The announcement by Boris Johnson, the UK prime minister, that pubs in England will be allowed to resume trading from July 4 was greeted with rousing cheers from some. But having a pint in the pandemic era will be slightly different. While two-metre social distancing rules are being relaxed to one metre to ensure economic viability for publicans, to maintain the safety of customers and staff, pubs will where practical be restricted to “table service”.

Standing at the bar is one of the most cherished rituals of the British pub experience – and many people are worried that the new rules could be the beginning of the end of a tradition that dates back centuries. Except, it doesn’t – the bar as we now know it is of relatively recent vintage and, in many respects, the new regulations are returning us to the practices of a much earlier era.

Before the 19th century, propping up the bar would have been an unfamiliar concept in England’s dense network of alehouses, taverns and inns. Alehouses and taverns in particular were seldom purpose-built, but were instead ordinary dwelling houses made over for commercial hospitality. Only their pictorial signboards and a few items of additional furniture distinguished them from surrounding houses. In particular, there was no bar in the modern sense of a fixed counter over which alcohol could be purchased and served.

Check out: Intoxicating spaces

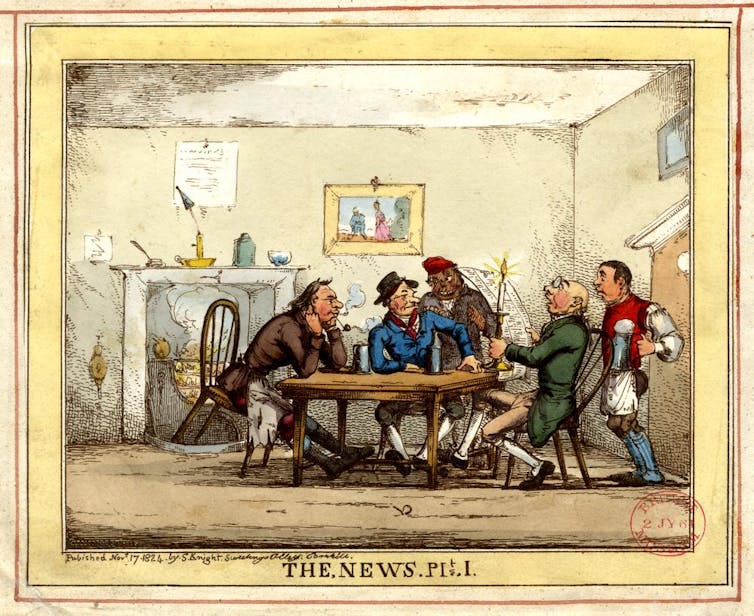

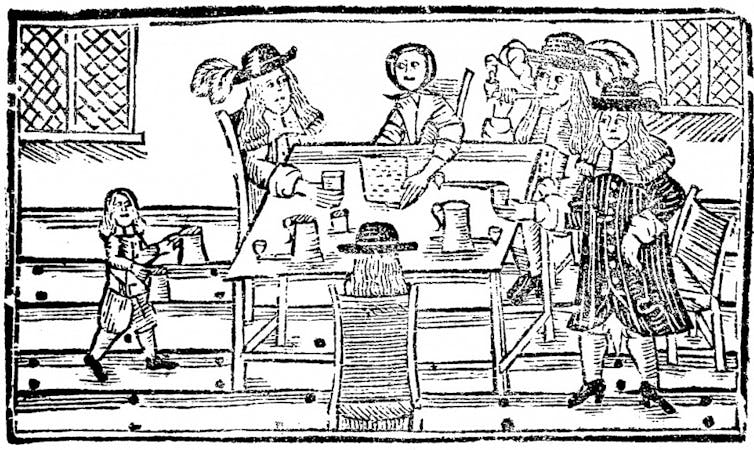

Instead, beverages were ferried directly to seated customers from barrels and bottles in cellars and store rooms by the host and, in larger establishments, drawers, pot-boys, tapsters and waiters. The layout of Margaret Bowker’s large Manchester alehouse in 1641 is typical: chairs, stools and tables were distributed across the hall, parlours, and chambers, while drink was stored in “hogsheads”, “barrels”, and “rundlets” in her cellar.

The bar as we know it didn’t emerge organically from these arrangements, but rather from the introduction of a new commodity in the 18th century: gin. Originally it was imported from the Netherlands and distilled in large quantities domestically from the later decades of the 17th century, but the emergence of a mass market for gin in the 1700s gave rise to the specialised gin or dram shop. Found mainly in London – especially in districts such as the East End and south of the river – an innovation of these establishments was a large counter that traversed their width.

Along with a lack of seating, this maximised serving and standing space and encouraged low-value but high-volume turnover from a predominantly poor clientele. The flamboyant gin palaces of the later 18th and early 19th century – described by caricaturist and temperance enthusiast George Cruikshank as “gaudy, gold be-plastered temples” – retained the bar, along with other features drawn from the retail sector such as plate-glass windows, gas lighting, elaborate wrought iron and mahogany fittings, and displays of bottles and glasses. While originally regarded as alien to local drinking cultures, by the 1830s these architectural elements started making their way into all English pubs, with the bar literally front and centre.

As architectural historian Mark Girouard has pointed out, the adoption of the bar was a “revolutionary innovation” – a “time-and-motion breakthrough” that transformed the relationship between customers and staff. It brought unprecedented efficiencies that were especially important in the expanding and industrialising cities of the early 1800s.

In particular, a fixed counter with taps, cocks and pumps connected to spirit casks and beer barrels was more efficient than employees scurrying between cellars, storerooms and drinking areas. This was especially the case for “off-sales” – customers purchasing drinks to take home – which had always been a large component of the drinks trade and still accounted for an estimated one-third of takings into the 19th century.

Posterity has paid little attention to the armies of service staff who kept the world of the tavern spinning on its axis before the age of the bar. But they are occasionally glimpsed in historical sources – such as Margaret Sephton, who was “drawing beer” at Widow Knee’s Chester alehouse in 1629, when she gave evidence about a theft of linen. While skilled – one tapster at a Chester tavern styled himself rather grandly in 1640 as a “drawer and sommelier of wine” – drink work was poorly paid. Staff were often paid in kind with food and lodgings and the work was usually undertaken by people who were young, poor, or new to the community.

The lack of a bar made the job especially challenging. It was physically demanding – in 1665 a young tapster at a Cheshire alehouse described how during her shift she was “called to and fro in the house and to other company, testifying to the constant back and forth. The fact that drinks were not poured in front of patrons made staff more vulnerable to accusations of adulteration and short measure – sometimes with good reason – and close physical proximity to customers when serving and collecting payment meant such disputes could more readily turn violent. For female employees, the absence of the insulating layer of material and space later provided by the bar meant they were much more exposed to sexual abuse from male patrons.

What can the historical record teach proprietors of any newly bar-less pubs? There are, of course, modern advantages such as apps and other digital tools – plus the example of European and North American establishments, where table service was never fully displaced. But there are practical lessons to be learned from the past all the same. Publicans today might streamline the range of drinks on offer and encourage the use of jugs for refills. Landlords could develop careful zoning for their staff – in larger alehouses and taverns tapsters were allocated specific booths and rooms. Most importantly they need to establish and enforce clear rules about behaviour towards staff – especially in terms of physical contact. Better to have premodern pubs than no pubs at all, after all.![]()

James Brown, Research Associate & Project Manager (UK), University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments