[Re]Engtanglements, Author provided

It’s an extraordinary collection of portraits from Nigeria and Sierra Leone taken between 1909 and 1915, when Britain was at the height of its empire. The archive shows a vast array of faces – of women, children and men – some distant, some suspicious, some proud, some confused, some joyous. Most are photographed against a canvas backdrop, some with number boards above their heads, all of them silent.

Many of our museums and archives are filled with such traces of Britain’s colonial past, and exist as troubling presences in our public institutions. Many of these collections illustrate the way academic subjects such as anthropology, geography, linguistics and botany are entangled with Britain’s colonial history.

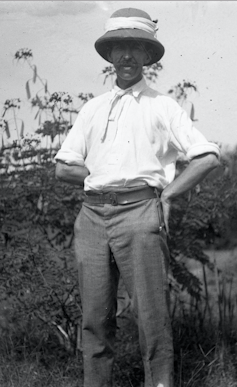

British anthropologist Northcote Thomas.

Royal Anthropological Institute, Author provided

For decades, much of this material has remained hidden, its access largely restricted to academic researchers. There has been a reluctance to confront these relics of outmoded and objectionable ideologies. Now, amid renewed calls to “decolonise” our cultural institutions, there is a desire to open up the colonial archive to new forms of scrutiny.

I have been leading a collaborative project called [Re:]Entanglements, which exemplifies this new spirit of openness through art, film and community engagement.

The project explores this remarkable photographic archive of people’s faces, as well as recordings, artefacts, botanical specimens and fieldnotes – the legacy of a series of anthropological surveys funded by the colonial governments of Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone in the first two decades of the 20th century. These surveys were led by Northcote Thomas (1868-1936), the first government anthropologist to be appointed by Britain’s Colonial Office.

Reframing the past: art, outreach and fieldwork

On the one hand, [Re:]Entanglements seeks to better understand the historical relationship between anthropology and colonialism in the early 20th century. On the other, crucially, it is exploring the significance of these archives for different communities in West Africa and the UK today.

The research team has retraced Thomas’s survey itineraries in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, bringing back copies of photographs and sound recordings to the descendants of those surveyed over a century ago. It has been a privilege to witness people listening to the voices of their ancestors and seeing the faces of their great-grandparents, often for the first time.

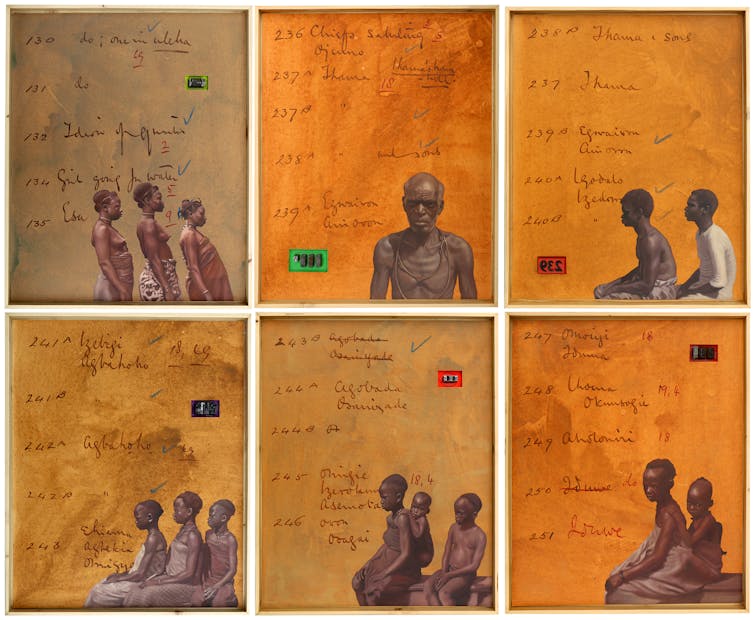

Nigerian artist Kelani Abass’s mixed media work that uses Northcote Thomas’s survey material.

Kelani Abass, Author provided

The project has also established collaborations with contemporary artists in West Africa, inviting them to respond to the archive and illuminate its underlying politics through their work. The Igbo artist, Chukwunonso Uzoagba, for example, has restaged one of Thomas’s photographs of a traditional wrestling festival as a contest between an indigenous wrestler and Thomas himself, representing the struggle between colonised and coloniser.

Another artist, Kelani Abass, has produced a series of 17 mixed-media works called Colonial Indexicality based on the albums of Thomas’s photographs that we discovered in the National Museum in Lagos. These are the only surviving records of Thomas’s surveys in Nigeria.

Abass’s work captures the fading textures of the archive and the bureaucracy involved in documentation, and stands as a visually arresting comment on the fragility of memory. It also lays bare the paradox of colonialism as a force that both destroyed traditional ways of life and preserved them.

The view from London

Other forms of public engagement with this project have been taking place in the UK as well. A young people’s initiative at the South London Gallery, for example, includes an exploration of Peckham’s many connections with Nigeria and Sierra Leone across the generations.

Another initiative resulted in the film I made with Chris Allen of production company The Light Surgeons. Called Faces|Voices, the film has just won the best research film prize for 2019 at the Research in Film Awards (RIFA).

Although researchers have written a great deal about the politics of representation of African people, in Faces|Voices we wanted to explore a wider range of responses to Northcote Thomas’s photographs – particularly among British people with an African heritage.

A British woman looks at an image of a Nigerian woman from a 1911 colonial survey in the film Faces|Voices.

[Re]Entanglements, Author provided

We invited a number of people from across London – some with direct links to the places in which Thomas worked, and some engaged in community education, activism or the reparations debate – to confront some of the more problematic images produced by the English anthropologist. These colonial-era portraits sought to document the physical characteristics of people belonging to different ethnic groups.

For many, these epitomise the violence of colonial science, treating individuals as specimens to be collected, sorted and categorised into racial or tribal types. They make up about half of around 7,500 photographs that Northcote Thomas took in West Africa.

Woman and child photographed in Southern Nigeria in 1911.

NW Thomas, Author provided

Since the many West African faces photographed for Thomas’s archive have no voice, we can only guess what the experience of being photographed by this pith-helmeted anthropologist may have been like. Was it violent or humiliating? Was it an amusing distraction from everyday chores? Was it empowering? What can we read in the mute expressions of those photographed?

In Faces|Voices, we find that the same photograph seen through different eyes can elicit quite different responses. Where one person sees coercion, another detects merely boredom. The crushing experience of colonial oppression is discerned in one subject’s expression. Optimism and resilience is read in another’s.

It is clear, then, that the “meaning” of these photographs has as much to do with what the viewer brings to the image as what the image presents. Perhaps most surprising is the sympathetic view of the face of Northcote Thomas himself. While for one viewer the image of Thomas exemplifies the “stiff upper lip” of a British colonial, others remark on what they see as kindness, integrity and humanity.

Young woman photographed by Northcote Thomas in Southern Nigeria in 1911.

NW Thomas, Author provided

As the legacy of a colonial project, the capacity of these photographs to unsettle us is beyond question. But our film Faces|Voices also complicates any simple reading of these images beyond the idea of “colonised” and “coloniser”. There is laughter too in the colonial archive, and the voices of the black British people in the film articulate a need for us to re-humanise the subjects of Thomas’s photographic portraits.

While it is crucial that we confront the difficult histories embodied in such archives, it is important that we do so attentively, mindful of their complexities and contradictions.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.