50 years of Linder’s art – feminism, punk and the power of plants

Currently on show at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, Linder’s retrospective Danger Came Smiling showcases half a century of trailblazing art. The exhibition delves into her fascination with plants, inviting the viewer to see beyond traditional notions of gender and sexuality.

For the Liverpool-born artist, there is enchantment in creating imaginary worlds, generating new meanings and inviting others in. Turning toward botanical themes marks a compelling evolution in Linder’s art practice. This new twist fuses a more glamorous side of her punk-feminist roots with symbolic power of the natural world.

Her fascination with plants isn’t just visual, it’s conceptual. In Danger Came Smiling she uses botanical imagery to examine how nature has historically been feminised, controlled and aestheticised, as she explores plant reproduction, horticultural histories and the cultural symbolism associated with flowers.

The Goddess Who Lives in the Mind (2020) features a gigantic lily with stamens protruding from a glamorous woman’s body, while Double Cross Hybrid (2013) reveals an enormous rose blooming out of a woman’s stomach – a monstrous “other” taken away from the domestic space, dressed in botanical themes.

A living critique of gendered power structures – the way access to power, privilege and resources is disproportionately dominated by men – the exhibition is rooted in the organic and the ephemeral, with echoes of her earlier subversive photomontages.

Linder is best known for this disruptive technique – cutting and pasting images from disparate sources to create new, often shocking visual narratives. Her work embodies the radical spirit of early 20th-century European Dada and Surrealists such as Hannah Höch, George Grosz and Dora Maar who pioneered the method, amalgamating images from popular media, magazines and photography into political and satirical statements.

Her critique of the commodification of the female body also draws inspiration from feminist artists such as Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann and Martha Rosler. Here, her photomontages are like jigsaw configurations that blur the boundaries between art, ecology and mythology.

Linder’s outdoor performance A Kind of Glamour About Me was staged to great effect this summer at the opening night of the Edinburgh Art Festival. A dazzling, genre-defying spectacle, it fused Holly Blakey’s visceral choreography, Maxwell Sterling’s haunting soundscapes and Ashish Gupta’s flamboyant fashion. Showcasing an eerie synthesis of body and nature, it turned the Royal Botanic Garden into a site of transformation and storytelling. Here visitors can enjoy it as a video installation.

An improvised take on the myth of Myrrha – the Greek mythological figure who was turned into a myrrh tree after having sex with her father – three dancers in exquisite costumes appear as shifting identities, with one eventually merging into a tree for protection.

Linder draws inspiration from the mythical symbolism of plants. The word glamour in her work comes from the Scots word glamer, which means a magic spell – witches in 16th-century Scotland were hanged for casting “glamer”. Traces of Linder’s photomontage style spill over into the verdant green of the gardens – gigantic lips appear out of nowhere, like a haunting Cheshire cat’s smile.

Linder reclaims women in history and mythology as forbears and heroines. Just like her photomontages, whether in live performance or in video, they are made of parts and fragments that come together in ethereal improvisations.

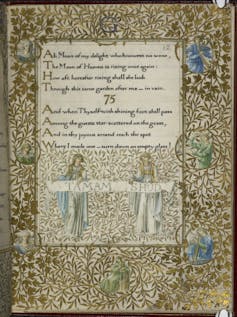

Her eerie video work Bower of Bliss (2018) is inspired by the detention of Mary Queen of Scots at Chatsworth House in the late 16th century (Linder was in residence there in 2017). In the video, Mary and her custodian Bess of Hardwick are dressed in lavish, colourful costumes designed by Louise Gray. They move to a Maxwell Sterling composition that signals the pleasures and boredom of confinement through clinging, holding and posing. Here we see fabrication mixed with history, witch with knight, warden with prisoner.

Featuring themes of female empowerment and enchantment with nature, Linder’s signature tableaux vivants (living pictures), reveal performers’ dramatically made-up eyes and lips covered with herbs and flowers from the kitchen garden.

Bower of Bliss refers to an enchanted garden from Edmund Spence’s poem The Faerie Queene. The work was originally recreated for Art on the Underground as a billboard at Southwark station in 2018, featuring women who worked on London Underground and performed in the dance work created from it.

Linder’s newer digital works appear to depart from the DIY-rebellion aesthetic of the radical punk era of the 1970s and early 1980s (such as her iconic Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict album cover). Cut-and-paste aggression, visual noise, and an anti-polish vibe were reactions to her life story at the time, when she was fighting the feminist cause.

Newer works acknowledge the limitations of punk’s visual language and Linder’s desire to move beyond shock value toward more ritualistic, poetic and nature-infused forms of resistance. She invites us to see plants not as decorative or scientific specimens, but as symbols of survival, sensuality and subversion. These works recycle her artistic technique of combining imagery from domestic or fashion magazines with pornography and other archival material featuring petals, plants or marine life.

Her botanical turn is both a continuation of her feminist sensibility and a new way of engaging with the world, through the slow, radical language of nature. Cleansing the wounds of women represented in her works as well as her own, it leans into the language of plants as a profoundly healing experience.

It is a joy to watch this groundbreaking icon evolve her practice, transformed from an angry young rebel to an accomplished multimedia artist. At the age of 71, Linder continues to challenge societal norms while embracing the beauty and complexity of identity, cementing her legacy as a trailblazer in contemporary art.

Danger Came Smiling is on at Inverleigh House, the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, until October 19, and then transfers to the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea, in November 2025.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.![]()

Katarzyna Kosmala, Chair in Culture Media and Visual Arts, University of the West of Scotland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.