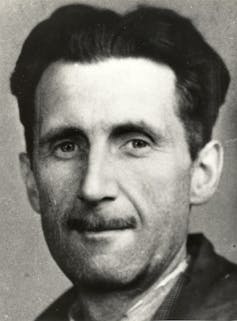

MC Duke: a pioneering British rapper more people should know about

MC Duke (Kashif Adham) was a key figure in the development of hip-hop in Britain in the late 80s. When he died in April, British rap lost a giant. From the East End of London, Duke strengthened the evolution of the genre in the UK by relating directly to US hip-hop and an emerging British rap identity through his lyrics and visual style.

At the time of MC Duke’s arrival on the rap scene, British hip-hop was transitioning from the electro-based sound by London artists such as DSM, Three Wize Men and Family Quest, to a more sample-based style, much like the sounds of US artists Eric B. and Rakim and Biz Markie.

In this transition, Duke emerged as the frontrunner in this new generation due to his embrace of hip-hop’s visual tropes as much as his sound.

His first release, Jus-Dis landed in 1987 on Hard As Hell! Rap’s Next Generation, a compilation released on Music Of Life – a staple label for homegrown British talent. Jus-Dis presents Duke’s battle rap attitude through the diss track – a concept where the song’s narrative attacks another party.

His lyrics and wordplay on the song title present social commentary on Britain and its legal system: “There ain’t no law, there’s only jus-dis.” Duke also brought the idea of the diss to live audiences throughout the UK by accelerating the dispute with Overlord X, another pioneering British rapper, as part of his stage routine.

His first proper single release, Miracles, the next year, visually presented MC Duke and his DJ, DJ Leader 1, for the first time to audiences. The record sleeve depicts Duke donning a bright red goose jacket, a black leather cap, Cazal-style shades, gold rope chain and a name belt buckle – all highly sought-after attire in hip-hop fashion.

These fashion choices linked the US image of rap with an emerging British one. In the US, rap pioneers T La Rock and Kool Moe Dee had previously used similar accessories on album covers to denote a sense of identity. In the UK, graffiti writers and breakdancers particularly were sporting name belt buckles.

Miracles heavily samples The Jackson Sister’s I Believe In Miracles, which was a mainstay of the rare groove scene that developed in London during the early 80s. With the inclusion of vocal samples from Run-D.M.C.’s Run’s House and Public Enemy’s Bring The Noise, Miracles starts to bring together a transatlantic idea of hip-hop.

Got To Get Your Own based on Reuben Wilson’s song of the same name and MC Duke’s follow-up single, I’m Riffin (English Rasta) heavily samples Funky Like A Train (link) by Equals, again a core record from many rare groove playlists.

The introduction to I’m Riffin (English Rasta) is sampled from the powerful speech by American civil rights leader Jesse Jackson from Introduction (Complete). This immediately frames MC Duke’s lyrics with a sense of Black identity and history, as he raps: “Known to speak about men of freedom, Look for books on King and read ‘em”.

Duke returns the narrative to a sense of the everyman: “We cover and smother another brother, Throw him away just like a used rubber,” twice referring to the system as at the heart of Black-on-Black crime.

Duke’s “English Rasta” pseudonym is also a comment on Jamaican culture in Britain, in particular the second generation who grew up through an evolving Black British identity.

M.C. Duke and DJ Leader 1’s debut album Organised Rhyme challenges the British class system, the aristocracy, colonialism and imperialism. Duke claims their associated visual tropes and brings them into a rap frame fusing tweed suits, hunting boots, Bentley cars and stately homes with the African medallions and chunky gold jewellery of hip-hop.

In 1990, Duke countered the conventions of the British aristocracy as a producer and performer on the album The Royal Family, a collective of artists from the Music Of Life camp, including the likes of Lady Tame and Doc Savage. This album resonates with US label-related collectives such as Marley Marl’s Juice Crew and The 45 King’s Flavor Unit. Again, this enforces the transatlantic approach to hip-hop that Duke maintained.

Duke’s work ensured British fans felt homegrown rap was becoming closer to US artists like Eric B. & Rakim and Public Enemy. Additionally, his music laid the foundation for future solo British rappers as diverse as Ty, Dizzee Rascal and Stormzy.

As well as being a forerunner in British hip-hop, Duke worked across dance genres and influenced many jungle, drum ‘n’ bass and grime emcees. As Jumpin Jack Frost (the DJ behind the seminal jungle track Burial, which he released under the alias Leviticus) attested: “Duke was a true trailblazer who was one of the first UK MCs with a major record deal … His legacy will be remembered as someone who helped to shape UK MCs from jungle to grime we all owe MC Duke a lot.”

MC Duke bridged the gap between US hip-hop history and set a new British trajectory for rap. His work should serve as a critical signpost for British rap audiences.![]()

Adam de Paor-Evans, Research Lead at Rhythm Obscura / Lecturer in the School of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Plymouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.