundee, and ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

24.1.20

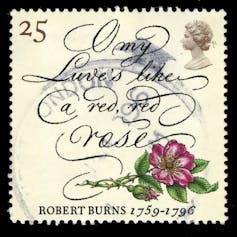

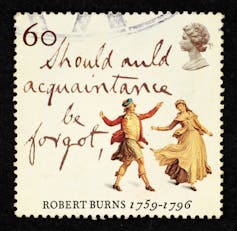

Remembering Robert Burns has never been straightforward

Shutterstock

Gerard Lee McKeever, University of Glasgow

The memory of the Ayrshire-born Scottish poet Robert Burns has always been complicated, especially in Dumfries, the town where he died in July 1796. In the years following his untimely demise at the age of 37, literary tourists including Dorothy Wordsworth and John Keats visited this market town in south-west Scotland in search of their hero. What they found, however, was a vision of Burns and of Scotland itself that seemed out of place, difficult to comprehend and yet intensely personal.

Burns’s own relationship to Dumfriesshire was enigmatic from the start. When he arrived to take up the tenancy of Ellisland farm in the summer of 1788, he declared himself in a “land unknown to prose or rhyme”. But Burns’s view of the region would evolve many times. By August of the same year, he was commemorating the Nith Valley’s “fruitful vales”, “sloping dales” and “lambkins wanton”, and had already written back in October 1787 that: “The banks of Nith are as sweet, poetic ground as any I ever saw.”

Dumfries, where Burns died in 1796.

Shutterstock

Burns composed some of his best-known work during these years, including what many consider his masterpiece, Tam o’ Shanter. And yet a shift in focus from poetry to songwriting – as he worked to collect, revise and compose lyrics for collections of national song – changed the sense of both place and personality in his writing. In his earlier years, Burns’s poetry had often been intensely self-reflective, rooting a version of himself in the Ayrshire landscape where he was raised. Now, his persona receded into the background due to the inherently communal nature of folksong.

At the same time, Burns’s employment as an excise officer and his eventual poor health in Dumfries would lead 19th-century commentators such as the historian Thomas Carlyle to accuse the town of wasting the poet’s talents through a lack of patronage. That underestimates Burns’s agency as a member of the lower middle class, who took pride in supporting his family independently. Yet still, what emerged was a lingering sense of the Ayrshire Burns as the true Burns, where the Dumfries Burns was only a tragic, diminished echo of himself.

Shutterstock

Poetic pilgrimage

In 1803, Dorothy Wordsworth set off from the Lake District on a tour of Scotland in the company of her brother William and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Among key items on their itinerary was a pilgrimage to Burns sites in and around Dumfries. Yet the poet’s memory would not be easily reckoned with.

In her tour journal, Wordsworth quoted Burns’s own A Bard’s Epitaph – “thoughtless follies laid him low, | And stain’d his name” – to underline the moral failings of a poet already famous for his love affairs and heavy drinking. She wrote:

We could think of little else but poor Burns, and his moving about on that unpoetic ground.

Burns proved an inescapable but difficult presence in Dumfries for Wordsworth. He became representative of a south-west Scotland that defied easy comprehension: neither quite “the same as England” nor “simple, naked Scotland”.

Further north at Ellisland farm, Wordsworth remembered catching a view back home to “the Cumberland mountains”. The idea was taken up by her brother in a poem originally titled Ejaculation at the Grave of Burns, in which William imagined himself and Burns as the hills of Criffel and Skiddaw staring at one another across the Solway Firth. Yet the dead poet remained out of reach, leaving these tourists to their personal musings about Dumfriesshire in the terms of tragedy: a visit to Burns in 1803 was already seven years too late.

Keats made a pilgrimmage to Burns’s grave.

Shutterstock

If anything, the situation was even more pronounced in John Keats’s account of his 1818 walking tour, in which Dumfries shoulders much of the blame for the tragic story of this “poor unfortunate fellow”. Keats would find himself disgusted at the tourism industry that had already sprung up at the poet’s birthplace further north in Ayrshire.

But when confronted with the spectacle of Burns’s death, Keats apparently struggled to make much sense of Dumfries at all. Performing a kind of theatrical bewilderment in On Visiting the Tomb of Burns, he wrote that the town seemed “beautiful, cold – strange – as in a dream”.

Memory and imagination

It is difficult to overstate the impact of Burns’s legacy in south-west Scotland, for better or worse. His influence on following generations of poets in the region could be both inspiring and suffocating, while civic pride in his memory took on new forms in Dumfries as elsewhere throughout the 19th century, not least in the extravagant centenary celebrations in 1859.

Shutterstock

Today, when the poet’s birthday is marked on January 25 around the world, many different and contradictory versions of Burns will be remembered. In their complex responses to Dumfries, where the poet’s death has often seemed more tangible than his birth, early literary tourists like the Wordsworths and Keats show that this is nothing new.

After all, the role of a national poet – a vehicle for our thoughts and dreams – underlines how much of both memory and geography is the work of the imagination.

Gerard Lee McKeever, British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

22.1.20

Kelty Community Cinema unveils arts hub vision to build on funding boost

The group behind Kelty Community Cinema has aspirations of transforming a former local hub into an arts centre. Led by postie and movie buff Wayne ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

21.1.20

What meat eaters really think about veganism – new research

Shutterstock/Polina Yanchuk

Most people in the UK are committed meat eaters – but for how long? My new research into the views of meat eaters found that most respondents viewed veganism as ethical in principle and good for the environment.

It seems that practical matters of taste, price, and convenience are the main barriers preventing more people from adopting veganism – not disagreement with the fundamental idea. This could have major implications for the future of the food industry as meat alternatives become tastier, cheaper and more widely available.

My survey of 1,000 UK adult men and women found that 73% of those surveyed considered veganism to be ethical, while 70% said it was good for the environment. But 61% said adopting a vegan diet was not enjoyable, 77% said it was inconvenient, and 83% said it was not easy.

Other possible barriers such as health concerns and social stigma seemed not to be as important, with 60% considering veganism to be socially acceptable, and over half saying it was healthy.

The idea that most meat eaters agree with the principles of veganism might seem surprising to some. But other research has led to similar conclusions. One study for example, found that almost half of Americans supported a ban on slaughterhouses.

The prevalence of taste, price, and convenience as barriers to change also mirrors previous findings. One British survey found that the most common reason by far people gave for not being vegetarian is simply: “I like the taste of meat too much.” The second and third most common reasons related to the high cost of meat substitutes and struggling for meal ideas.

These findings present climate and animal advocates with an interesting challenge. People are largely aware that there are good reasons to cut down their animal product consumption, but they are mostly not willing to bear the personal cost of doing so.

Food motivation

Decades of food behaviour research has shown us that price, taste and convenience are the three major factors driving food choices. For most people, ethics and environmental impact simply do not enter into it.

Experimental research has also shown that the act of eating meat can alter peoples’ views of the morality of eating animals. One study asked participants to rate their moral concern for cows. Before answering, participants were given either nuts or beef jerky to snack on.

The researchers found that eating beef jerky actually caused participants to care less about cows. People seem not to be choosing to eat meat because they think there are good reasons to do so – they are choosing to think there are good reasons because they eat meat.

In this way, the default widespread (and, let’s be honest, enjoyable) behaviour of meat eating can be a barrier to clear reasoning about our food systems. How can we be expected to discuss this honestly when we have such a strong interest in reaching the conclusion that eating meat is okay?

Fortunately, things are changing. The range, quality, and affordability of vegan options has exploded. My survey was conducted in September 2018, a few months before the tremendously successful release of Greggs’ vegan sausage roll.

Since then, we have seen an avalanche of high-quality affordable vegan options released in the British supermarkets, restaurants and even fast food outlets. These allow meat eaters to easily replace animal products one meal at a time. When Subway offers a version of its meatball marinara that is compatible with your views on ethics and the environment, why would you choose the one made from an animal if the alternative tastes the same?

The widespread availability of these options means that the growing number of vegans, vegetarians and flexitarians in the UK have more choice than ever. Not only will this entice more people to try vegan options, but it will make it far easier for aspiring vegetarians and vegans to stick to their diets.

With consumer choice comes producer competition, and here we will see the magic of the market. If you think those looking to cut down their meat consumption are spoilt for choice in 2020, just wait to see the effect of these food giants racing to make their vegan offerings better and cheaper as they compete for a rapidly growing customer segment.

We may be about to witness an explosion in research to perfect plant-based meat analogues. Meanwhile, the development of real animal meat grown from stem cells without the animals is gaining pace.

Cheaper and tastier

While these replacements get tastier, more nutritious and cheaper over the next ten years, meat from animals will largely stay the same. It is no wonder the animal farming industry is nervous. Demand for meat and dairy is falling drastically while the market for alternatives has skyrocketed.

In the US, two major dairy producers have filed for bankruptcy in recent months, while a recent report estimated that the meat and dairy industries will collapse in the next decade.

This leaves the average meat eater with a dilemma. Most agree with the reasons for being vegan but object to the price, taste, and convenience of the alternatives.

As these alternatives get cheaper, better and more widespread, meat eaters will have to ask themselves just how good the alternatives need to be before they decide to consume in line with their values. Being one of the last people to pay for needless animal slaughter because the alternative was only “pretty good” will not be a good look in the near future.

Chris Bryant, PhD Candidate, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

20.1.20

19.1.20

Our Aberdeen: What London flower girl could be so pretty?

The acclaimed society portrait artist Sir Oswald Birley usually painted ... in the “Nameless Exhibition” of contemporary British artists at London's Grosvenor ... the artist's name attached) and reproduced in The Illustrated London News, ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

17.1.20

Why you don't see many black and ethnic minority faces in cultural spaces

Why you don't see many black and ethnic minority faces in cultural spaces – and what happens if you call out the system

You’re great, just don’t get too big for your boots.

Have you ever been to the theatre, looked around, and thought about how predominantly white the audience is? Does the same impression come to mind when visiting museums? If it does and the answer is a resounding yes, then you’re not alone. There is a major problem in Britain’s cultural industry and it’s time we all took a hard look at why.

For years now, there has been a growing recognition of the ethnic inequalities in the creative sector. Arts Council England found it to be prevalent and persistent, particularly in theatres and museums: 12% of the workforce in national organisations in the council’s portfolio were from black and minority ethnic backgrounds, and just 5% across its major partner museums. In positions of leadership, this fell to only 9% of chief executives and 10% of artistic directors in national portfolio organisations. On executive boards at partner museums it was 3%. A recent survey showed that 92% of top British theatre leaders were white.

In TV, a report from communications regulator Ofcom showed that ethnic minorities were also considerably underrepresented. It highlighted “a cultural disconnect between the people who make programmes and the millions who watch them”.

This is all despite a number of leading institutions introducing action plans and policies to improve their diversity. While Arts Council England launched the Creative Case for Diversity in 2011, to emphasise the importance and value of diversity in the arts and its significance in enriching artistic practice, leadership and audiences, leading broadcasters the BBC and Channel 4 have ramped up efforts to increase diversity. Yet change of the status quo seems to be minimal and in some cases static. The cultural sector remains steeped in ethnic inequality.

Failing strategies

There are many factors for why Britain’s cultural sector appears to be circumscribed by whiteness in ideology and practice, production and consumption. Diversity strategies seem to be failing so far, partly because “diversity” itself is a problematic term that can often dilute the problem and depoliticise the issue of racial discrimination. In the creative sector, it has morphed from an aspiration to tackle racial inequality into a drive for better business and economics – a rationale that downshifts the social impact of ethnic inequality, as film studies fellow Clive Nwonka argues.

The business case for diversity can help campaign for ethnic equality, but using it merely as a business tool can mask discriminatory practices and shift focus away from deeper issues of structural racism – for example, in embedded attitudes about art production, its consumers and its exclusivity; attitudes that enforce creative hierarchies that align with racial and class hierarchies.

Myths about high art and its audience

Many a myth still exist about cultural creation, what constitutes high or low culture, and the attitudes of ethnic minorities towards cultural participation. Commonly held opinions include, for example, that audiences from black and ethnic minorities are hard to engage – a view that ignores the lack of ethnic representation in the sector, among other realities pertaining to education and class.

Meera Syal.

In 2014, and in response to calls by actress Meera Syal for theatres to cater to Asian audiences, distinguished actor Janet Suzman was staunchly criticised for claiming that theatre was a “white invention”, that “runs in their [white people’s] DNA”. Consciously or not, statements like these contribute to a segregation of culture, and a hierarchy of cultural production.

In What is this “black” in black popular culture?, Stuart Hall articulated how the ordering of culture into high and low serves to establish cultural hegemony:

It is an ordering of culture that opens up culture to the play of power, not an inventory of what is high versus what is low at any particular moment.

Take grime

Ethnic and racial hierarchies get reproduced through cultural hierarchies. For example, grime music is tolerated, even celebrated, as long as it remains an ethnic genre, confined to a black experience, and so subject to hierarchical cultural positioning.

The outrage that a number of public figures (such as presenter Piers Morgan and academic Paul Stott) showed towards Stormzy when he recently affirmed that racism exists in the UK, appeared to stem from their sense that the grime artist has succeeded courtesy to whiteness, its tolerance and patronage, as a tweet from Stott suggested:

It all starts with education

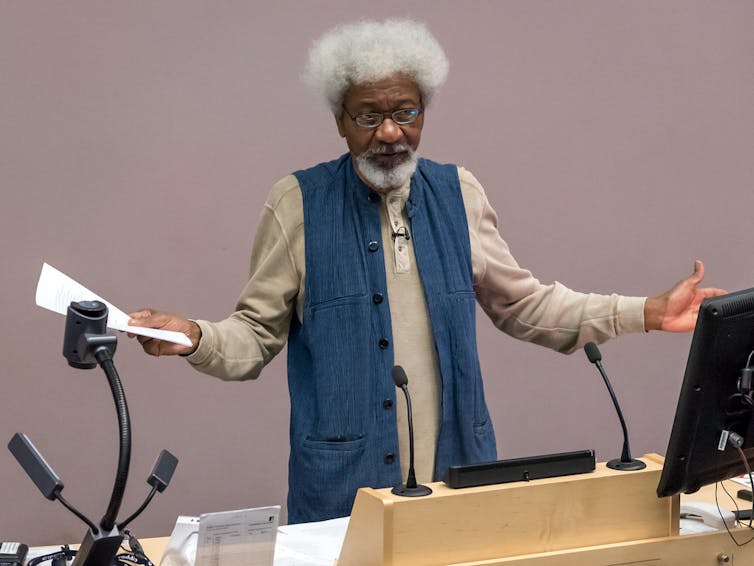

Attitudes about culture are also produced and reproduced through education. Theatre departments are probably one of the first and most essential blocs in the chain of supply for the theatre sector and cultural industry in general. Yet a predominantly white curriculum continues to be the norm in arts and theatre subjects – that is because for the most part, the canon has been constructed in the image of whiteness. As a consequence, most theatre students will study the works of Shakespeare and Bertolt Brecht, for example, but not many will consult the plays of Nigerian Nobel Laureate writer Wole Soyinka, or Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous.

Wole Soyinka: we don’t know either.

Black and ethnic minorities are underrepresented as students, academics and authors on reading lists. As one notable report put it: although a welcoming environment, the discipline remains monocultural in terms of both its staff and curricula.

The few taught modules that focus on non-white theatres texts are offered as part of an optional stream, to add “flavour” rather as part of the core canon. This reproduces the hierarchy of knowledge with whiteness on top, and ethnic contributions valued through their proximity to whiteness. It also exoticises and exceptionalises non-white modules, created to appeal to non-white students. While these texts, and those who consume them, are both kept part of and inside the institution, they remain outside its frame of cultural influence and power.

Read more:

Some scholars and activists are taking bold actions to decolonise the discipline from within. Campaigns such as Why is my curriculum so white challenge the lack of diversity in UK universities and the dominance of white eurocentric teaching materials.

Yet attitudes towards cultural production remain set within a frame of mind that centres whiteness as the custodian of high art. When the principal of the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama was asked about quotas as a potential way to boost diversity in 2018, his concern for the school’s standards and reputation implied that black and ethnic minorities might not possess the finesse required to meet such “standards”.

Others, such as the Black British Classical Foundation, aim to nurture interest and participation in art forms often seen as exclusionary.

It plays out in institutions

Our representations are created in cultural institutions, and it is within their daily operation, structures and processes that ethnic inequalities are either perpetuated or mitigated.

