Cats in the middle ages: what medieval manuscripts teach us about our ancestors’ pets

Cats had a bad reputation in the middle ages. Their presumed links with paganism and witchcraft meant they were often treated with suspicion. But despite their association with the supernatural, medieval manuscripts showcase surprisingly playful images of our furry friends.

From these (often very funny) portrayals, we can learn a lot about medieval attitudes towards cats – not least that they were a central fixture of daily medieval life.

In the middle ages, men and women were often identified by the animals they kept. Pet monkeys, for example, were considered exotic and a sign that the owner was wealthy, because they had been imported from distant lands. Pets became part of the personal identity of the nobility. Keeping an animal that was lavished with attention, affection and high-quality food in return for no functional purpose – other than companionship – signified high status.

It was not unusual for high-status men and women in the middle ages to have their portrait completed in the company of a pet, most commonly cats and dogs, to signify their elevated status.

It is commonplace to see images of cats in iconography of feasts and other domestic spaces, which appears to reflect their status as a pet in the medieval household.

In Pietro Lorenzetti’s Last Supper (above), a cat sits by the fire while a small dog licks a plate of leftovers on the ground. The cat and dog play no narrative role in the scene, but instead signal to the viewer that this is a domestic space.

Similarly, in the miniature of a Dutch Book of Hours (a common type of prayer book in the middle ages that marked the divisions of the day with specific prayers), a man and woman feature in a cosy household scene while a well looked-after cat gazes on from the bottom left-hand corner. Again, the cat is not the centre of the image nor the focus of the composition, but it is accepted in this medieval domestic space.

Just like today, medieval families gave their cats names. A 13th-century cat in Beaulieu Abbey, for example, was called “Mite” according to the green ink lettering that appears above a doodle of said cat in the margins of a medieval manuscript.

Royal treatment

Cats were well cared for in the medieval household. In the early 13th century, there is mention in the accounts for the manor at Cuxham (Oxfordshire) of cheese being bought for a cat, which suggests that they were not left to fend for themselves.

In fact, the 14th-century queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria, spent excessive amounts of money on accessories for her pets. In 1387, she commissioned a collar embroidered with pearls and fastened by a gold buckle for her pet squirrel. In 1406, bright green cloth was bought to make a special cover for her cat.

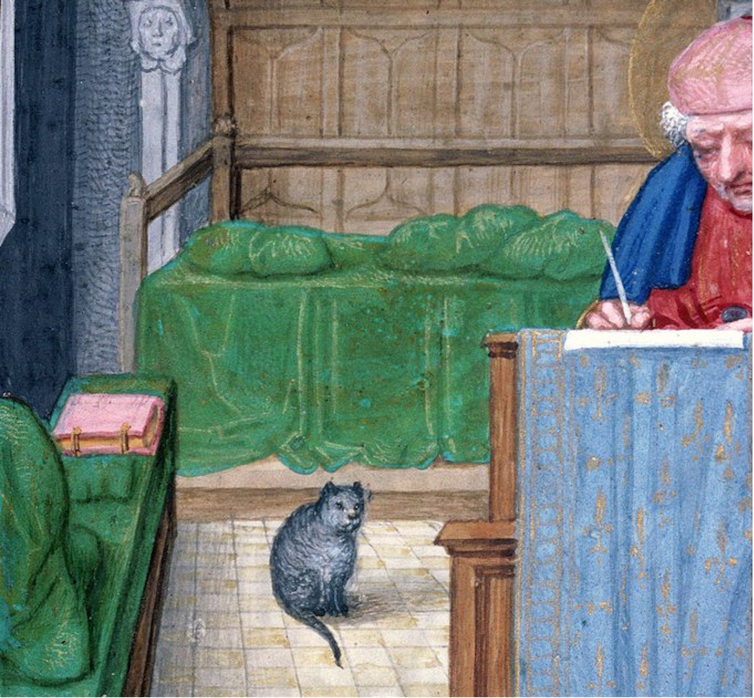

Cats were also common companions for scholars, and eulogies about cats were not uncommon in the 16th century. In one poem, a cat is described as a scholar’s light and dearest companion. Eulogies such as this suggest a strong emotional attachment to pet cats, and show how cats not only cheered up their masters but provided welcome distractions from the hard mental craft of reading and writing.

Cats in the cloisters

Cats are found in abundance as a status symbol in medieval religious spaces. There are lots of medieval manuscripts that feature, for example, illuminations (small images) of nuns with cats, and cats frequently appear as doodles in the margins of Books of Hours.

But there is also much criticism about the keeping of cats in medieval sermon literature. The 14th-century English preacher John Bromyard considered them useless and overfed accessories of the rich that benefited while the poor went hungry.

Cats are also recorded as being associated with the devil. Their stealth and cunning when hunting for mice was admired – but this did not always translate into qualities desirable for companionship. These associations led to the killing of some cats, which had detrimental effects during the Black Death and other middle age plagues, when more cats may have reduced flea-infested rat populations.

Because of these associations, many thought that cats had no place in the sacred spaces of religious orders. There do not seem to have been any formal rules, however, stating that members of religious communities were not allowed to keep cats – and the constant criticism of the practice perhaps suggests that pet cats were common.

Even if they were not always considered as socially acceptable in religious communities, cats were still clearly well looked after. This is evident in the playful images we see of them in monasteries.

For the most part, cats were quite at home in the medieval household. And as their playful depiction in many medieval manuscripts and artwork makes clear, our medieval ancestors’ relationships with these animals were not too different from our own.![]()

Madeleine S. Killacky, PhD Candidate, Medieval Literature, Bangor University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.