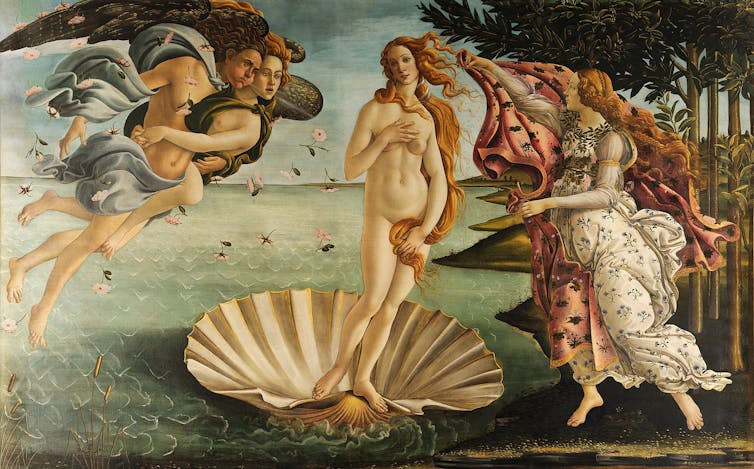

Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus resides within the Uffizi gallery in Florence, Italy. It is believed to have been painted in the mid-1480s and as such is classed as being in the public domain, free from copyright around the world. However, in early July the Uffizi set its lawyers on the website Pornhub, sending the company a strongly worded letter threatening legal action over the unwelcome use of The Birth of Venus along with several of Uffizi’s other masterpieces.

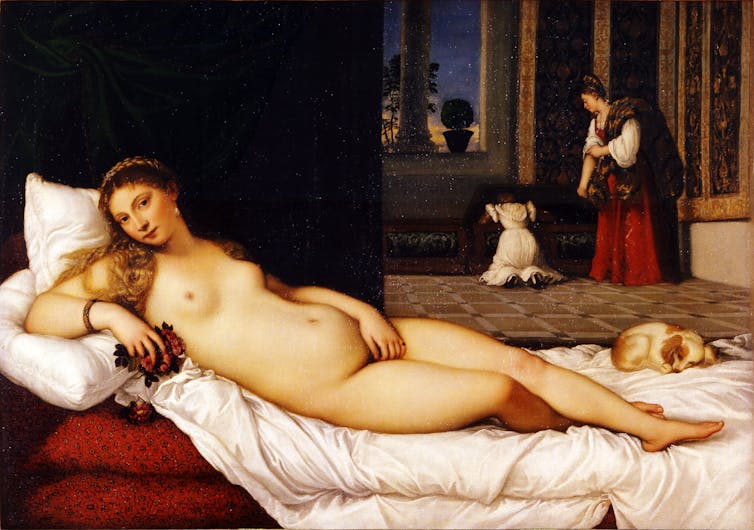

This came in response to the pornography platform’s launch of an online guide to the nude or erotic aspects of artworks in well-known galleries and museums around the world, such as the National Gallery in London, the Museo del Prado in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris and the Uffizi Gallery. Particularly controversial has been Pornhub’s turning of classic artworks into pornographic videos.

It seems the letter has produced its desired effect as Pornhub has subsequently removed any references and artworks pertaining to the Uffizi. But how was it able to create this legal pressure over something in the public domain?

Protection of cultural heritage

The Uffizi has likely invoked rules within the Italian Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code. This law empowers possessors of cultural heritage artefacts to prohibit their commercial exploitation, even where the latter have been created centuries ago.

Italian law strongly protects its heritage. The definition of cultural heritage itself under Italian law is broad: any works which “are of artistic, historical, archaeological and ethno-anthropological interest”. So, if you want to use the image of the Colosseum in your pizza delivery commercial, you may need to pay (at central or local level) a licence fee. An action can be taken to stop any unwelcome or controversial use of the image, for example in a context like porn websites.

In 2017, a court in Florence ordered a ticket agency to stop using the image of Michelangelo’s David on its brochures and website. In the same year, another court in Palermo condemned a bank that had used pictures of the local Teatro Massimo in their advertising campaign. Indeed, in Italy entities which own cultural artefacts can oppose any commercial use of such artefacts. Yet, whether this may happen in other countries remains doubtful.

The issue is not only legal. It also political. In 2014, the Italian culture secretary, Dario Franceschini, strongly protested against US arms engineering company ArmaLite which disseminated ads depicting the David carrying a rifle. Franceschini claimed that the Armed David jeopardised the honour and artistic value of Buonarotti’s work.

Copyright and the public domain

Museum and galleries can also rely on copyright to restrict the use of pictures of public domain pieces within their collection, or anyway charge for such use. Several of them actually do that – for example by declaring that their photographs of old paintings are subject to copyright and cannot be used without paying a fee.

But is that fair? One may note that giving custodians of old artefacts a monopoly over those pictures means to artificially monopolise the underlying works, which should instead belong to the public and be available for anyone to use or reuse it.

There is also an issue of originality. Copyright law only protects original works of authorship. While the originality requirement is interpreted generously in most countries, a threshold does exist. In a US case in the late 90s, Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp, it was held that exact photographic copies of public domain images could not be protected by copyright because the copies weren’t original enough.

Yet, it could be counter-argued that these photographs are not iPhone pics taken by holidaymakers.

Time, labour and skills are needed to move a painting from the gallery or museum to the studio. The photographer must be skilled, good cameras need to be used which avoid glare, and ensure careful light meter readings and faithful colours.

This is an investment – the argument goes - that must be legally protected, for example via a no-photo policy. Indeed, there are economic interests at stake. Take the Uffizi again. It is one of the most visited museums in Italy, and in 2019 around €1 million (£850,000) in revenue came from the sale of photographs of its collection.

While pictures of public domain works are not the focus in the case involving Pornhub, the Uffizi regularly relies on copyright to extract economic profits out of those pictures.

Access to culture

There is also an access to culture angle. Laws which consider pictures of paintings created centuries ago as deserving copyright protection frustrates the most important principle of copyright regimes themselves: namely, that after a specific period of time everyone should be able to use, and build upon, artworks that have fallen into the public domain.

There is the need for a wide category of people to access high quality and faithful representations of public domain works. This is the case of an art university professor showing the pic of an old artwork in class or an art historian publishing the photo in her book. Creators who want to incorporate, build on and reinterpret public domain works should be able to do so on free speech grounds.

Restricting the ability to use these pictures by tampering with copyright law is risky. Yet, it is one thing to rely on criminal law to stop crimes and another to turn copyright upside down so as to indirectly be able to monopolise artistic works, which are simply too old to be protected.![]()

Enrico Bonadio, Reader in Intellectual Property Law, City, University of London and Magali Contardi, PhD Candidate, Intellectual Property Law, Universidad de Alicante

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments