Spare Rib: 50 years since the groundbreaking feminist magazine first hit the streets – its legacy still inspires women

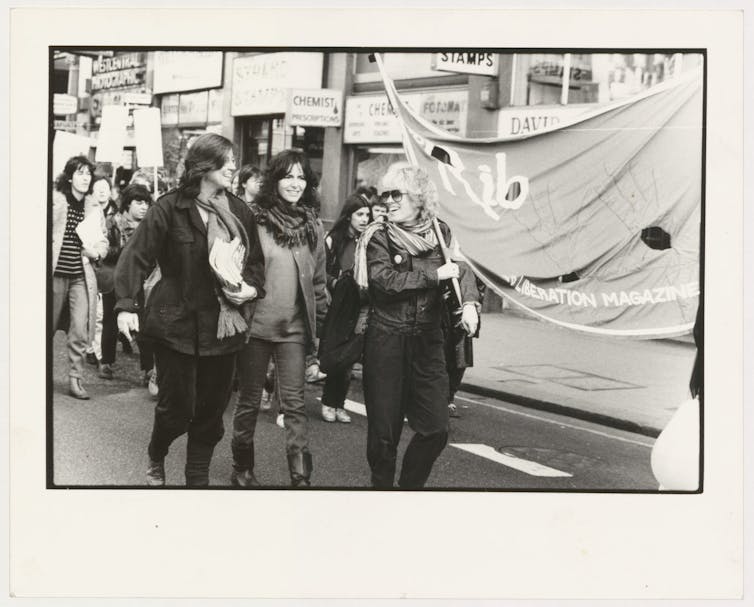

In the summer of 1972, the Women’s Liberation Movement was fighting hard, through rallies and marches, for social, sexual and reproductive liberation. The “second wave” of feminism was at its peak, gaining notoriety after a group threw flour bombs at the Miss World beauty pageant in 1970, highlighting the objectification of women. It hit the news once again in the UK in 1972 when a group of women night cleaners went on strike in London for better working conditions.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone at the time was on board with these women’s claims for equality and the British and American presses often caricatured them as humourless, hairy-legged, bra-burning, unsexed harpies who were set against marriage, families and femininity. To counter the noise of this sort of coverage came the groundbreaking feminist magazine Spare Rib.

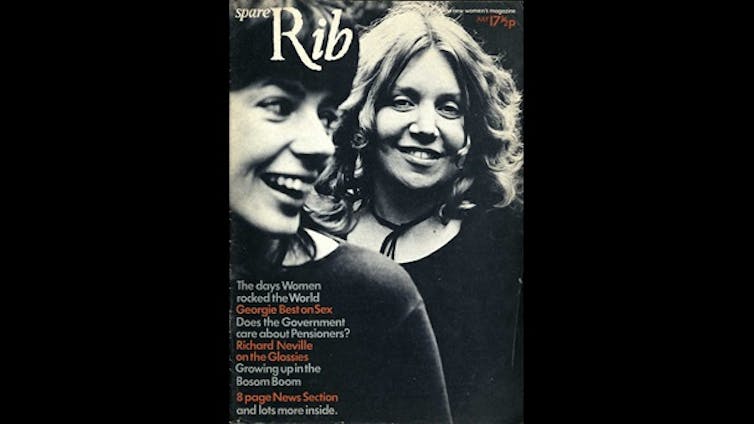

With witty coverage and incisive features, the magazine echoed the demands of the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM). The magazine supported campaigns and generally exposed women’s social and cultural experiences of sexism. Spare Rib did all this with captivating journalism and a great sense of humour. The magazine closed in 1993 due to commercial pressures. This year, we celebrate 50 years since its first issue and look back at the legacy it has left behind for feminist media.

A new kind of feminist magazine

The magazine’s founding editors, Rosie Boycott and Marsha Rowe, railed against the sexism and chauvinism of the underground, alternative press, where women were restricted to mundane tasks and excluded from editorial decision-making.

Spare Rib and women’s presses, such as Virago, forged a radically different approach to publishing. Female-led editorial boards enabled open debate of previously taboo subjects such as female orgasm and lesbianism long before these became mainstream concerns. Many feminist magazines operated as collectives and encouraged women to develop publishing skills in the male-dominated profession.

In format and content, Spare Rib crossed boundaries between magazines that focused on home, beauty and lifestyle, such as Woman’s Own, and more overtly political, grass-roots movement media, such as Shrew or Red Rag. In this way, it emphasised both the personal and the political sides of the feminist movement.

In its early days, Spare Rib partially emulated conventional women’s magazines by including articles about cookery, handcrafts and DIY – albeit with a feminist twist and a “can-do” attitude. But it was never conventional in its topics and opinion pieces.

Like Cosmopolitan, which launched the same year in the UK, Spare Rib never shied away from bringing women’s sexuality to the fore. But unlike Cosmopolitan, it also directly addressed sexism in Britain. Spare Rib’s “news pages” kept feminists informed and involved with current protests, updates and achievements. Its lively letter pages also encouraged heartfelt reader involvement.

Over two decades, Spare Rib worked relentlessly for social change, investigating and promoting awareness of serious topics concerning women’s mental and physical health. These ranged from women’s diverse sexuality, home life, domestic abuse, equal pay, sexism in the workplace, female genital mutilation and the refuge movement (which provided safe shelter for battered women) and more. Heightened awareness today of these issues owes much to the campaigning work of those second-wave feminist magazines.

The magazine had a complex relationship with consumerism, navigating an uneasy path between needing advertising revenue but rejecting the sexism of the industry at the time. They did this by trying to advertise ethical products only alongside subscription ads and its own-brand products, such as the Spare Rib diary.

But it struggled to sustain itself with diminishing ad sales and subscriptions. Alongside this, distribution problems and arguments over the direction of the magazine led to its demise and eventual closure in 1993.

The difficulties of representing a movement

From as early as 1982, Spare Rib faced criticism that it was too white, middle-class and London-centric. In 1984, a crisis within the editorial collective revealed that many – including women of colour, Jewish women, Irish women, lesbians and more – felt that Spare Rib, alongside much British feminism, didn’t speak for them or address their particular concerns.

While Spare Rib grappled with diverse identity politics, other feminist magazines spoke directly to different groups. Women’s Voice, founded through the Socialist Workers Party, focused on working-class women.

Mukti: Asian Women’s Magazine, was published by the Mukti collective in six languages and funded by London Camden Council. FOWAAD was a national newsletter for women of African and Asian descent. There were also local feminist publications, such as the Leeds Women’s Liberation Newsletter, which highlighted regional feminist concerns around the UK.

Spare Rib itself became much more international in its feminism too. Recent research on women’s activism around Britain has found that regional feminism and Spare Rib were more far-reaching in their perspective than previously thought.

Innovative, informative, contemporary and political, Spare Rib educated and politicised its readers, galvanising and encouraging feminism in Britain. More than this, it gave women a voice and forum to tell their life stories, enabling them to raise awareness of a myriad of issues.

The self-expression and persuasive writing of Spare Rib have their legacy in feminist media today such as the F-Word, feminist websites such as Everyday Sexism, and online blogs like The Vagenda. Because of its standing in feminist history, Spare Rib has become a touchstone for later feminist magazines, and there was even an attempt in 2013 by Guardian journalist Charlotte Raven to revive Spare Rib itself. Sadly this came to nothing, but the legacy of Spare Rib continues to this day.![]()

Laurel Forster, Reader in Cultural History, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments