For many it was the adventure of a lifetime, for others it was unbearable heartache to leave loved ones behind. For a young Robert Burns in 1786, it was a way out from penury, failure and disgrace. Only the unexpected success of his first published collection, Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, prevented his departure to Jamaica to work as slave master on a sugar plantation. Literary fame ensued and Burns remained in the land of his birth.

Since 1800, 4 million Scots have left their country in search of a better life, bound for destinations all over the world. For two decades I have been asking questions of Scottish emgirants on five continents to understand the huge adjustments needed of starting a new life overseas.

Why did so many Scots leave their homeland? Who were they? Where did they come from and where did they go? What were the pleasures and pains of crossing to new worlds? How did they make their mark and imprint their identity on the places where they put down new roots? And what have been the experiences and sentiments of those who have returned to Scotland, either permanently, or as visitors?

My interviews with 100 of these Scots have now been published in the form of an audiobook, Testimonies of Transition, focusing on the story of this diaspora. This tale has been well told in print but rarely heard in the words of those who left Scotland, many never to return.

Spirit of adventure

In the recordings I’ve made, we can hear immediately, for example, whether emigrants have retained or lost their accents and dialects. From the rhythm and tone of people’s voices, we can discern the adventurous spirit and occasionally the anguish of those who took this momentous step, as they recall the difficult decisions they had to make and the challenges they faced.

My interviewees included some who left during the significant exoduses that followed the two world wars. Among them was Morag Bennett, who at the age of ten left Benbecula in the Western Isles, for Alberta in Canada on board the SS Marloch in April 1923.

Stories like Morag’s tell us much about life in Scotland during the 1920s. She left in a year when more than 89,000 Scots sought new lives overseas. Their decisions were prompted by the socio-economic crisis in the aftermath of war, unemployment, and – in the Western Isles – the renewed spectre of famine as a result of poor harvests and the loss of fishing markets, coupled with the lack of promised land reforms. At the same time, recruitment agents, family and friends already overseas and unprecedented financial assistance from the British government persuaded many that a better future lay elsewhere.

Morag’s overriding emotion was excitement. She remembered the “huge icebergs” that she saw during the two-week Atlantic crossing and the novelty of indoor plumbing on board ship. “We never had running water in Benbecula,” she recalled. “We didn’t know what the bowl and the taps and all these sort of things were.” Life on the prairie was equally exciting, but eight decades on, she admitted that her parents had been daunted and depressed by the harsh extremes of the climate.

Agnes MacGilvray, born in Whithorn in 1908, was another interviewee whose testimony was infused with recollections of a great adventure. In conversation three weeks before her 101st birthday, Agnes described how in 1930 she had been persuaded to go to New York by a friend whose cousins had painted a glowing picture of better wages and working conditions across the Atlantic.

She spent nine years as a live-in maid, regularly changing jobs in a way that concerned her brother in Scotland. She recalled that, after updating him with a new address, he responded acerbically: “What are you playing at? This is the fourth address you’ve had in two years.” But for Agnes work was the key that unlocked opportunities for having fun, seeing as many Broadway shows as she could afford. “I went to more musicals and more theatre and more everything,” she remembered with infectious glee.

Learning new skills

The choice of destination could be accidental. In 1951 Angus Pelham Burn, fresh from his agriculture studies in Aberdeen, responded to a press advertisement urging readers to “join the romantic fur trade” in northern Ontario.

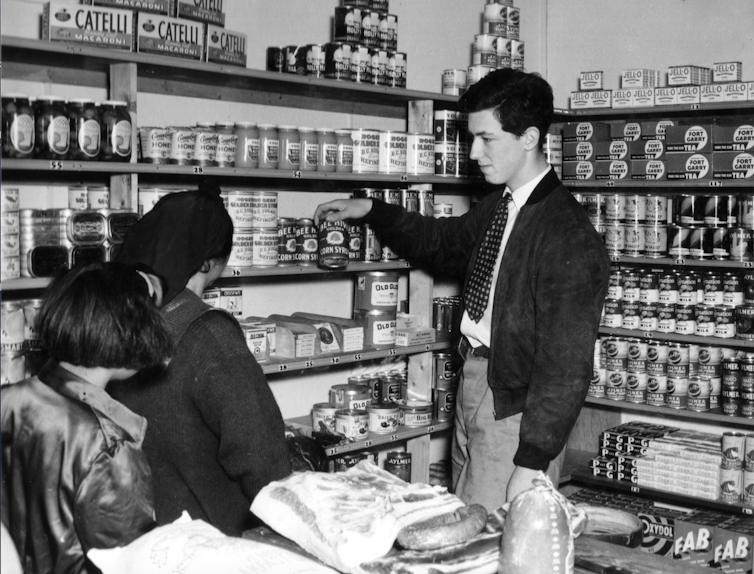

Angus spent the next seven years working for the Hudson’s Bay Company, where, as well as managing a store, he acquired skills in driving a dog team, flying a plane and pulling teeth. “I learned all sorts of things that you’d never do nowadays,” he recalled, attributing his later success in business and farming in Scotland to his character-building sojourn in the frozen Canadian north.

The vast majority of interviewees had no regrets about emigrating. Those who left as children adjusted most readily, since they had fewer memories of Scotland and wanted to fit in. Adults varied in the strength of their attachment to their homeland. Some sought out fellow Scots, patronised Scottish clubs and made regular visits home. Others preferred to concentrate on building new lives and careers, making a deliberate decision to assimilate and took out citizenship in the countries where they settled.

About a third returned permanently to Scotland. A few came back because of crushing homesickness, but for most, the decision was not a result of disappointment or failure. They returned to pursue careers, shoulder family responsibilities, or retire. Just as the emigrants took Scottish culture to the diaspora, those who returned brought new ideas and skills acquired overseas to enrich their country.![]()

Marjory Harper, Professor of History, University of Aberdeen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.