For the last two years, my colleagues and I have been researching how institutions reproduce or mitigate ethnic inequalities in cultural production. Throughout our research and interviews, the idea of exclusivity has been reiterated again and again by both majority (white) ethnic and minority ethnic staff.

Although some institutions have introduced diversity initiatives, progress seems slow and tied up to arts funding structures that are temporary and one directional – ultimately serving the institutions rather than the ethnic minorities they seek to engage. Organisations may gain funding by appealing to funders’ diversity agendas, but their engagement with ethnic minority communities and artists is rarely sustainable or lasting, leaving creatives feeling exploited and perhaps further marginalised.

Bafta: still struggling.

Many theatres and TV production companies also aim to increase representations on stage and screen, but that really only serves as window dressing. Ultimately, creators, writers, producers, senior management and commissioners remain mostly white. The stories they tell are therefore also mostly white. The lack of diversity in the 2020 Bafta nominations is an example of a film culture that struggles to produce, represent or celebrate ethnic minorities.

Of course, class plays a major factor in perpetuating ethnic inequalities in the cultural sector, but it is also sometimes used to camouflage structural racism in its institutions. Race and class can work in tandem to marginalise ethnic minorities in cultural spaces, but racism in cultural spaces has a direct link to racism in social spaces and that has impact on how the nation imagines itself – dictating who belongs and who doesn’t.

There is a silver lining, though. New modes of cultural production and consumption via avenues like Netflix, YouTube, and Instagram are changing traditional cultural production practices. Netflix’s large investment in original content and its subscription model means that the network is commissioning diverse content to cater for and further attract a receptive diverse audience. Such trends may yet force institutions to properly address their lack of diversity.

A cultural sector that is able to represent Britain’s diverse communities and respond to new digital means of production and distribution cannot happen without a diverse workforce, institutions that conceptualise diversity as a core strength, and funding bodies that facilitate long-term ethnic equality in the sector rather than short-lived diversity initiatives.

Roaa Ali, Research Associate (Cultural Production and Consumption), University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

16.1.20

Cecily Brown will fill grand birthplace of Winston Churchill with images of broken Britain

UK artist says exhibition at Blenheim Palace is a timely opportunity to ... The UK artist Cecily Brown will ponder on the issue of broken Britain and the ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

14.1.20

13.1.20

How 'WhatsApp group admin' became one of the most powerful jobs in politics

When the British parliament asked the government in 2019 to publish the messages that key officials were sending to each other about Brexit via text message, email, Facebook and messaging apps, it drew attention to the extent to which elected officials have been sidestepping official channels in their communications.

The push came in September, when tensions over Brexit were high and there were concerns that the government was being dishonest about its motives for suspending parliament for five weeks – a move that was ultimately ruled as unlawful by the Supreme Court.

Clearly parliamentarians thought important information was being shared on these platforms that the public needed to know about. In a rather telling move, the government refused to comply with the request. The incident shows how messaging apps have come to play an important role in operations – and how they allow officials and politicians to evade scrutiny.

Political groups are increasingly alert to the potential of messaging services like WhatsApp and Telegram for operating closed communities. The emergence of the European Research Group (ERG) within the UK Conservative Party is a case in point. This is an organisation for Conservative members of parliament who were enthusiastic about leaving the European Union long before the 2016 referendum and subsequently pushed for as hard a Brexit as possible.

Shortly after the referendum, key ERG leaders came together in a WhatsApp chat group. The then chairman of what was still a little-known organisation, Steve Baker, became an administrator of the group.

By the time the existence of the WhatsApp group was revealed four months later, the ERG was becoming more and more influential within the Conservative Party. Some would argue that its actions ultimately helped to thwart Theresa May’s attempts to get her Brexit deal through parliament. The ERG voted again and again to block her deal, denying her the votes she needed.

This was quite an achievement for an organisation largely made up of backbenchers. At times, it isn’t even entirely clear to the general public which parliamentarians are members of the ERG, yet they were able to exert significant influence over their party without having to go public with their operations.

That was, in no small, part, thanks to networks beyond the reach of traditional scrutiny mechanisms such as the WhatsApp group. The ERG WhatsApp group members described their chat as an “extremely effective” way of organising as it helped them to agree on “lines to take” in parliament and in the media.

Many similar WhatsApp groups now exist in parliament. They unite MPs of different parties that range from Labour factions to the “One Nation” group of moderate Tories. Communicating in a WhatsApp group even allows MPs to organise across party boundaries, helping them to defy the official party line on key issues.

This new type of political organising affects how power is distributed within parties and movements. A traditional party has a leader and a whip; a WhatsApp group has an administrator. A new breed of operative therefore wields significant power.

Administrators make decisions regarding who to add or remove from a chat and, often, what content is shared. This means that, if a group gets big enough, a relatively low-level party operative can become an important figure. In the traditional sense of party structures, Steve Baker, for example, is not a leading politician. But as administrator of the ERG WhatsApp group, he can control who is in and who is out of a discussion group that has played a central role in the direction taken on Brexit.

Research in recent social movements such as Occupy Wall Street and the Indignados has shown that social media administrators can become leading voices in protest communities even when such movements are presented as “leaderless” and “horizontal”. However, social movements are not the same as elected representatives. They do not have to conform to the same regulations around transparency and accountability that apply to our elected politicians.

The content of influential online groups is also often as invisible as the people taking part in them. This is because messaging platforms like WhatsApp are encrypted and designed as extremely private spaces.

There can be benefits to encryption of course. Protest movements depend on this security to protect themselves from the threat posed by undemocratic states. But elected politicians should not abuse the capabilities of digital media like the encryption mechanisms of platforms. Otherwise, society risks losing track of government communications related to important matters such as Brexit. The history can be deleted or hidden away in private company servers. While Downing Street’s confidential memos on the prorogation were eventually released, such digital communications remain out of reach.

The other problem here is that government business is increasingly conducted on the communication platforms of private companies. What power does this give Whatsapp, and its parent company Facebook, over the communications of our governments?

We still know relatively little about how messaging platforms are reshaping parties’ internal operations. Unless we turn the spotlight on these internal dynamics, shadow organisations inside parties will continue to influence politics with no accountability.

Aliaksandr Herasimenka, University of Westminster and Anastasia Kavada, University of Westminster

Aliaksandr Herasimenka, PhD candidate, Visiting Lecturer, School of Media & Communication, University of Westminster and Anastasia Kavada, Senior Lecturer, School of Media and Communication, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The push came in September, when tensions over Brexit were high and there were concerns that the government was being dishonest about its motives for suspending parliament for five weeks – a move that was ultimately ruled as unlawful by the Supreme Court.

Clearly parliamentarians thought important information was being shared on these platforms that the public needed to know about. In a rather telling move, the government refused to comply with the request. The incident shows how messaging apps have come to play an important role in operations – and how they allow officials and politicians to evade scrutiny.

Political groups are increasingly alert to the potential of messaging services like WhatsApp and Telegram for operating closed communities. The emergence of the European Research Group (ERG) within the UK Conservative Party is a case in point. This is an organisation for Conservative members of parliament who were enthusiastic about leaving the European Union long before the 2016 referendum and subsequently pushed for as hard a Brexit as possible.

Shortly after the referendum, key ERG leaders came together in a WhatsApp chat group. The then chairman of what was still a little-known organisation, Steve Baker, became an administrator of the group.

By the time the existence of the WhatsApp group was revealed four months later, the ERG was becoming more and more influential within the Conservative Party. Some would argue that its actions ultimately helped to thwart Theresa May’s attempts to get her Brexit deal through parliament. The ERG voted again and again to block her deal, denying her the votes she needed.

This was quite an achievement for an organisation largely made up of backbenchers. At times, it isn’t even entirely clear to the general public which parliamentarians are members of the ERG, yet they were able to exert significant influence over their party without having to go public with their operations.

That was, in no small, part, thanks to networks beyond the reach of traditional scrutiny mechanisms such as the WhatsApp group. The ERG WhatsApp group members described their chat as an “extremely effective” way of organising as it helped them to agree on “lines to take” in parliament and in the media.

Many similar WhatsApp groups now exist in parliament. They unite MPs of different parties that range from Labour factions to the “One Nation” group of moderate Tories. Communicating in a WhatsApp group even allows MPs to organise across party boundaries, helping them to defy the official party line on key issues.

The all-seeing admin

This new type of political organising affects how power is distributed within parties and movements. A traditional party has a leader and a whip; a WhatsApp group has an administrator. A new breed of operative therefore wields significant power.

Administrators make decisions regarding who to add or remove from a chat and, often, what content is shared. This means that, if a group gets big enough, a relatively low-level party operative can become an important figure. In the traditional sense of party structures, Steve Baker, for example, is not a leading politician. But as administrator of the ERG WhatsApp group, he can control who is in and who is out of a discussion group that has played a central role in the direction taken on Brexit.

Research in recent social movements such as Occupy Wall Street and the Indignados has shown that social media administrators can become leading voices in protest communities even when such movements are presented as “leaderless” and “horizontal”. However, social movements are not the same as elected representatives. They do not have to conform to the same regulations around transparency and accountability that apply to our elected politicians.

An encrypted universe

The content of influential online groups is also often as invisible as the people taking part in them. This is because messaging platforms like WhatsApp are encrypted and designed as extremely private spaces.

There can be benefits to encryption of course. Protest movements depend on this security to protect themselves from the threat posed by undemocratic states. But elected politicians should not abuse the capabilities of digital media like the encryption mechanisms of platforms. Otherwise, society risks losing track of government communications related to important matters such as Brexit. The history can be deleted or hidden away in private company servers. While Downing Street’s confidential memos on the prorogation were eventually released, such digital communications remain out of reach.

The other problem here is that government business is increasingly conducted on the communication platforms of private companies. What power does this give Whatsapp, and its parent company Facebook, over the communications of our governments?

We still know relatively little about how messaging platforms are reshaping parties’ internal operations. Unless we turn the spotlight on these internal dynamics, shadow organisations inside parties will continue to influence politics with no accountability.

Aliaksandr Herasimenka, University of Westminster and Anastasia Kavada, University of Westminster

Steve Baker decides who talks Brexit. PA

Aliaksandr Herasimenka, PhD candidate, Visiting Lecturer, School of Media & Communication, University of Westminster and Anastasia Kavada, Senior Lecturer, School of Media and Communication, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

£50000 raised by art cafe since 2015

AN artist has raised more than £50,000 for good causes in four years. ... the Alzheimer's Society, British Heart Foundation and Royal British Legion.

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

10.1.20

What's On: Light Festival, Battersea Power Station

On display in Circus West Village, the installations will be making their UK ... “The Light Festival will strengthen the art and culture offering already ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

7.1.20

Patrick Staff: On Venus | Serpentine Exhibition

For their newly commissioned exhibition at the Serpentine, Patrick Staff presents their most ambitious work to date: On Venus is a site-specific installation exploring structural violence, registers of harm and the corrosive effects of acid, blood and hormones through architectural intervention, video and print.

Former art teacher who battled mental health struggles transforms Dalton Leisure Centre

Former art teacher who battled mental health struggles transforms Dalton Leisure Centre. By Eleanor Ovens @NWEMLive Reporter. See all 6 photos ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

4.1.20

Nuart: Aberdeen street art festival created 'phenomenal legacy'

An Aberdeen street art festival has left a “phenomenal legacy” that is free for anyone to access, use and enjoy, a lead organiser has claimed. Business ...

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

2.1.20

Taking back control

We can take back control by building a popular network, a movement built from the ground up. Now is not the time to give up hope. A people's network can help establish true democracy and put real power in the hands of the people.

In this article on openDemocracy entitled The revolution will be networked Paul Hilder offers some very good arguments as to how the left needs to organise going forward. It says:

In this article on openDemocracy entitled The revolution will be networked Paul Hilder offers some very good arguments as to how the left needs to organise going forward. It says:

A networked labour movement will help the Labour party to forge better alliances with the growing plurality of progressive and left forces. It requires moving decisively to harness technology in the service of individuals, communities and the common good, to fundamentally and irreversibly shift power into the hands of the many.I urge you to read it.

1.1.20

Calling all artists! Open exhibition launched that could net you £2000

A search for new or undiscovered art talent in Retford has begun after The Harley ... about how to enter the competition visit www.harleygallery.co.uk.

* The full article is published here...

* The full article is published here...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Kids React to Art - Cildo Meireles's Babel | Tate #kidsreact #funnyvideo

📻 We asked kids to react to Cildo Meireles's Babel, one of 25 artworks celebrating Tate Modern's 25th birthday, and this is what th...